ウミサソリ

| ウミサソリ | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| 地質時代 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 古生代オルドビス紀ダリウィル期 - ペルム紀チャンシンジアン期 (4億6,730万 - 2億5,200万年前)[1][2] | ||||||||||||||||||

| 分類 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| 学名 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Eurypterida Burmeister, 1843 | ||||||||||||||||||

| シノニム | ||||||||||||||||||

| 和名 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ウミサソリ目[5][6] 広翼目 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 英名 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sea scorpion Eurypterid | ||||||||||||||||||

| 亜目 | ||||||||||||||||||

ウミサソリ(海蠍[5]、英: sea scorpion)、別名広翼類(こうよくるい、英: eurypterid[6], 学名: Eurypterida)は、鋏角類に属する化石節足動物の分類群の一つ。分類学上はウミサソリ目(広翼目)とされる。しずく型の体と、腹面の生殖器周辺に融合した外骨格をもつ[7][8]。和名および英名などの通称にサソリ(scorpion)の名が付くが、サソリではない。

知られる最古の化石記録は古生代オルドビス紀ダリウィル期(約4億6,730万年前)まで遡り[1]、シルル紀からデボン紀にかけて栄えた水棲動物で、特にシルル紀には海中の頂点捕食者とされる種類もあった。約2億年間の長い生息時代にあったが、知られる最晩期の化石記録はペルム紀チャンシンジアン期(約2億5,200万 – 2億5,400万年前)までで、古生代を終わらせたペルム紀末の大絶滅(P-T境界)で絶滅した[2]。

約250種が知られ、化石鋏角類の中では最も種に富んだ分類群である[4]。1メートル前後の大型種が多く[9]、最大級のものは2.5メートルにも達すると推測され、これは既知で史上最大級の節足動物となる[10]。ウミサソリ類として一般的周知の種類は、紹介例の多いユーリプテルスとプテリゴトゥスである。

名称[編集]

学名「Eurypterida」は本群の一属であるユーリプテルスの学名「Eurypterus」(古代ギリシア語の「ευρυς」 (eurys, 幅広い[5]) と「πτερον」(pteron, 翼)の合成語[11][12])に、一般的に目階級の分類群の学名に使われる語尾のひとつ「-ida」を添えたもの[13]。シノニム(異名)に「オオサソリ目[14] Gigantostraca」と「Cyrtoctenida」がある[4]。

英語では通称である「sea scorpion」の他に学名「Eurypterida」に因んだ学術的総称「eurypterid」がある[12]。中国語では訳語に「鱟」(カブトガニ)の字を付け足して「廣翅鱟」(簡体字: 广翅鲎)と呼ぶ。ほかに「板足鱟」(簡体字: 板足鲎)や「海蝎」の名もある。和名としてそれぞれ英語の「sea scorpion」と「eurypterid」に対応する「ウミサソリ(漢字転写: 海蠍)」と「広翼類」がある[5][6]。

形態[編集]

-

最大級ウミサソリの6種とヒトのサイズ比較図。左からプテリゴトゥス(Pterygotus grandidentatus)、ペンテコプテルス (Pentecopterus decorahensis),アキュティラムス2種(Acutiramus macrophthalmus と Acutiramus bohemicus) カルシノソマ(Carcinosoma punctatum)、およびイェーケロプテルス(Jaekelopterus rhenaniae)。

体はしずく型に縦長く、前後に甲羅状の前体と、分節した後体という2つの合体節に分かれている[8]。重厚な体型をもつヒベルトプテルス科(Hibbertopteridae)を除いて、通常は上下に平たい。ほとんどの種類は大型の節足動物であり、数十cmから1m前後に及ぶのものが多い[15][16]。2m以上にも達し、既知最大級の節足動物として知られる種もある[10]が、数cmしか及ばない小型種も含まれる[16]。

前体[編集]

