Mike Cronk was sitting half-naked on a street corner, hands covered in blood, when the TV news reporter approached. The 48-year-old, who had used his shirt to try to plug a bullet wound in his friend’s chest, recounted in a live interview how a young man he did not know had just died in his arms.

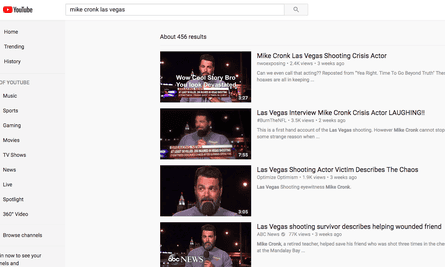

Cronk’s story of surviving the worst mass shooting in modern US history went viral, but many people online weren’t calling him a hero. On YouTube, dozens of videos, viewed by hundreds of thousands of people, claimed Cronk was an actor hired to play the part of a victim in the Las Vegas mass shooting on 1 October.

Conspiracy theorists harassed him on Facebook, sending messages like “How much did they pay you?” and “How does it feel to be part of a hoax?” The claims multiplied and soon YouTube’s algorithm began actively promoting the conspiracy theory.

Two months later, Cronk’s online reputation appears damaged beyond repair. Type “Mike Cronk” into Google and YouTube, and the sites automatically suggest searches for “actor” and “fake”, leading to popular videos claiming he and his wounded friend were performers and that the Mandalay Bay tragedy that killed 58 people never happened.

“It’s awful that we have to go through what we did and then you have a whole new level of attacks on you and who you are,” said Cronk, a retired teacher. “I don’t want negative stuff associated with my name, but how do we stop that?”

As record-breaking mass shootings have become a ritual of life in the US, survivors and victims’ families across the country have increasingly faced an onslaught of social media abuse and viral slander. Bullying from the ugliest corners of the internet overwhelms the grief-stricken as they struggle to cope with the greatest horror they’ve ever experienced.

The cycles of hoaxer harassment are now as predictable as mass shootings. And yet those with the most power to stop the spread of conspiracy theories have done little to address victims’ cries for help.

‘Like a swarm of locusts’

Alison Parker was a television reporter who was shot dead by a disturbed former colleague during a routine morning broadcast.

Her father, Andy Parker, first encountered the conspiracy theorists who believed her murder was a hoax on his YouTube page. Before the shooting, he had uploaded a selection of videos appropriate for a 62-year-old Virginia dad: kayaking footage, recordings of Alison’s dance recital, old commercials in which he appeared as a young actor in New York.

Afterwards, strangers online had seized on his decades-old acting career as proof that his daughter’s August 2015 shooting had been staged and that Andy Parker had supposedly been hired to act the role of a grieving father.

Commenters said he was part of a plot to trick the public into supporting gun control. “It was like a swarm of locusts,” he recalled.

Andy quickly made his page private – but the hoax theorists did not go away.

This spring, nearly two years after Alison’s death, as Andy’s wife, Barbara, was searching online for something related to the foundation they had set up to honor their daughter’s memory, she found something else. “The second thing that opened up on Google was a YouTube video that the foundation is just a scam for Andy Parker to make money, a complete hoax.”

“I don’t care what they say about me,” Andy said, “but leave the foundation alone. Leave my daughter alone.”

It didn’t take much searching for the father to find other YouTube videos. “There were pages, endless pages of stuff.” Posts about Alison’s murder that analyzed footage and photographs, asking why there was no visible blood from her being shot. Others claimed Alison was still alive, that she had had plastic surgery to change her appearance and was now living in Israel.

Hoaxers said Andy’s “acting” in TV interviews was subpar. One video of the choked-up father talking about Alison had a caption floating above his forehead: “No tears!”

More recently, Cori Langdon, a Las Vegas taxi driver who picked up survivors of the October massacre, became one of the prime targets for conspiracy theorists after she posted video from the scene. Her footage was stolen and republished across the internet and used as “proof” of a number of debunked claims, including the rumor that there was a second shooter.

Violent threats quickly filled Langdon’s inbox and populated the comment sections on YouTube and Facebook. People called her “queen of cunts” and “one of the dumbest fucking idiots”.Others said she was “braindead”, “FAKE AS FUCK” and “fucking stupid!”, with one writing: “They should bring this cab driver in for questioning.”

“I was a basket case, it was so overwhelming,” she said, recounting the first week after the shooting.

One conspiracy theory surrounding Langdon was that she had been killed after the massacre as part of a cover-up. She tried to make light of it, hoping that if the trolls believed she were dead, they would leave her alone. But she recalled one friend telling her: “Somebody might try to kill you, Cori, so they can prove their conspiracy theories.”

