Why Many White Men Love Trump’s Coronavirus Response

More than 80 percent of Republicans think the president is doing a great job with the pandemic. Here’s why.

Kurtis, a young accountant in McKinney, Texas, likes the thing that many people hate about Donald Trump: that the president has left the pandemic response almost entirely up to local officials.

“He left it up to each state to make their own decision on how they wanted to proceed,” Kurtis told me recently. Most experts think the absence of a national strategy for tackling the coronavirus has been a disaster. But Kurtis argues that North Dakota, for example, shouldn’t have to follow the same rules as New York City. Kurtis voted for Trump in 2016, and he plans to do so again this year.

Some 82 percent of Republicans approve of Trump’s coronavirus response—a higher percentage than before the president was diagnosed with the virus. This is despite the fact that more than 220,000 Americans have died, and virtually every public-health expert, including those who have worked for Republican administrations, says the president has performed abysmally.

Experts offer a few different explanations for the spell that Trump has cast over his supporters. The simplest is that Trump voters like Trump, and as is often the case with people we like, he can do no wrong in their eyes. “We might just as easily ask why Trump opponents think he is doing a horrible job with the pandemic,” says Richard Harris, a political scientist at Rutgers University.

In academic terms, this is called “my-side bias”—objective reality looks different through the lens of your home team. (Sometimes literally: A famous 1954 psychology study found that undergraduates at Dartmouth and Princeton Universities had completely different perceptions of a football game played between the rival schools.) In fact, this tendency to approve of one’s own side might become self-reinforcing. If someone doesn’t support Trump and all that he does, they might stop considering themselves a Republican, and thus stop showing up as one in surveys, says Robb Willer, a sociologist at Stanford University.

Other wrinkles of our current political moment could further explain why so many Trump supporters approve of the president’s pandemic response. Katherine Cramer, a political scientist at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, says the most consistent theme on the right-wing talk-radio shows she’s been listening to is a desire to trust people to make their own decisions, rather than trusting the government to make decisions for people. Shana Kushner Gadarian, a political scientist at Syracuse University, pointed out that understanding the failures of Trump’s pandemic response might require intimate knowledge of other countries’ public-health systems—a tall order for the average person.

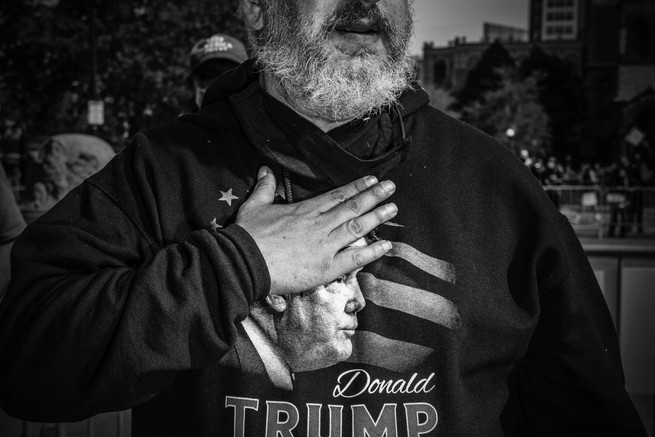

But another prominent scholar of the American right believes Trump support among men, in particular, is rooted in something more psychological. Many white men feel that their gender and race have been vilified, says the sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild. Their economic prospects are bad, and American culture tells them that their gender is too. So they’ve turned to Trump as a type of folk hero, one who can restore their sense of former glory. Exposing themselves and others to the coronavirus is part of that heroism.

Or as Kurtis told me when I asked him how he felt about Trump getting the coronavirus, “Trump’s willing to accept that risk to win for the American people. And Joe Biden is sitting in his basement.”

T

his hero theory of Trump is a continuation of Hochschild’s earlier work. A professor at UC Berkeley, Hochschild soared to the best-seller lists with her 2016 book Strangers in Their Own Land, which came out before the election but proved timely in its focus on the minds of Trump voters.

For the book, Hochschild interviews an array of characters across Louisiana in an attempt to unearth what she calls their “deep story”: the emotional, feels-as-if truth of their lives.

Hochschild describes her subjects’ deep story in a metaphor of a long line of Americans standing on a hill, waiting to get over the top, to the American dream. But as they stand there, tired and eager, they see that certain people are cutting the line in front of them. Women, African Americans, and immigrants are getting ahead, boosted by the government and its affirmative-action programs. As Hochschild writes, they feel “your money is running through a liberal sympathy sieve you don’t control or agree with.”

Many white men, in particular, feel “shoved back in line,” she writes. Unable to draw confidence from their wealth, which is in many cases nonexistent, or their jobs, which are steadily being moved offshore, they turn to their pride in being American. “Anyone who criticizes America—well, they’re criticizing you,” she writes.

Trump, meanwhile, has allowed his male supporters “to feel like a good moral American and to feel superior to those they considered ‘other’ or beneath them,” she writes. Trump might not always represent his supporters’ economic self-interest, but he feeds their emotional self-interest. Trump is, in essence, “the identity politics candidate for white men.”

For a new book, Hochschild is talking with people in eastern Kentucky, another heavily conservative area. One trend she’s noticed is local white men’s lost sense of pride, and how they turn to Trump to restore it. To them, Trump seems to say, “I’m taking the government back and having it serve you,” she told me. “I’m your rescuer.”

In Strangers, some of the Louisianans Hochschild interviewed were upset that women were competing for men’s jobs and that the federal government “wasn’t on the side of men being manly.” Some of her male Kentucky interviewees, especially those who have a family history in coal, feel even more strongly that men’s rightful place in the world is slipping away.