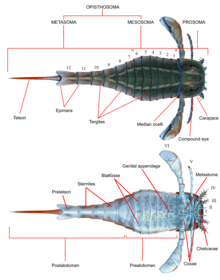

前体(prosoma, 頭胸部 cephalothorax ともいうが、頭部そのものに相当[17])は眼や口などが由来する先節と、6対の前体付属肢(後述)が由来する直後6節の体節(第1-6体節)の融合でできた合体節と考えられる[8]。1枚の背甲(carapace, prosomal dorsal shield[8])に覆われ、その背面左右に複眼である側眼(lateral eye)[18]と、中央に単眼である中眼(median eye)をそれぞれ1対をもつ。背甲の縁辺部は出張っているが、カブトガニ類ほど極端でなく、その下にある全ての付属肢全体を覆う程度にはならない。背甲の腹面は縁に沿って折り返した外骨格構造(doublure[19] または ventral plate[20])があり、分類群によって1枚から5枚ほど細分される[19][21][7][22]。カブトガニ類に似て、この外骨格と背甲の境目、すなわち背甲の縁辺部は脱皮の割れ目でもある[20]。付属肢に囲まれた腹面中央には「endostoma」という目立たない二葉状の外骨格があり[21]、一般にはカブトガニ類のと同じ前体の腹板(sternite, sternum)由来とされるが[8]、ウミサソリの場合は文献により第5脚基節から遊離した顎基[23]・第7体節の付属肢との異説もある[24]。この外骨格の直前には、口とそれを覆い被さった目立たない上唇(labrum)と口上板(epistome)の複合体がある[23][25]。

鋏角と脚[編集]

-

発達した鋏角をもつプテリゴトゥス

他の真鋏角類と同様、前体の腹面は1対の鋏角(chelicera)と5対の歩脚型付属肢(脚)という計6対の付属肢(関節肢)をもつ[8]。鋏角は鋏型で3節の肢節(柄部1節と鋏2節)からなり[26][8]、基部は口上板と上唇の複合体に関節する[23][25]。通常では完全に前体に隠れるほど短く目立たないが、ミラーウミサソリ科[6](Hughmilleriidae)のは背甲の前縁をやや超えるほど大きく[21][27]、ダイオウウミサソリ科(Pterygotidae)のは更に極端に発達し、腕のように長く伸びていた[21][22][26][19][27]。

鋏角の直後に続く5対の脚は後方ほど多くの肢節に分かれ(原則として第1脚7節、第2-3脚8節、第4-第5脚9節)[23][1]、分類群や番目によって単調な歩脚状からやや特殊な形に特化したものがある[19][1][28]。それぞれの脚の基部(基節 coxa)は、口を囲んだ咀嚼器である鋸歯状の顎基(gnathobase)をもつ[29]。最初1対の脚は触肢(pedipalp)で、通常は形態的に脚から分化していないが、分類群や雌雄[23]によってある程度の特化が見られる場合もある[19]。最終1対の脚は、ウミサソリ亜目(Eurypterina)では第7肢節先端内側に「podomere 7A」という構造体がある[30]。その中でMoselopteridae 科以外の種類は顕著に特化した遊泳脚(swimming leg)で、第7肢節・第8肢節・podomere 7A が偏平で、櫂状のパドル(paddle, swimming paddle)を構成する[19][30]。アシナガウミサソリ亜目(Stylonurina)の場合、この脚は podomere 7A をもたず、歩脚型のままである[19][30][31]。

後体[編集]

-

様々なウミサソリの下層板

後体(opisthosoma, 腹部 abdomen ともいうが、胴部に相当[17])は長く伸び、背面の背板(tergite)は12節に見えるが、実際には13節(第7-19体節)の合体節で、そのうちの後体第1節(第7体節)の背板が観察できないほど退化していたと考えられる[8]。通常は4枚目の背板で最も幅広い[7]が、Mycteropidae 科のように1-2枚目の背板で最も幅広い分類群もある[31]。背板の両後端は分類群や番目によって棘(epimera)があったりなかったりする[19][7]。腹面は体節ごとに腹板(sternite)が並んでいるが、最終6節のみ顕著に見られ、前半の腹板は退化的か完全に蓋板(後述)に覆われている[7]。最終5節は背板と腹板が融合してリング状の体環になる[8]。後体の末端には1本の尾節(telson)があり、通常は剣状に尖るが、へら状のものもある(スリモニア科、ダイオウウミサソリ科など)[19][32][27][8]。尾節直前の最終体節は「pretelson」ともいい、形がやや特化した場合がある[27]。

