The slow pace of urgent change to prevent deaths in police custody

Three years ago a review of police custody deaths in England and Wales raised hopes of change that might save lives. What happened next?

Last week’s report “Black people, racism and human rights” from the UK Parliament Joint Committee on Human Rights urged that: “recommendations from the Angiolini review of deaths in custody which reference institutional racism, race or discrimination must be acted upon as a matter of urgency.” What progress has been made since Angiolini herself called for urgent change three years ago?

On 30 October 2017, the landmark independent review by Dame Elish Angiolini into deaths and serious incidents in police custody in England and Wales was published. The first and only review of policing practices and the legal processes that follow police related deaths, its recommendations extend to the police service, health service and justice systems. It was seen as a blueprint for change that could save lives. Three years and one progress report later, the government seems to think its job here is done. But our work at INQUEST, a charity that works alongside families bereaved following state related deaths, tells a different story.

The starkest indicator as to the visible progress on Angiolini’s recommendations is the number of deaths of people in police custody. The most recent statistics show that the numbers remain at the same level as 10 years ago. Since the Angiolini review was published, INQUEST’s casework and monitoring indicates there has been 54 further deaths of people in police custody in England and Wales, of which 13 involved restraint. Black people are still more than twice as likely to die in police custody.

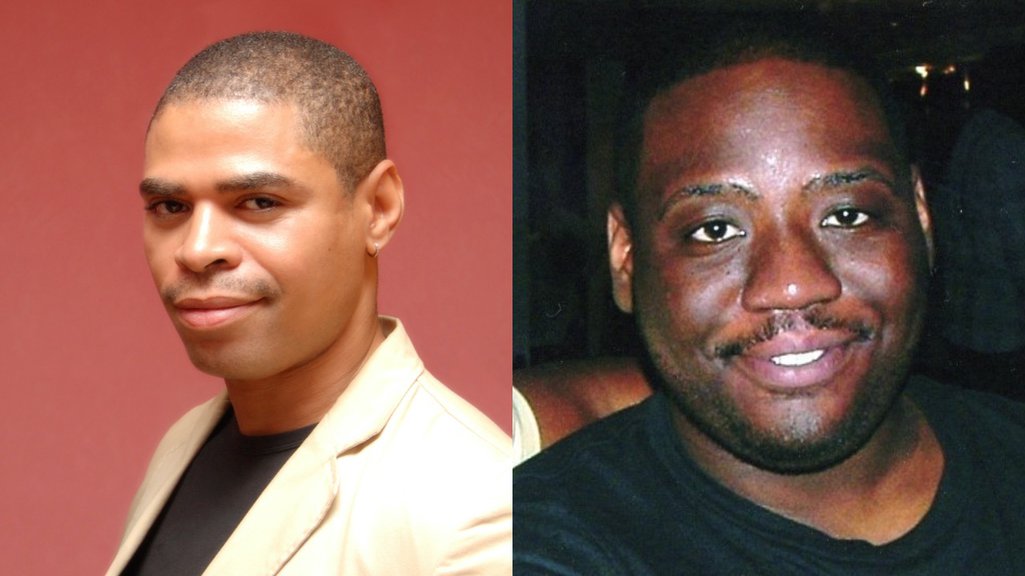

Theresa May, then Home Secretary, commissioned the review after meeting the families of Olaseni Lewis and Sean Rigg, two Black men who died following restraint by police officers whilst suffering mental ill health in 2008 and 2010. Angiolini, the former Solicitor General and Lord Advocate in Scotland, was appointed to take on the review, with INQUEST Director Deborah Coles acting as Special Advisor.

We’ve got a newsletter for everyone

Whatever you’re interested in, there’s a free openDemocracy newsletter for you.

Recommendations in the review sought to address the concerns raised in these cases, such as highlighting that all restraint can cause death and the heightened dangers when someone is in mental health crisis, and the need for police to understand institutional racism and its impact. But only five months after publication, Kevin Clarke, a 35 year old Black man in a mental health crisis died after prolonged and heavy restraint by multiple police officers.

