Magazines

Around this time, the first print magazines covering the Amiga platform were starting to appear. The first such magazine was called Amiga World, started by publisher IDG. The premiere issue of the bimonthly magazine reached store shelves in late 1985, and featured the new Amiga 1000 on the cover.

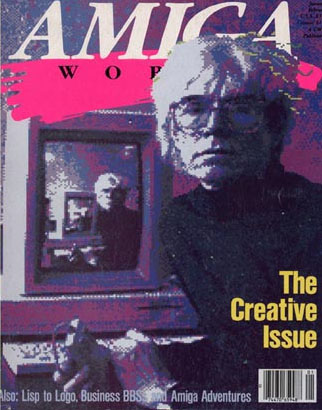

For the second issue, Amiga World tracked down Andy Warhol, who had been one of the stars of the Amiga unveiling. Warhol was an enigmatic personality who ran a magazine called Interview, yet refused to give interviews himself. After brusquely turning down the Amiga World reporter's request for an interview, Warhol retreated to his office upstairs. The undaunted reporter followed Warhol into his office, and while the iconic artist began painting pictures on his Amiga 1000, the journalist started asking him questions anyway.

Andy Warhol on the cover of Amiga World

Image courtesy Amiga History Guide

"Do you like the Amiga? What do you like about it?" the reporter asked.

"I love it. I like it because it looks like my work."

"Do you think it will push the artists?

"That's the best part about it. I guess you can... An artist can really do the whole thing. Actually, he can make a film with everything on it, music and sound and art... everything."

"Why haven't you used computers before?"

"Oh, I don't know, MIT called me for about ten years or so, but I just never went up... maybe it was Yale."

"You just never thought it was interesting enough?"

"Oh no, I did, uh, it's just that, well, this one was so much more advanced than the others."

Warhol was a genius at self-promotion, but his "interview" showed genuine enthusiasm for the Amiga computer. He expressed frustration at not having a color printer yet and talked about how cool it would be to have a graphics tablet and stylus to replace the mouse. These products were all in development, but Warhol wanted them now.

Celebrity endorsements were hardly new in the computer field, but here was something different: a celebrity artist who was a genuine user and enthusiast for the platform. Here was a market—albeit a small one—that could potentially be nurtured.

Repositioning the Amiga

Commodore marketing had positioned the Amiga 1000 as a business machine to compete directly with the IBM PC and its countless clones. This was probably not the best idea.

The average businessman is—let's face it—slow, stodgy, and a bit boring. They are often the last to adopt any new technology unless it can make a clear case for increasing the bottom line. A computer that could print dynamic 3D charts and graphs in color was not going to be useful to a businessman unless there was a whole supporting infrastructure around it: color printers, color overhead display panels, business presentation software, and so forth. This was not the case in 1986.

Thomas Rattigan didn't believe that the business market was the best place to try and sell the Amiga. "I think the price confused a lot of people," he said in a 1987 interview. "People seem to think that home systems are under $1,000 and business systems are over $1,000. I don't think the higher-end Amiga is going to go into accounting departments, but I do think it is going to go into areas where there is a degree of creativity, if you will." In this prediction Rattigan was bang-on.

Rattigan believed that the best strategy was to split the Amiga 1000 into two products: a low-end model to take on the huge home market that had been dominated by the Commodore 64, and a high-end computer that would appeal to graphic artists—like Andy Warhol—who were interested in expanding their system.

reader comments

4