一部の分類群では、後体はサソリのように明確に前後で幅広い前半部と細長い後半部に分化し、それぞれ中体(mesosoma)と終体(metasoma)、もしくは前腹部(preabdomen)と後腹部(postabdomen)と呼ばれている[19][8]。一方で、このような分化の有無にかかわらず、付属肢の有無に基づいてウミサソリ全般の後体前7節(後体第1節と第1-6背板に相当、付属肢のある部分)を中体、後6節(第7-12背板に相当、付属肢のない部分)を終体と扱う文献記載もある[7][17][8]。

退化的な後体第1節をも含めて、後体の前7節(第7-13体節)の腹面には後述の板状の付属肢が配置される[8]。

下層板[編集]

カスマタスピス類などに似て、後体の前端には下層板(metastoma)[6]という、前体最終の脚の間に伸びた1枚の小さな板状構造をもつ。これは一般にはカブトガニ類の唇様肢に相同で、退化的な後体第1節に由来する、左右融合した1対の付属肢だと考えられる[7][17][33][8]。その形は種類によって単調な楕円形から丸みを帯びた四辺形や三角形まで多岐にわたる[19]。アシナガウミサソリ亜目の場合、下層板の正中線には1本の縦溝がある[31]。

蓋板と生殖器[編集]

(彩色:生殖口蓋、灰色:Blatfüsse)

下層板以降の後体第2-7節は、6対の蓋板(がいばん、operculum)という平板状の付属肢があり、体節の腹面(腹板)を覆い被さるように後ろに向けて畳んでいる[8]。体節に密着し、カブトガニ類の蓋板ほどの運動能力はなかったと考えられる[34]。最初2対の蓋板は前後融合した生殖口蓋(genital operculum)、残り4対の独立した蓋板は「Blatfüsse」(単形: Blatfuss)と呼ばれている[8]。Blatfüsse は通常では全てが左右融合しているが、中央の溝(central sulture)で左右に分かれた場合もある[35]。

最初1対(後体第2節)の蓋板のみでできた他の真鋏角類の生殖口蓋とは異なり、ウミサソリの生殖口蓋は、前後融合した最初2対(後体第2-3節)の蓋板に構成されており、この特徴はウミサソリを明確に他の類似群(特にカスマタスピス類)から区別させた最も重要な共有派生形質である[7][36][17][8]。そのうち後体第2節の蓋板に当たる板は「median opercular plate」、後体第3節の蓋板に当たる板は「posterior opercular plate」と呼ばれている[7]。アシナガウミサソリ亜目と基盤的なウミサソリ亜目の種類では、生殖口蓋は更に「anterior opercular plate」という短縮した板が前端にあり、これは後体第1節の腹板由来の部分と考えられる[7]。派生的なウミサソリ亜目(Diploperculata下目)の種類では anterior opercular plate をもたず[36]、残りの板は更に融合が進み、境目に当たる溝(transverse suture)が見えないほど一体化していた[7]。また、posterior opercular plate の中央には「spatulae」という生殖肢の左右に並んだ1対の突起物をもつ場合がある[19][37]。

生殖口蓋の中央には1本の生殖肢(genital appendage)をもつ[8]。これは後体第2節の蓋板に由来し[7]、その1対の内肢が左右融合してできた生殖器と考えられる[37]。基部は「deltoid plate」という1対の三角形/五角形の外骨格に連結し[19][7]、これは生殖肢の運動に関与する構造と考えられる[38]。生殖肢は同種において長いタイプ(type A)と短いタイプ(type B)というはっきりとした二形が見られ、これは雌雄を表す特徴と考えられる[39][38]が、それぞれに対応する性別(どっちが雄でどっちが雌か)は諸説に分かれている[35]。特に type A の場合、生殖肢の根元に「horn organ」という1対の長い嚢状の内部構造があり、これは文献記載によって(雌の)受精嚢[40]もしくは(雄の)精莢を生成する器官[35]と考えられる。この生殖肢、特に type A は通常では3節に分かれるが、ダイオウウミサソリ科の場合は雌雄とも生殖肢が分節しない[27][7]。