Men in this community, she told me, “are starved for a sense of heroism. They don’t feel good about themselves. They feel like they haven’t done as well as their fathers, that they’re on a downward slope.” Coal jobs have evaporated, and liberals, they feel, are making enemies of white men. “Their source of heroism, of status, is humming; it’s fragile,” Hochschild says. This analysis comports with some polls of Trump voters. An Atlantic/PRRI poll conducted in 2016 found that Trump supporters were more likely than Hillary Clinton supporters to feel that society “punishes men just for acting like men.”

As far as their leader’s pandemic response, Hochschild’s Kentuckians feel that Trump is doing the best he can, and as good of a job as possible under the circumstances. Though her subjects are worried about catching COVID-19, many see it as one of the unfortunate but acceptable risks of life. Confronting the coronavirus is a way to show stoicism and to feel heroic again. “I’ve heard it said that ‘This is hitting older people, and I’m an older person, but it’s really important to get back to work, and I’ll take the hit,’” Hochschild said. Her subjects think they can handle the virus just like Trump handles everything. “He’s a two-hamburger-a-meal guy,” she said. “He’s kind of a bad boy, and they relate to that.”

This part of Trump resonated with Kurtis, who told me he likes that the president “comes off as a man. He doesn’t come off as weak.” Trump’s strength is a benefit in the foreign-policy arena, Kurtis feels.

Joe Biden doesn’t give these men the same sense of restored pride. They feel the Democratic nominee is a Trojan horse liberal women and minorities are using to advance their own interests. Biden doesn’t present himself as a defender of white men, and they don’t see him that way.

Hochschild sees her new work as an extension of the deep story she began probing in Strangers. In that book, her interview subjects found their guy in Trump. Now her interviewees are coming to realize their hero is surrounded by enemies. He’s battling evil forces such as the liberal media, the impeachment, the Democrats in Congress, and the lawyers who indicted his advisers. But Trump is fighting all of those enemies—the left, the deep state, the pandemic—and he’s fighting them for his constituents.

The final chapter of this story, she said, is Trump becoming an almost Christlike figure to these men. “‘Look how I suffer,’” is how Trump presents himself, Hochschild told me. “‘I am suffering for you.’ And they say, ‘Thank you.’”

I first met Kurtis in 2018, when I traveled to McKinney, my hometown, for research for my book about outsiders. I wanted to try to figure out why Californians were moving to the Dallas suburb. Before they relocated, Kurtis and Crystal had been living in Long Beach, paying $1,500 a month for an apartment the size of a bouncy castle. Kurtis found himself constantly at odds with his fellow Californians, who would yell at him for saying that he didn’t believe in global warming or that he was voting for Trump. “It’s like I couldn’t walk around with my ideas,” Kurtis told me for the book.

Now that he’s in McKinney, Kurtis feels much more at home. Kurtis and Crystal bought a $325,000 house with a wraparound deck. They don’t get sneered at for their views, and they don’t have to recycle anymore. Their extended families have since moved out from California to join them there.

And Kurtis wishes people would see the side of Trump that appeals to him: No apologies, what you see is what you get. Trump speaks the way people do at a barbecue, not at a dissertation defense. Sure, Kurtis reasons, the pandemic has killed a lot of people, but what was Trump supposed to do? Besides, the left called him a xenophobe for shutting down travel from China and for dubbing it the “China virus.”

Kurtis’s father recently caught COVID-19 at church, which Kurtis saw as just another example of people knowing the risks but doing what they feel they need to do anyway.

I asked Kurtis what he thought about Hochschild’s idea, that Trump supporters feel like white men are unfairly vilified these days.

Kurtis deflected a little. “I don’t think it has to do with being white,” he said. He has other reasons, such as taxes and a possible repeal of the Affordable Care Act, for supporting Trump.

At the same time, he was tired of “white men [being] looked at as the cause of everybody’s problems. I’m not gonna apologize that I’m white. I shouldn’t have to go around feeling like I have this great debt of reparations.”

It’s been good to have a leader like Trump, he added, who takes no B.S. and is there to kick ass. “I’m proud to be an American again,” Kurtis said.

Not all experts agree with Hochschild’s theory. Scott Winship, a sociologist and Director of Poverty Studies at the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute, says “it’s very questionable to explain overwhelming support among Republicans for Trump’s coronavirus response by pointing to whatever Hochschild’s white Kentuckians told her.” The income element, in particular, doesn’t hold up, he says: “Trump’s coalition in 2016 had higher incomes, on average, than the typical American.”

But other experts’ research generally supports Hochschild’s thesis. “People look down on us, and now is our time to win,” says Jonathan Metzl, a professor of sociology and medicine at Vanderbilt University, summarizing what he has found is the attitude of some Trump voters. Given that the pandemic has disproportionately killed people of color, some white Trump supporters may write it off as a “them problem, not an us problem,” he says.

Trump’s supposed heroism and sacrifice aren’t typically the reasons his supporters offer when asked about his pandemic performance. Other explanations—the freedom to not wear a mask, the corporate tax rate, disdain for the leftward shift in the Democratic party—are more easily quotable.

But the central wound remains: “Ban men” is a socially acceptable thing to say. And men who attend Trump’s rallies sometimes tell journalists that they’re willing to risk their lives to show up for Trump. “If I die, I die. We got to get this country moving,” these men tell reporters. Or: “If I catch COVID, that’s the consequences of my actions, so I’m willing to take that risk and have a good time today.” They’re bravely confronting COVID-19, just like the president.