The mountains of Norway were once traversed by a variety of hunters and foragers, approximately 6,000 years ago various people traveled through the mountain passes, leaving artifacts of their exploration behind. These artifacts became frozen in glaciers over the years, and now that the glaciers are melting the artifacts left behind over the centuries are being revealed, and endangered.

Though the ice found in the mountains of Norway has kept the artifacts preserved and untouched for thousands of years, the melting ice threatens to expose these fragile artifacts to the elements, degrading them. The melting of the glaciers is driven primarily by climate change, caused by the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. In an effort to save some artifacts from the melting glaciers, an international research team of researchers from the universities of Bergen, Cambridge, Oslo, Oxford, and Trondheim as well as from the Oppland County Council have worked since 2006 to find artifacts amongst the mountains passes.

Over 2,000 Artifacts and 6,000 Years of History

The melting glaciers were located in Oppland County, in the Jotunheimen and Oppland mountain ranges. Exploration of archaeological sites in the area has yielded more than 2,000 artifacts. Some of the artifacts are thought to be over 6,000 years old. The analysis of the finds discovered by the archaeological team was recently published in Royal Society Open Source and covers over a decade of glacier surveying. From 2006 to 2015 the researchers worked to salvage artifacts from the melting glaciers.

At archaeological sites objects made out of organic materials, like textiles, animal hides, or wood, are very rare. This is because they decay over time as microorganisms decompose them. Only a processes which shields organic artifacts from microorganisms, such as being frozen in a glacier, would preserve them.

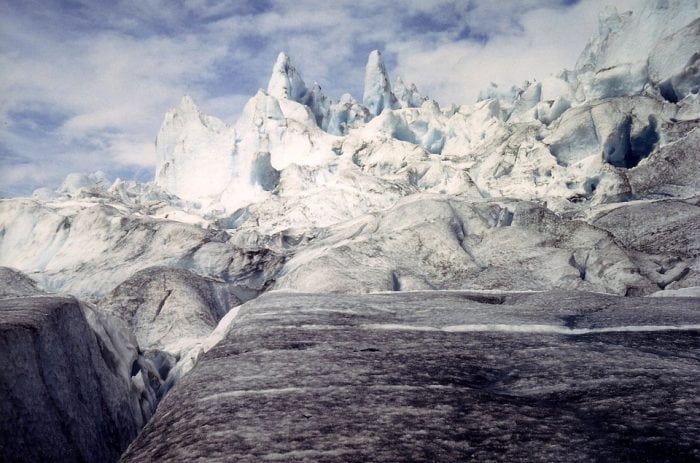

Photo: JohannBargeld via Pixabay, CC0

James Barrett, an archaeologist from the University of Cambridge, stressed how important the work done by the research team was.

Says Barrett:

If something fragile like textile melts out, dries and is windblown it might be lost to science very quickly. Or an arrow might be exposed and then covered again by the next snow, within a few weeks, and remain well-preserved. The unpredictability means the fieldwork, led by Lars Pilø of Oppland County Council, Norway, needs to be well-timed and systematic.

This means that among the various effects of climate change, it threatens to destroy archeologically relevant objects once protected by ice fields.

Hunting and Trading

A Viking era iron seax. Photo: BabelStone via Wikimedia Commons, CC 1.0

The research team found a wide variety of artifacts including clothing from the Bronze Age and Iron Age, parts of sleds and skis dating back to the 8th century, horse skulls, broken bows and arrow shafts, and an inscribed walking stick from the 11th century. Carbon dating of the artifacts reveals that some of the recovered items date back to the start of the Viking Age, around 700 to 900 CE.

Many of the artifacts that were found were tools used to hunt reindeer. Scaring sticks, poles adorned with flags that hunters would form a perimeter to herd the reindeer towards waiting hunters, as well as arrows, were often lost in the snow and left behind. The hunting styles probably changed between the eight to tenth centuries, more advanced tools and weapons came in to use in the later years of this era.

Other artifacts were likely left behind by traders passing through the mountains, as all kinds of tools and clothes were found by the archeologists. Clothes found by the researchers include a tunic from the Iron Age and a shoe from the Bronze Age. The era of the Vikings saw the expansion of trade routes moving through Scandinavia into Europe and the Middle East. Though the famous Viking ships are usually thought of when picturing the expansion of Scandinavia, there were plenty of new trade routes being carved overland, often through mountain passes like those in Jotunheimen and Oppland.

As Scandinavian towns grew so would their exports. Not only would they export food, but hides and furs would be popular exports as well, due to the fact that they are so integral to surviving the cold of Scandinavia. Antlers from reindeer were used to make items like combs and other tools or weapons. Though reindeer hunters would have seen business boom during this era, it is likely that the intensive hunting of reindeer was unsustainable, eradicating the reindeer over the years.

A Changing Climate

Analysis of data collected by radiocarbon dating reveals patterns of boom and bust, periods of high activity in the mountain passes followed by little to no activity. These periods of activity and inactivity correlated with changes in the environment, such as periods of cooling and warming. The researchers think that many of the artifacts recovered from the mountains were left behind during the Medieval Warm Period when the climate warmed and allowed easier access to the mountains of Scandinavia. By contrast, the coldest periods would see the expansion of glaciers and make traversing the mountains difficult if not impossible.

Nonetheless, though fewer people may have risked ascending the mountains during periods of extreme cold, some still did. According to Barrett, hunters kept risking hunting expeditions into the mountains, even during a cold era like the Late Antique Little Ice Age, a brief yet intense period of cold from around 535 CE to 600 CE. The researchers speculate that the cold temperatures caused widespread crop failures, forcing members of Scandinavian villages to turn to mountain hunting to make up for the lack of crops. In other words, despite the adverse climate and weather in the mountain passes, activity continued there out of necessity.

Lars Pilø, from Oppland County Council’s Glacier Archeology Program, says that glacier archeology is a fairly new field. The research team doesn’t do much digging, unlike many other archeologists. Instead, they walk the edges of melting glaciers and mark possible finds with bamboo poles. Though Pilø says the work is exciting and rewarding he also acknowledges that there’s something bittersweet about the work, seeing the glaciers recede before his eyes yet finding valuable artifacts in them. Pilø says that they are “unlikely beneficiaries of global warming”, and calls it a dark kind of archaeology, racing to save artifacts from the changing climate that threatens them.

You can learn more about the artifacts found by the researchers here.