呼吸器[編集]

ウミサソリの呼吸器を保存した化石は非常に稀で、その構造は20世紀後期以前では長らく不明確とされ、その復元も新たな発見によって更新され続けていた[41][42][43][44]。2020年時点では、書鰓(しょさい、book gill)と「Kiemenplatten」という2種類の呼吸器をもつことが分かり、いずれも5対で後体第3-7節に付属したとされる[44]。

書鰓は後方5対の蓋板[44]、いわゆる生殖口蓋の posterior opercular plate と4対の Blatfüsse の裏側に配置される[42][8]。書鰓の位置と大まかな形態はカブトガニ類に似ているが、顕微構造はむしろクモガタ類の書肺(しょはい、book lung)に近い[44]。Kiemenplatten(gill tract とも[41])は多孔質のクチクラと数多くの短い突起物に構成される一面の構造体で、書鰓を有する蓋板の上側、いわゆる該当体節の腹板で対になって配置される[41][42][8]。この2種類の呼吸器はそれぞれ別起源で、書鰓は他の真鋏角類の書鰓と書肺に相同の祖先形質、Kiemenplatten はウミサソリに特有の二次的な呼吸器と考えられる[42][8][44]。書鰓を有する蓋板と Kiemenplatten を有する腹板は、あわせてウミサソリの鰓室(gill chamber, branchial chamber)の内壁を構成する[42][8]。

ウミサソリの呼吸器が発見される以前から、既にカブトガニ類のように5対の書鰓があると推測された[21]。最初に発見されたのは Kiemenplatten で、Laure 1893 に蓋板由来と解釈された[45]が、Moore 1941 以降では腹板由来と見直された[46]。Waterston 1975 ではウミサソリは Kiemenplatten という1種類の呼吸器のみをもつと考えられた[41]が、Kiemenplatten と(未発見の)書鰓という2種類の呼吸器を兼ね備える説もあり[47]、この解釈は Manning & Dunlop 1995 で断片化石から得られる情報にも示唆される[42]。複数対の書鰓が体と共に保存したウミサソリの化石は Braddy 1999 で最初に発見されたが、その書鰓は不完全で、4対で外側の部分のみ保存されるため、ウミサソリの書鰓は数・配置ともサソリの書肺に共通すると解釈された(後体第3節に書鰓はなく、第4-7節にある4対の書鰓は縦方向に並んでいる)[43]。こうしてウミサソリの呼吸器は5対の Kiemenplatten と4対の書鰓を兼ね備えると考えられた[8]が、Lamsdell et al. 2020 ではカブトガニ類のように水平に並んだ完全の書鰓と、生殖口蓋の(後体第3節由来の)posterior opercular plate に付属する書鰓が発見されており、ウミサソリの書鰓は数・配置ともカブトガニ類に共通だと判明した(5対の書鰓は後体第3-7節で水平方向に配置される)[44]。

生態[編集]

ウミサソリは全般的に捕食者とされ、分類群によっては様々な捕食方法への特化様式が見られる[28]。遊泳性で獰猛な捕食性に適したようなものがあれば、底生性で堆積物から小さな獲物を篩い分けるのに適したようなものもある[49][50][18][28]。その捕食行動によって残されたと思われる生痕化石も知られている[51]。ウミサソリ亜目とアシナガウミサソリ亜目の種類は、それぞれ前述の2つのニッチ(生態的地位)に向けて特化した傾向がある[16]。

ウミサソリ亜目の遊泳脚をもつ種類は、その遊泳脚で水中を泳いでいたことは広く認められるが、遊泳の仕組みは諸説に分かれ[34]、文献によっては遊泳脚の前後動作とパドルの角度変換で推進力を生じ[23][52]、もしくは遊泳脚を翼のように動かして揚力で前進していたと考えられる[53][34]。中型以下で大きな遊泳脚をもつもの(例えばウミサソリ科)は推進力、大型で小さな遊泳脚をもつもの(例えばダイオウウミサソリ科)は揚力という、種類によって遊泳方法が異なっていたとの説もある[34]。