At the inquest into Kevin’s death last month the jury concluded, among a series of damning failings, that the “officers’ decision to use restraint was inappropriate because it was not based on a balanced assessment of the risks to Kevin, compared to the risks to the public and police”. The police told the inquest that they were aware of the risks of restraint, so why was there no attempt at de-escalation and why was restraint used as a first, not a last resort?

“We want mental health services better funded so the first point of response is not just reliant on the police.”

The inquest once again demonstrated the urgent need for structural and cultural change in policing, mental health and healthcare services, one which ends the reliance on police to respond to public health issues, and confronts the reality of institutional racism in our public services. Speaking after the inquest into her son’s death Kevin’s mother Wendy Clarke said: “In his memory we want to see accountability, and real change, not just in training, but the perception and response to Black people by the police and other services. We want mental health services better funded so the first point of response is not just reliant on the police.”

The current processes following deaths continue to fail bereaved families, many of whom remain unable to access anything resembling justice or accountability following a death in police custody. In response to the Angiolini review in October 2017, the then Home Secretary Amber Rudd said the government was “continuing to overhaul the police complaints and disciplinary systems, seeking to ensure that, where misconduct is found, the systems provide a transparent and robust mechanism for holding police officers to account”.

Yet following every contentious death over the past few years, the police have continued a culture of defensiveness and denial, rather than adhering to the explicit duty of candour Angiolini recommended. Time and again misconduct hearings, the disciplinary mechanism for police officers, have been dropped or dismissed following tactics by the police and their representatives to delay or avoid cooperation with the investigation.

Take the gross misconduct disciplinary process earlier this year for five Bedfordshire police officers following the restraint related death of Leon Briggs. The misconduct hearing was stopped before it had even started when Bedfordshire Police force said it would offer no evidence against the officers. Angiolini’s recommendations highlight the importance of accountability at both an individual and corporate level following restraint.

“To be told that the officers will not face any public scrutiny is further denial of justice and accountability.”

Following the decision to withdraw misconduct proceedings, Leon’s mother Margaret Briggs said: “As a family we are devastated and outraged. It is over six years since my son’s death and to be told that the officers will not face any public scrutiny is further denial of justice and accountability for Leon.”

In light of the abandoned misconduct process the focus now falls on the inquest in January 2021 to explore whether the restraint was used in an unnecessary, disproportionate or excessive way.

In the case of Sean Rigg, the misconduct panel dismissed all charges against five officers, despite an inquest jury concluding seven years previously that the level of force was unsuitable, and the restraint was unnecessary and inappropriate. This followed a series of attempts by one police officer, PC Andrew Birks, to appeal his suspension in order to retire and avoid disciplinary proceedings altogether. Such delays only add insult to the already painful and prolonged aftershock of losing a loved one in such traumatic circumstances. Angiolini had proposed a series of recommendations to remedy such delays.

“If the police acted as they were required, why is my brother dead?”

“My question remains, if the police acted as they were required, why is my brother dead? Nothing will tell me that this is justice,” said Marcia Rigg following the decision to dismiss all gross misconduct charges against the officers involved in Sean’s death.

And consider the judicial review brought by the police officer who fatally shot Jermaine Baker. The officer, known as W80, challenged the decision by the Independent Office of Police Conduct (IOPC) to direct the Metropolitan Police to bring misconduct proceedings. The officer’s challenge, which the Court of Appeal rejected, is just one example of police resistance to scrutiny after the use of lethal force. “What is important now is that W80 is held to account for his actions,” said Margaret Smith, Jermaine’s mother after the Court of Appeal handed down its judgement. “The Metropolitan Police Service have fought hard to avoid taking any action against him.”

