Pain-inducing restraint techniques should only be used on children in custody as an “absolute exception” to save life or prevent serious harm, a long-awaited review has concluded, though it has stopped short of calling for an outright ban.

The review, led by the former chair of the Youth Justice Board Charlie Taylor, examined the inclusion of painful techniques in the minimising and managing painful restraint (MMPR) syllabus, the key training programme for officers in youth custody in England and Wales.

Among 15 recommendations, the report stated the training programme “should be amended to remove the use of pain-inducing techniques from its syllabus” and that “pain is not permitted to be used to end long restraints”.

The report, commissioned by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), does recommend that pain-inducing techniques can be used in exceptional circumstances to prevent serious physical harm to either children or adults.

Taylor criticised the inclusion of such techniques in the MMPR programme, stating: “I believe that this places the use of pain-inducing techniques on a spectrum that makes it an acceptable and normal response rather than what [it] should be, the absolute exception.”

He said this had “contributed to the overuse of these techniques that I so frequently witnessed during this review”.

Taylor also recommended that restraint not be permitted for “good order and discipline” during children’s journeys to and from custodial institutions, though he did say there may be exceptional circumstances “when a member of staff is acting in self-defence and in an emergency”.

A charity, Article 39, started legal action over the authorisation of escort officers from the contractor GEOAmey to use pain-inflicting restraint techniques on children as young as 10 when escorting them to and from secure children’s homes.

Such techniques are banned in the homes themselves but can be used in secure training centres (STCs) and young offender institutions (YOIs).

The charity said the policy was discriminatory, and it also challenged the lack of legal protection for children who could be restrained during their journeys simply for not following orders. Taylor said this should no longer be allowed.

In 2018, the Guardian reported MoJ figures showing that in 2017 there were 97 incidents in which children in custody showed signs of asphyxiation or other danger signs after being restrained, and four serious physical injuries that resulted in hospital admissions.

In 2016, the Guardian revealed that an internal risk assessment of restraint techniques had found that certain procedures approved for use against non-compliant children in custody carried a 40-60% chance of causing injuries affecting the child’s breathing or circulation, the consequences of which could be “catastrophic”.

A year ago, the independent inquiry into child sexual abuse said these techniques were a form of child abuse that must be prohibited by law. The government has yet to respond to that recommendation.

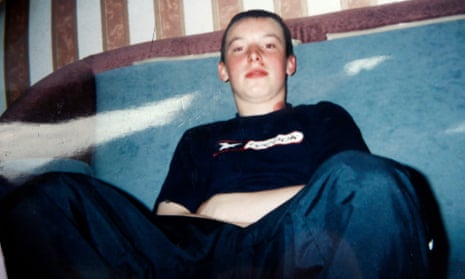

In Hassockfield secure training centre in County Durham in 2004, Adam Rickwood, 14, was restrained for non-compliance using a tactic called nose distraction technique – a karate-like chop to the nose. Adam killed himself shortly afterwards, leaving a letter saying: “What right do they have to hit a child?”

Carolyne Willow, the director of Article 39, said Taylor’s report was “a major milestone in child protection, one we have waited 16 years for since Adam Rickwood hanged himself in a Serco-run child prison. It has taken our legal action to finally bring some promise of justice for Adam and other children who have suffered needlessly over many years.

“We need to see the detail of the legal protections which will be put in place to ensure pain-inducing restraint is genuinely prohibited, and that any emergency, self-defence use of pain complies with common law and the UK’s children’s human rights obligations.”

The MoJ has accepted all of Taylor’s 15 recommendations.