名前に反して、ウミサソリ類は必ずしも海に限らず、淡水域に棲息する種類も数多く知られ、初期の海中からだんだんと浅海や淡水へと進出したことも化石記録によって示唆される[9][16][18]。少なくとも一部の種類は陸上にある程度に進出した可能性があり、それを示唆する足跡の生痕化石[48]も発見されている。また、その呼吸器から空気呼吸に適したような構造も発見される(Kiemenplatten の構造は陸棲甲殻類の偽気管に似る[42]、書鰓のラメラの隙間にはクモガタ類の書肺に共通する小柱がある[44])。

複雑な生殖器をもつことにより、ウミサソリはカブトガニ類のような体外受精をせず、むしろクモガタ類のように体内受精をし、配偶行動として雌雄が特化した生殖肢を用いて精莢の受け渡し(交接)を行っていたと考えられる[40][35]。

分類[編集]

左下:カスマタスピス、右下:ディプロアスピス

| 節足動物 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

従来、節足動物の中でウミサソリ類は共通点(複眼の構造[18]・発達した背甲・脚の顎基など)の多いカブトガニ類(剣尾類 Xiphosura)と共に、節口類(腿口類 Merostomata)としてまとめられた[54][55][7][18]。節口類は19世紀では甲殻類扱いされてきた[54]が、20世紀以降ではむしろクモガタ類(蛛形類 Arachnida)などに共通な基本体制が判明し、共に鋏角類(Chelicerata)としてまとめられるようになった[56]。

20世紀後期以降では、精莢の受け渡しに適した硬質な生殖器などの形質に基づいて[35][17]、ウミサソリ類は同じ節口類のカブトガニ類より、むしろクモガタ類に近縁である(Sclerophorata[35] もしくは Metastomata[57] を構成する)説が主流となっている[57][58][59][35][17][8][18]。これによると、ウミサソリ類を含んだ節口類はクモガタ類を除いた側系統群であり[7][18](もしくはウミサソリ類を節口類から除外する[17])、カブトガニ類とウミサソリの多くの共通点は、あくまでも真鋏角類の祖先形質を表しているに過ぎない[18]。もしクモガタ類は節口類に対して多系統群であれば、ウミサソリ類は蛛肺類(サソリ・クモ・ウデムシ・サソリモドキなどを含んだ系統群)のクモガタ類に近縁と考えられる[44]。

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 真鋏角類の中で、クモガタ類が多系統群であった場合のウミサソリ類の系統的位置[44]。 |

ネジムシ(カスマタスピス Chasmataspis)[6] やディプロアスピス[60]をはじめとし、全体の姿と後体付属肢の構成(同じく下層板と生殖肢をもつ)が本群によく似たカスマタスピス類[60]との類縁関係も議論の的となっている。この分類群に対しては、カブトガニ類とウミサソリ類に対して多系統群・ウミサソリ類に至る側系統群・カブトガニ類に含まれる・ウミサソリ類に含まれるなどの説はあった[61]が、2010年代以降では独立した単系統群でありつつ、ウミサソリ類・クモガタ類と単系統群(Dekatriata)になる説の方が主流である[17][33][62][63]。

また、後体の構成と呼吸器の配置などに基づいて、ウミサソリ類をサソリに最も近縁とする異説もあった[43][64][65]が、この見解は21世紀以降の研究に支持されず[66]、両者の共通点は Dekatriata 類の祖先形質[17]、もしくは収斂進化の結果[67]と見なされる。

下位分類[編集]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lamsdell et al. (2013) に基づいたウミサソリ類の各上科の系統関係[36] |

2020年現在、約250種のウミサソリ類が記載され、2亜目12上科21科70前後の属に分類される[4]。

ウミサソリ類は大きくアシナガウミサソリ亜目(Stylonurina)とウミサソリ亜目(Eurypterina)の2つに分かれ、大部分の種類は後者に分類される[9][16][4]。アシナガウミサソリ亜目は形態が祖先的であるため、更に全面的な系統解析がなされるとウミサソリ亜目に対して側系統群になる可能性もあるが、両亜目とも単系統群で姉妹群であることがほとんどの系統解析に支持される[16][31][36][37][1][68]。