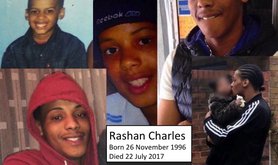

These cases point to police impunity and a process which frustrates the prevention of abuse of power and ill treatment. They are just a few of many examples over the past few years. Others include those relating to the deaths of Olaseni Lewis, Rashan Charles, Adrian McDonald, Thomas Orchard and Duncan Tomlin. The government and state agencies clearly have much work to do before they can claim a “transparent and robust mechanism for holding police officers to account”, but where is the evidence that this work is being done?

Time and again, after deaths and a plethora of recommendations from investigations, inquests, inquiries and reviews, promises are made by the authorities responsible, that learning and action will follow. For the families, each new death exposes the lie in this promise and causes new pain. Indeed, Angiolini said one of the key themes to emerge from the review is the failure to learn lessons.

For this reason, the Angiolini review recommended the government establishes a national “Office for Article 2 Compliance”. Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), as enshrined in the Human Rights Act, places an obligation on the state to protect life. This Office would be accountable to Parliament, and tasked with the collation, dissemination, implementation and monitoring of learning and ensuring the consistency of its application at a national level. INQUEST has also called for the creation of this national oversight mechanism, to monitor deaths in custody and the implementation of official recommendations arising from post death investigations to ensure changes in police and practice are sustained. The government rejected Angiolini’s recommendation, and the evidence of need continues to grow.

Another injustice that unites all families bereaved following a death in police custody is the inequality of arms between themselves and state bodies from the get go. It is imperative that families secure specialist legal advice from the earliest possible stage to provide expertise on matters such as access to the body, post-mortems, communication with investigation teams and securing of evidence. Despite state bodies receiving automatic legal representation which is not subject to a merits or a means test from the taxpayer’s purse, there is no equivalent right for families. INQUEST has long campaigned for legal aid for inquests and Angiolini backed our recommendation. Yet the government rejected the overwhelming evidence in support of non means tested public funding for bereaved families.

As INQUEST Director Deborah Coles has written, families have become powerful advocates for change, turning their grief into resistance and galvanising action against injustice. They have been forced to campaign because of failing systems of investigation and accountability. Their struggles and campaigns have played a critical role in challenging the inequality, racism, discrimination and unacceptable practices of the state. For the bereaved families who invested time, emotion and energy into the Angiolini review, the failure to make progress is a betrayal.

Three years on from the Angiolini review, therefore, INQUEST is calling for the Independent Office for Police Conduct, the Home Office, NHS England and police forces to demonstrate how they have implemented the recommendations of Angiolini. There must be another progress report by the government to provide transparency on what recommendations have been “implemented” and how.

As the Black Lives Matter protests earlier this year saw hundreds of thousands of people across the world come onto the streets and stand in solidarity with George Floyd, attention was rightly drawn to the deaths of people that happen here in the UK. In October every year the United Families and Friends Campaign hold a march in London in memory of everyone who has died in state custody or care. This year on 31 October, due to COVID-19, the event took place online, with bereaved relatives of Christopher Alder, Kingsley Burrell, Darren Neville, Sheku Bayoh, Marc Cole, Cherry Groce, Jack Susianta, Adrian McDonald, Seni Lewis, Sean Rigg, Joseph Scholes, Gaia Pope, Matthew Leahy and others speaking powerfully of their loss and their experience of injustice.

In the United Friends and Family Campaign film (by Migrant Media) Kadija George, a cousin of Sheku Bayoh who died in Kirkaldy, Scotland after what police called a “forceful arrest”, said: “We don’t like welcoming families into our group, because there shouldn’t be a group like this. Nobody should be treated like this.”

Whatever actions have been taken to protect lives, it is clear that it is not enough.

We need to ask, why there is always money for the rollout of ever more powerful Tasers but youth clubs have to shut due to lack of funding? We need to think about how to create a safer and fairer and more equal society. To prevent further deaths and harm, we must look beyond policing and redirect resources into community, health, welfare and specialist services.

Edited by Clare Sambrook for Shine A Light.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.