Meanwhile, Braden Matejka, who survived a gunshot to the head in Vegas, received such a high volume of online attacks and death threats from people calling him an “actor” that he had to close his Facebook account. One message said: “I hope someone truly shoots you.”

Lenny Pozner, whose six-year-old son, Noah, was killed in the Sandy Hook elementary school shooting in December 2012, has faced some of the most vicious abuse and threats. This year, a woman was sentenced to prison for sending him violent threats, telling him on multiple occasions that death was coming “real soon”.

Rob McIntosh, who survived a gunshot to the chest in Las Vegas, said he could not figure out the motives of anonymous users online accusing victims like him of lying: “I don’t know what the driving force behind people being like that is. I don’t understand.”

Why people believe

There is no easy way to change the mind of a conspiracy theorist.

Colleen Seifert, a University of Michigan psychology professor, said people were inclined to trust content they viewed on YouTube and might be drawn to mass shooting conspiracy theories simply because the tragedies were so implausible and frightening to them.

“The idea that you could be innocently going to a concert and could be shot – you don’t want to believe that’s true. You’re protecting your own feeling of security and safety.”

It’s unclear how much belief in conspiracy theories has changed over time. A study based on reader letters sent to two major newspapers between 1890 and 2010 found the percentage stayed flat. But in recent years, conspiracy theories have begun to spread at much faster rates online, and many different kinds of people believe them, said Jan-Willem van Prooijen, a psychologist at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

“It was always assumed that this is just a small group of lunatics,” he said. “We now know, because of representative samples in various countries, that this is really very widespread.”

One recent survey suggested that more than half of Americans believe 9/11 conspiracy theories and that more than 40% support theories about alien encounters, global warming and John F Kennedy’s assassination. There is little research on the prevalence of the “crisis actor” theory – a belief that the government or other conspirators stage mass shootings – but the hoaxes now reliably populate social media within the first 24 hours of many shooting tragedies.

“It’s typically very hard to discredit a conspiracy theory,” Van Prooijen said. “Anything people say that goes against a conspiracy theory can be seen as a sign that you are a part of the conspiracy theory.”

When Langdon, the Vegas taxi driver, briefly took down her viral video from Facebook so she could remove identifying information about her passengers, some conspiracy theorists said it was proof that the FBI was trying to silence her and cover up the truth.

“I’m a mainstream media gal. I don’t think the government is after me,” she said. “It just makes me sick.”

It can be particularly upsetting to victims of conspiracy theories to discover that intelligent people – and even their own friends – believe hoaxes.

Langdon said she learned that a mutual friend was duped by the fake news that she was murdered: “It made me realize, even in my own circle of friends and people I work with, there are people with some crazy imaginations.”

Van Prooijen, a widely cited scholar on the subject, said one of his best friends was a conspiracy theorist. The professor hasn’t been able to change his views.

Another reason it is so hard to challenge conspiracy theories is the threats and bullying that now arise from simply speaking up. One shooting victim who was subjected to an aggressive harassment campaign did not want to do an interview for fear of inviting further abuse. Journalists and academics are often spammed with hundreds of messages when they write about the subject.

Some conspiracy theorists, however, change their tone when they are no longer writing to strangers on the internet.

Amy Hallas, a 44-year-old Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, woman, sent dozens of Facebook messages to the family of Braden Matejka, the Vegas victim who survived a gunshot in the head, accusing them of being liars and demanding proof of his injuries. Criticizing a GoFundMe page the family promoted to help raise funds for Matejka during his recovery, she called the family “beyond fake”, saying the victim was guilty of the “worst acting” she had ever seen.

In a phone call weeks later, Hallas claimed to the Guardian that she had never attacked the family and said she was just searching for answers.

Reminded that she had posted a meme on the Facebook page of Matejka’s brother that called the shooting victim a “lying cunt”, she said she didn’t remember and must have been caught up in the moment.

“I do feel bad. They are people, just like everybody else. Who am I to be calling anybody any kind of names?” she said. Asked if she regrets the attacks, she said: “I 100% do, and if I could apologize to them, I would.”

‘The burden shouldn’t be on us’

Andy Parker, whose daughter was murdered on live television, said he was not interested in understanding the psychology of those claiming a hoax. He said he just wanted the videos off of YouTube. His first step was calling a customer service hotline for Google, which owns YouTube. A young man from Manila, he remembered, explained how he could flag the videos to be taken down.