特殊な形態をもつヒベルトプテルス科(Hibbertopteridae)をウミサソリ類から区別させる意見もあるが、この科はアシナガウミサソリ亜目における派生群であることが多くの系統解析に支持される[31][68][4]。

ウミサソリ亜目の中で、まずモセロプテルス上科(Moselopteroidea, 第5脚は歩脚型)とオニコプテレラ上科(Onychopterelloidea, 第5脚は歩脚型と遊泳脚型の中間形態)は本亜目の遊泳脚の進化を表しているように順に分岐し[30]、続いてウミサソリ上科(Eurypteroidea)は残りの上科に至る側系統群と考えられる[36]。残りの上科(ハリウデウミサソリ上科 Mixopteroidea, Waeringopteroidea 上科, トゲウミサソリ上科 Adelophthalmoidea, プテリゴトゥス上科 Pterygotioidea)はいわゆる派生的なウミサソリ類[7]で、生殖口蓋は前端の板をもたず、残り2枚の板は境目が見当たらないほど融合した[7][36]。この特徴に因んで、これらの上科は Diploperculata(「二つ」を意味する古代ギリシア語「διπλόω」と蓋板を意味する「operculum」の合成語)下目としてまとめられる[36]。

以下の分類体系とそれぞれの地質時代は、脚注と特記しない限り World Spider Catalog に掲載される化石鋏角類一覧表「A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives」(最終更新日:2020年1月15日)に基づく[4]。属より上位の分類群は太字で示す。

- ウミサソリ目 Eurypterida †(=オオサソリ目 Gigantostraca, Cyrtoctenida)(オルドビス紀 - ペルム紀)

- アシナガウミサソリ亜目[6] Stylonurina Diener, 1924(=Woodwardopterina, Hibbertopterina)(オルドビス紀 - ペルム紀)

- (上科・科未定)

- (属)'Stylonuroides'(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- (上科)Rhenopteroidea(=Brachyopterelloidea)(オルドビス紀 - デボン紀)

- レノプテルス科[60] Rhenopteridae (=Brachyopterellidae)

- ブラキオプテレラ[60]属 Brachyopterella(シルル紀)

- ブラキオプテルス[60]属 Brachyopterus(オルドビス紀)

- キアエロプテルス[60]属 Kiaeropterus(シルル紀)

- (属)Leiopterella(デボン紀)

- レノプテルス[60]属 Rhenopterus(デボン紀)

- レノプテルス科[60] Rhenopteridae (=Brachyopterellidae)

- アシナガウミサソリ上科[6] Stylonuroidea(=Drepanopteroidea)(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- パラスティロヌルス科 Parastylonuridae(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- パラスティロヌルス[60]属 Parastylonurus(シルル紀)

- (属)Stylonurella(シルル紀? - デボン紀)

- アシナガウミサソリ科[6] Stylonuridae(=Laurieipteridae, Pageidae)(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- (属)Ctenopterus(シルル紀)

- (属)Laurieipterus(シルル紀)

- パゲア[60]属 Pagea(デボン紀)

- スティロヌルス属 Stylonurus(デボン紀)

- (属)Soligorskopterus[69](デボン紀)

- パラスティロヌルス科 Parastylonuridae(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- ココモプテルス上科 Kokomopteroidea(シルル紀)

- ミクテロプス上科 Mycteropoidea (=ヒベルトプテルス上科 Hibbertopteroidea)(シルル紀 - ペルム紀)

- カマアシウミサソリ科[6] Drepanopteridae(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- ヒベルトプテルス科 Hibbertopteridae(=Cyrtoctenidae)(デボン紀 - ペルム紀)

- カンピロセファルス[60]属 Campylocephalus(石炭紀 - ペルム紀)

- (属)Cyrtoctenus(デボン紀 - 石炭紀)

- (属)Dunsopterus(デボン紀 - 石炭紀)

- ハスティミア[60]属 Hastimima(ペルム紀)

- ヒベルトプテルス属 Hibbertopterus(石炭紀 - ペルム紀)

- (属)Vernonopterus(石炭紀 - ペルム紀)

