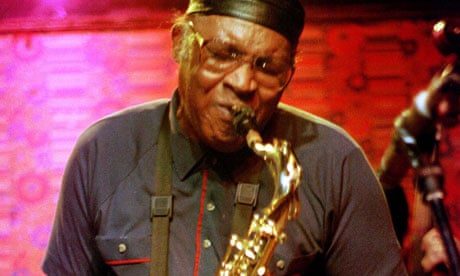

New Orleans and New York are usually the frontrunners for iconic jazz towns, but Chicago comes very close. Louis Armstrong and the pioneering New Orleans jazz wave moved there in the northward migrations of the early 20th century; Benny Goodman, Bix Beiderbecke and the early white stylists developed their own brand of swing there in the late 20s; and in the 1960s the city was home to free-jazz experimenters such as the saxophonist Fred Anderson, who has died aged 81. Anderson had Chicago stamped through him like a stick of rock. He moved there in childhood, raised a family and played in the city all his life – significant reasons why he wasn't more widely known in the US and abroad.

Chicago free-jazzers have often displayed a knack for balancing the uncompromisingly edgy with the quirkily convivial, and Anderson embodied those virtues as a player. His approach was indebted to Charlie Parker whom he heard "singing through the horn" at the South Side's Pershing Lounge in the late 1940s. Anderson was also attracted to the proto-soul-jazz sound of bop tenorist Gene Ammons. But sax players with leanings toward early R&B and raw blues often had a cavalier approach to conventional pitch – the free-jazz pioneer Ornette Coleman, a significant later influence on Anderson, being the prime example.

Anderson could microtonally bend notes with an insouciance that brought him accolades from fans and doubts about his competence from sceptics. He lasted long enough to see a much more open attitude to music's global vocabularies prevail, but it was a tough slog. The comfort zone of his club, the Velvet Lounge, and its hip audiences saw him through long periods of it.

He was born in Monroe, Louisiana. In his 20s, he studied harmony and theory at Roy Knapp's music school in Chicago's South Side. In 1965, Anderson joined one of Chicago's most respected and progressive musicians, the pianist Muhal Richard Abrams, in founding the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). This co-operative, which advocated deep absorption in the jazz tradition and openness to performance art and what would eventually be considered "world music", was an inspiration to many radical Chicago musicians. Anderson played at the AACM's opening concert in 1965, and the following year made his recording debut on Joseph Jarman's album Song For.

Anderson continued to develop his playing, with more explicit strands influenced by Coleman and John Coltrane becoming audible, but he was his own unique teacher, even working out books of personal technical exercises informed entirely by his own enthusiasms.

In his later years, Anderson began to formalise these documents for the use of students, notably with the book Exercises for the Creative Musician – transcriptions of several of his improvised solos notated by a University of Chicago music student and annotated and explained by Anderson. He increasingly saw his role as enabling young jazz improvisers to discover their own sounds and ways of playing through exercises that freed their individuality rather than taught them a formula.

In the 1970s, he ran a non-profit club called the Birdhouse (named in Parker's honour) on the North Side. He formed a regular band including his drummer son Eugene, the percussionist Hamid Drake and a shifting cast of Chicago adventurers. Anderson also recorded in Italy with Drake and the trumpeter Billy Brimfield. Returning home, he worked as a bartender for the ailing proprietor of Tip's Lounge on Indiana Avenue. He bought the establishment on the owner's death (aided by a property sale following his divorce from his wife Bernice) and reopened it as the Velvet Lounge in 1982. Anderson declared that a complimentary observation about the warmth of his sax sound had given him the idea for the name.

The venue became a spiritual home to many musicians who shared the uncommercial player's perennial need for an intimate space run by, and for, the people who cared. Anderson was a tireless battler in the generally unrewarding world of jazz promotion – a source of creative inspiration, advice and practical support. He ran open jam sessions at the venue on alternate Sunday afternoons.

His playing and recording career blossomed, and many sessions captured live at the club (featuring Drake, Ken Vandermark and a visiting bassist, Peter Kowald, among others) found their way on to independent labels. In 2006, a condominium development forced Anderson out, but donors and local musicians raised funds for a new Lounge which opened nearby three months later.

Anderson's crucial role in the evolution of post-60s Chicago jazz, and his unique sound as an improviser, became much more widely appreciated after the millennium. New recordings such as his duet with the drummer Robert Barry were released, and the 1979 album Dark Day (made at Chicago's Museum of Contemporary Art, and in Verona) was reissued after a long absence by the independent label Atavistic.

In 2002, the Chicago Jazz festival staged an orchestral performance of the Dark Day track Saxoon in Anderson's honour. Last year, he was moved by the crowds attending his 80th birthday gig ("I didn't know that many people were checking out my music.") He had been due to play New York's Vision festival on the day of his death. "Those who come through here learn how to listen and how to play with each other, which is very difficult," he once said, explaining his single-minded devotion to the Velvet Lounge. "That's how jazz has developed from the beginning."

A son, Kevin, predeceased him. Anderson is survived by his other sons, Michael and Eugene, and by five grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.