“Matthew’s bed at home’s been empty for six months,” Isabelle Garnett says from the family house in south London as she tells me about her son. “I can’t walk by his bedroom.”

Since September 2015, 15-year-old Matthew Garnett – who has autism, ADHD and anxiety – has been held two hours’ drive away from his home in a secure mental health treatment unit in Woking, Surrey. Or as his mum puts it to me, “the equivalent of being left on an A&E trolley for six months”.

Isabelle and Robin, Matthew’s dad, struggling to cope as their son became violent towards them and knowing he needed help, agreed for Matthew to be detained at the unit while a suitable clinical placement within the NHS could be found. But six months later, Matthew is still there – and the family say he hasn’t been treated or even assessed. In desperation, Isabelle started a Change.org petition calling for her son to be given the treatment he needs (at time of writing it has near to 330,000 signatures). “I had to do something for Matthew because no one else will,” she says.

For the past fortnight, Isabelle’s been juggling her job working with children with learning disabilities, while “trying to keep things normal” for Matthew’s 12-year-old sister, and carrying out interviews with national media. In response to growing pressure, Alistair Burt, the community and social care minister, met the Garnetts on Tuesday. The family now finally have a confirmed date of next Tuesday for Matthew to move to St Andrew’s healthcare in Northampton – the specialist unit nearest to them. They had been told prior to the meeting there was no suitable facility in the whole of the south of England.

The reason Matthew has been unable to gain a place in Northampton sooner is that there are up to six young inpatients there waiting for a care package to allow them to go back to their own communities, which offers a worrying insight into the state of mental health services in this country.

What the Garnetts are enduring is not a tragic anomaly but represents failures that exist throughout the system – namely, flawed commissioning that means there are not enough specialist beds or local services. The result is restricted access to treatment while children in crisis are sent hundreds of miles from their families. There are 3,000 people with learning disabilities and/or autism – including 165 children – currently stuck in inpatient beds rather than living in their communities, according to the 2015 learning disability census. The National Autistic Society says that, with budgets squeezed, there is not enough incentive for councils to support children who are currently in places funded by the NHS.

Isabelle says since going public with Matthew’s case she’s been contacted by hundreds of other parents with “horror stories” – some of whom have had their children put in adult psychiatric wards. For Isabelle, as her and her family try to navigate the labyrinthine services, the problem is “systemic”. “There’s no joined-up thinking, no transparency. You go to one person, one part and it’s just ‘no, not my station’,’” she says. “No one’s accountable. No wants to talk about it … but what if it were their children?”

The Garnetts had been waiting for an assessment for Matthew since March 2015 – six months before he was sectioned. “If he’d have had the support in his local community, none of this would have happened,” Isabelle says. “It was totally avoidable.”

Held long-term in the unit, Matthew is regressing. His head has been shaved because he was tearing his hair out, and he has a fractured wrist after being pushed over by another inpatient while playing on the Nintendo Wii. Isabelle describes Matthew to me as having the body of a 15-year-old but in his mind – his emotions – “he’s a five- year-old”. He can’t share without help and, if he’s hurt, he can’t express that he’s in pain. Isabelle says it took 24 hours – and his wrist to start swelling – for staff to take him to A&E.

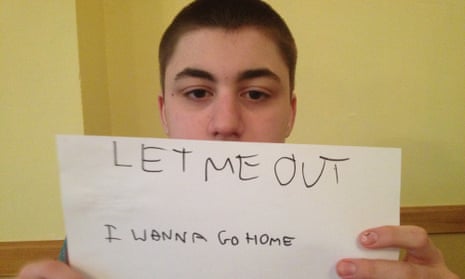

“They don’t know how to support him because they’re not trained for it,” she says. “I don’t even know what’s happening there.” She tells me, in his distress, Matthew has now ripped the cast off his wrist four times. “He says, ‘Mummy, am I prison?’ I want to break him out. But I can’t.”

The added cruelty is that, although all the family’s energy is going towards getting Matthew to a specialist centre, Isabelle is “terrified” of this happening. Because of the lack of local services, “the best place for him” – Northampton – will mean Matthew is further away from his mum than he is now. The next battle will be to get Matthew “back to his community and family that love him”. “This is not just Matthew,” she says. “The most vulnerable people in our society are being abused by the system. They’re children.” She pauses. “It doesn’t seem real. Like it shouldn’t be possible.”