Parker began the work, but after marking about 10 videos, he said, he had to stop. There was footage of his daughter being killed all over the internet, but Parker had never wanted to see it himself. He had changed his YouTube settings so the videos would not automatically play, but even looking at their thumbnail images was too much. “I just couldn’t do it.”

The situation made him angry. Couldn’t a company as powerful as Google, he thought, provide a better way to combat conspiracy theorist harassment than asking the father of a murdered journalist to clean up YouTube himself?

The internet as we know it is founded on a simple legal principle: companies like YouTube and Twitter are not legally responsible for the content shared on their websites. But the tech corporations have been forced over the years to craft their own ethical standards, defining what kind of material is prohibited.

Still, the companies have not shifted far from their core objectives of maximizing engagement – prompting users to share and consume high volumes of content and enabling the instantaneous purchasing of ads without scrutiny.

The resulting algorithms are a perfect match for conspiracy theorists.

Some grieving parents have turned the grim task of tracking down hoax theory videos into a daily job. In 2014, Pozner, whose child was killed in the Sandy Hook massacre, founded the Honr Network, an organization dedicated to holding conspiracy theorists accountable. Hundreds of volunteers now help monitor the offensive content online.

With YouTube, Pozner uses different tools to argue that videos should be taken down: invasion of privacy, harassment and, in some cases, copyright infringement.

Often, it feels like he’s arguing with a robot – one that makes arbitrary decisions. Sometimes, the flagging process gets results. Other times the videos remain. The whole system, Pozner said, was frustratingly opaque.

“If I’ll report something for privacy, they’ll [sometimes] say: ‘We’ve decided not to take any action on this.’ Who do you appeal to, who do you contact, who do you pick up the phone and call?”

Parker talked to Pozner about his work, and Honr began flagging the Alison Parker hoax videos. But the conversation only reinforced Parker’s frustration with Google.

“I am so grateful to these folks that are doing this … but the problem is, to me, we shouldn’t have to be doing this piecemeal,” Parker said. “It’s like trying to kill roaches with a fly swatter. You kill a couple and a bunch of them come back. What we’re doing is demanding that they be responsible corporate citizens.”

Parker said YouTube should pay a team of humans to proactively remove content: “The burden shouldn’t be on us to prove that this content is bad … They’re not acting like a human company.”

Parker finally had a call with Google executives in October to discuss the problem, and he said he was now more optimistic that the company would work closely with the Honr network to address harassment.

It’s true that it might not be a huge expense for Google to hire one person to deal with Sandy Hook and similar hoax theory videos, said David Karger, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology computer scientist, who researches online harassment. But, he said, “would they need to hire someone else to handle all the white supremacist harassment, and someone else to handle all the gender harassment? It’s an issue of scale.”

YouTube, however, has no policy against conspiracy or hoax theory videos in general. In the wake of concerns from Parker and Pozner earlier this year, it clarified internally that hoax theory videos that targeted the victims or family members of public acts of violence would count as harassment, and could be taken down.

“Our hearts go out to the families who have suffered these incredibly tragic losses,” a YouTube spokesperson said in an email. “We recognize the challenging issues raised by the victims’ families, and that is why we updated the application of our harassment policy last summer. As a result, we have removed hundreds of these videos as they have been flagged to us and we will continue to do so.”

Struggling to move on

Cronk, the Vegas survivor and target of “crisis actor” hoaxes, said he tried to ignore the slander and attacks and focus on moving forward. He said he felt an obligation to live his life to the fullest, considering how lucky he was to survive.

“I’m not going to let it define who I am,” he said.

YouTube and Google, however, appear to have other plans for him. After the Guardian sent a number of videos targeting Cronk to company spokespeople, several were removed. Some of the worst ones, however, remained on the site.

“They are a business. In my mind, if people can slander people and they are allowing this kind of stuff there … they should absolutely be held responsible,” Cronk said.

One video that YouTube did not remove picks apart every comment and expression in one of his first television interviews as signs of his bad acting skills. In the video, titled “Las Vegas Hero Eyewitness or Actor???”, the narrator viciously mocks Cronk for appearing to smile in the interview.

“Yeah, Mike Cronk, and I’m totally sure that’s your real name too, wink wink. It was so horrific, so horrific that you had to smirk and smile on camera as you duped us with delight,” the narrator shouts. “Huh, silly boy!”

Despite multiple inquiries from the Guardian over several weeks, YouTube still suggests that Mike Cronk is a “crisis actor” in its search bar. The “Eyewitness or Actor?” video, viewed by more than 15,000 people, continues to be one of the top search results.