The NSA collects and stores the phone records of millions of Americans. For thousands or millions of foreigners, it collects far more information than that, from the servers of US internet companies, computer networks, and more.

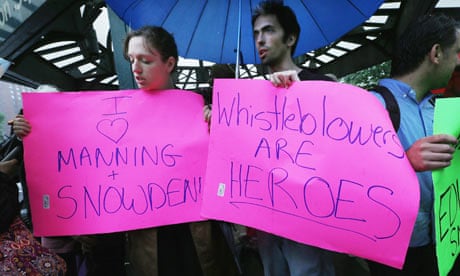

This much we know thanks to an unprecedented series of leaks from a 29-year-old security contractor: Edward Snowden. But the logic behind such mass surveillance, set out in his interviews, is in many ways as significant as the content of the leaked documents.

In a world where mass collection and storage of data gets easier every year, the nature of intelligence gathering changes. Snowden sets forth that the easiest way for intelligence services to operate is to collect as much data as possible, in case it's useful later.

In the case of phone records – who you call, when, for how long, but not the contents of the messages – that means collecting data on every customer of the networks, which then sits unexamined until there's a reason to look for a particular individual.

For the intelligence agencies, this avoids a frustration: when the NSA want to know more about a person, they can get the appropriate authorisation (for a US citizen, a secret court order; for foreigners, far less) and obtain their history, their associates, and their location from the data.

This prevents a previous frustration: by the time the NSA or intelligence bodies identified a suspect, their previous phone data (and more) had already been wiped. Mass surveillance and storage solves a real problem.

So too, of course, would a camera in every home; a bug in every computer. The question becomes: how much is too much?

When it comes to metadata, the defences are simple: the information collected is basic; your data almost certainly won't ever be looked at; and even if it is, unless you're a terrorist, it'll be completely innocuous.

None are necessarily that satisfying. One example that's been cited for the significance of metadata runs like this. Location records obtained from phones show the following people have been at a certain address:

Person A made a short visit, and then a few days later returned for four hours.

Person B spends eight hours at the address, on a Saturday.

Person C spends 10 hours at the address each day.

Person D visits for a short period, weekly.

In this hypothetical, the address is an abortion clinic. A has had a consultation followed by an abortion. B works at the clinic, C is a protester, and D is a trans person who needs to visit regularly for hormones.

Even a single piece of basic location detail can reveal some of the most sensitive secrets a person may have. The affair of the former head of the CIA, General David Petraeus, was revealed through email metadata. Metadata is also the "signature" of signature strikes – enough information to authorise a fatal drone strike. Metadata matters.

What might be found within yours? It might not take much for the NSA to seek an order to pull up your information: a misdialled call from an overseas terror suspect; a misfiring algorithm suggesting you're acting oddly; an acquaintance from 10 years ago who's now up to something shady.

The intelligence services are working to get information to prevent potential atrocities. That's a serious task, and so collection is important. What could be in your records that help that?

Phone calls with a pot dealer, evidence of file sharing, or more, are all things that generally intelligence agencies would ignore. But if you're caught in the dragnet, even wrongly, they could be applied as pressure to get your co-operation. Either could be enough to begin a process ending in a lengthy prison sentence.

If you've got nothing to hide, you've got nothing to fear. But everyone has a few little secrets. Mass collection ensures that intelligence agencies have the skeletons in everyone's closets stored away in case they ever become useful.

That's without even going into the free speech implications of large-scale surveillance. We talk differently when we're being watched: after all, who talks about their job in exactly the same way when their boss is in the room and listening?

This is just what one small aspect of the NSA's activities revealed over the course of a week. In time, we may know more. But this is the debate the NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden wanted to start. What's being collected, what's allowed under the law, and how much is being done?

Scrutiny so far has been limited: some question whether senators understand the full extent of what's permitted under anti-terror laws they have passed, given the technical knowledge needed to know what is possible. Others worry some congressmen fear to vote in any way which could have them painted as soft on security. Others point to generous campaign contributions from large security contractors – with no comparably generous donors in the privacy lobby.

Snowden's hope is that debate gets wider, more details, more informed, and moves the public.

Perhaps one of the most famous historical quotations on surveillance is attributed to the brutal French 17th-century clergyman and politician Cardinal Richelieu.

"If one would give me six lines written by the hand of the most honest man," he wrote. "I would find something in them to have him hanged."

The NSA, we now know thanks to Snowden's leak, collects more than 200bn pieces of intelligence from computer and phone networks every month. How many could Richelieu hang with that?

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion