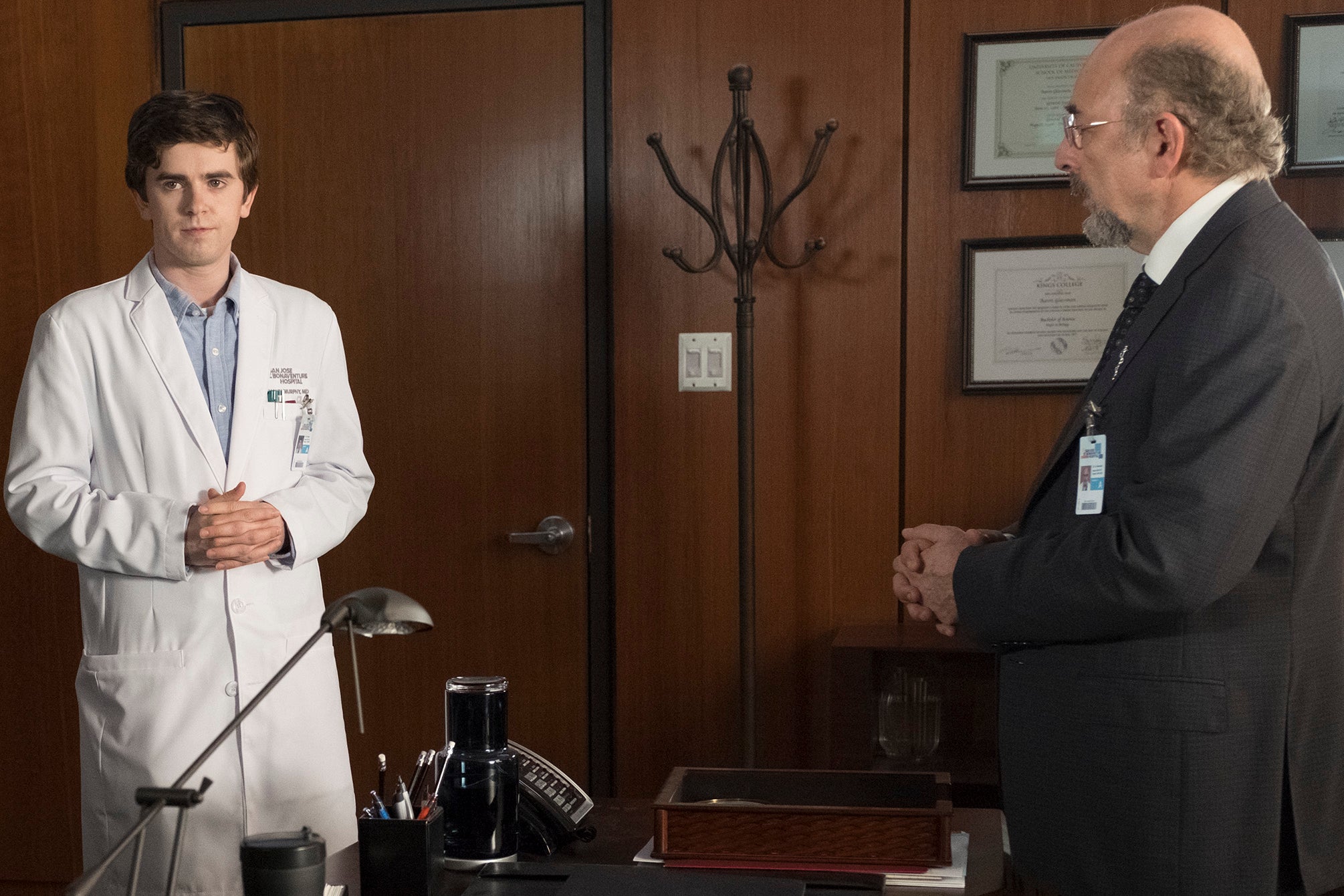

The music is tense as a multicultural, unrealistically attractive team of television doctors works to save their patient. Surgical residents Dr. Jared Kalu (Chukuma Modu) and Dr. Claire Browne (Antonia Thomas) exchange nervous glances, awaiting instructions.* Dr. Browne’s makeup is flawless. They are led by Dr. Neil Melendez (Nicholas Gonzalez), attending surgeon and the rare hospital employee with a visible neck tattoo. A few feet away, Dr. Shaun Murphy (Freddie Highmore), a twitchy, odd genius with a photographic memory, has a beautifully animated epiphany. A bullet weaves its way in and out of a diagram of a rib cage in Dr. Murphy’s mind. He knows where the patient is bleeding. The patient is saved. The music rises and swells in a cheap and obvious bid to evoke an emotional response. I am enthralled.

The Good Doctor is the most-watched drama on television right now. I like competence porn, and so does most of America. This is the first time on TV the skilled, eccentric genius at the center is explicitly autistic, though. This is the first time he’s explicitly like me. And it’s also the first time an autistic person on television has been allowed to be fully human, even if it frequently seems to be by accident. None of the writers of The Good Doctor are autistic. None of the directors. None of the producers. Autistic adults are not in the room at all, although some members of the show’s visual-effects team are in a training program for autistic young adults. Freddie Highmore is not autistic, although he does a decent job portraying one of us on TV. When he plays Dr. Shaun Murphy, he has an “autism accent,” that unusual cadence that many of us speak with. He holds his body the way I hold my body.

In a recent review, the New York Times called Dr. Shaun Murphy an “anti-anti-hero.” As an autistic person, I find the interpretation baffling. Dr. Shaun Murphy is not an abrasive misanthrope like Dr. Gregory House, the subject of David Shore’s previous medical drama. However, he is also not an angelic cinnamon bun in a white coat as many non-autistic viewers and even the writers seem to think he is. He regularly disregards explicit instructions and feigns genuine misunderstanding. The nonautistic people around him, the viewers, and possibly even the writers seem to attribute his disruptive and disrespectful actions to his autism, absolving him of any culpability. Dr. Murphy often contradicts his superior, Dr. Melendez, in front of patients. Dr. Murphy has been explicitly instructed not to multiple times. He continues to do so. It is not because he doesn’t know any better, or because he has had some sort of involuntary vocal tic. Dr. Murphy contradicts Dr. Melendez in front of patients because he does not think that the particular instruction he was given is valid or important. It’s a dynamic that plays out frequently in a variety of situations. Dr. Murphy knows the rules and decides that the rules don’t matter. It’s a House kind of move. People only assume Dr. Murphy’s pure intentions because of his disability.

For example, in the episode “Pipes,” Shaun knocks on his building superintendent’s door late at night to get some nonemergency apartment repairs done. The super is, understandably, upset and extremely explicit about only being contacted during normal business hours. “Unless it’s a fire or a flood, I only work from 9 to 5,” he growls, taking Shaun’s list of requested repairs. Shaun blames Dr. Glassman, the closest thing he has to a parental figure, for the error. After all, Dr. Glassman said he could ask for repairs at “any time.” Shaun took him literally. But Shaun doesn’t take his super literally, though, or seem to listen to him at all. He knocks on the building super’s door late at night, again. There isn’t a fire or a flood in his apartment. Shaun understands perfectly well that he isn’t supposed to go to the building super after hours. He just doesn’t care. He decided his repairs were more important than the superintendent’s stated boundaries.

I’m used to relating to white male eccentrics whose specific skills in some areas make up for their lack of tact. The attraction of competence porn isn’t that Sherlock Holmes and Will Graham have surpassed the need to concern themselves with caring about other people’s feelings. Competence porn appeals to me because these men routinely fail to perform normal human interactions, but people, both within their worlds and the other side of the television screen, love them anyway. I used to fool myself into thinking that if I was brilliant enough, people would love me too. It made my frequent social failures growing up more bearable. I have learned that there is no actual amount of success that will forgive all your sins.

I don’t know if Dr. Murphy recognizes that he is being rude. As an autistic person, it’s often hard to tell how other people feel, which can lead to misunderstandings and hurt feelings. Not knowing, however, is not the same thing as not caring. In clinical terms, there is a difference between affective and cognitive empathy. Autistic people struggle with affective empathy, which means we often have difficulty telling how other people feel based on body language, tone, and other nonverbal tells that may be obvious to others. Cognitive empathy is the capacity to understand another person’s feelings and perspective. Autism does not impair cognitive empathy. Autistic people care deeply about hurting others. I may have a hard time knowing I’ve said something rude to a friend or family member, but if they tell me I hurt them, I feel bad about hurting them. Dr. Murphy has decided that because he doesn’t feel what he’s saying is rude, what he is saying is, objectively, not rude. That’s not autism. That’s being a jerk.

Autistic people rarely get portrayed as real, complete human beings. In Netflix’s Atypical, the autistic main character, Sam, is essentially a diagnostic checklist, not a whole person. He’s hollow inside—there’s nothing in his mind except sex and penguins. The show isn’t really about Sam. The show is about Sam’s autism, and how it affects Sam’s family. He is, in many way, a plot device in what is supposed to be his own story. The Good Doctor does not fall into the trap of being about how autism “affects families.” Instead, it portrays an autistic adult as a whole, complex person. This is partially due to the source material: Shaun Murphy’s Korean counterpart is an orphan, and on the U.S. version, he’s at least estranged from his abusive parents, to the extent it’s not clear if they’re still living or not. The show cannot tell the vomitously overused story of strained marriages and put-upon siblings because there is no marriage and there are no siblings. As a result, the writers are forced to write a story that is actually about Shaun. They and the viewers are forced to empathize with Shaun. It’s the best representation of an autistic person I’ve ever seen on television. I strongly suspect it isn’t on purpose. I don’t care.

Correction, Dec. 29, 2017: This post originally misidentified the character Dr. Jared Kalu as Dr. Jared Balu. It also misspelled Chukuma Modu’s first name.