- ミクテロプス科 Mycteropidae (=ウッドワードウミサソリ科[6] Woodwardopteridae)(石炭紀 - ペルム紀)

- メガラクネ[60](メガラシネ)属 Megarachne(石炭紀 - ペルム紀)

- ミクテロプス[60]属 Mycterops(石炭紀)

- (属)Woodwardopterus(石炭紀 - ?ペルム紀[2])

- (上科・科未定)

- ウミサソリ亜目[6] Eurypterina Burmeister, 1843(オルドビス紀 - ペルム紀)

- オニコプテレラ上科 Onychopterelloidea(オルドビス紀 - シルル紀)

- オニコプテレラ科 Onychopterellidae (=Alkenopteridae)

- (属)Alkenopterus(デボン紀)

- オニコプテレラ[60]属 Onychopterella(オルドビス紀)

- (属)Tylopterella(シルル紀)

- オニコプテレラ科 Onychopterellidae (=Alkenopteridae)

- モセロプテルス上科 Moselopteroidea(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- モセロプテルス科 Moselopteridae

- モセロプテルス[60]属 Moselopterus(デボン紀)

- ストエルメロプテルス[70]属 Stoermeropterus(シルル紀)

- (属)Vinetopterus(デボン紀)

- モセロプテルス科 Moselopteridae

- ヒレオウミサソリ上科[6] Megalograptoidea(本上科の種類は Lamsdell et al. (2013) 以降の系統解析にDiploperculata 下目に含まれる[36][37][1][68])(オルドビス紀)

- ‘ウミサソリ上科[6] Eurypteroidea’(単系統性が Lamsdell et al. (2013) に疑問視される[36][4])(オルドビス紀 - デボン紀)

- (科所属不確実)

- (属)Paraeurypterus(オルドビス紀)

- (属)Pentlandopterus(オルドビス紀)

- カイナガウミサソリ科[6] Dolichopteridae(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- (属)Clarkeipterus(シルル紀)

- ドリコプテルス[60]属 Dolichopterus(シルル紀)

- (属)Ruedemannipterus(シルル紀)

- ウミサソリ科[6] Eurypteridae(シルル紀)

- (科)Erieopteridae(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- (科)Strobilopteridae(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- (属)Buffalopterus(シルル紀)

- ストロビロプテルス[60]属 Strobilopterus(=Syntomopterus, Syntomopterella)(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- (科所属不確実)

- (下目[36])Diploperculata(オルドビス紀 - デボン紀)

- カルシノソーマ上科 Carcinosomatoidea(=ハリウデウミサソリ上科[6] Mixopteroidea)(オルドビス紀 - デボン紀)

- ハラビロウミサソリ科[6] Carcinosomatidae(オルドビス紀 - デボン紀)

- カルシノソーマ[60]属 Carcinosoma(=Eurysoma)(シルル紀)

- エオカルシノソーマ[60]属 Eocarcinosoma(オルドビス紀)

- (属)Eusarcana(=Eusarcus, パラカルシノソーマ[60] Paracarcinosoma)(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- リノカルシノソーマ[60]属 Rhinocarcinosoma(シルル紀)

- ハリウデウミサソリ科[6] Mixopteridae(=Lanarkopteridae)(シルル紀)

- ハラビロウミサソリ科[6] Carcinosomatidae(オルドビス紀 - デボン紀)

- (上科)‘Waeringopteroidea’(正式記載がなされていない[4])(オルドビス紀 - デボン紀)

- (属)Grossopterus(デボン紀)

- (属)Orcanopterus(オルドビス紀)

- (属)Waeringopterus(シルル紀)

- トゲウミサソリ上科[6] Adelophthalmoidea(デボン紀 - ペルム紀)

- トゲウミサソリ科[6] Adelophthalmidae

- (属)Adelopthalmus(=Lepidoderma, Anthraconectes, Polyzosternites, Glyptoscorpius)(デボン紀 - ペルム紀)

- (属)Bassipterus(シルル紀)

- (属)Eysyslopterus(シルル紀)

- (属)Nanahughmilleria(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- (属)Parahughmilleria(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- (属)Pittsfordipterus(シルル紀)

- トゲウミサソリ科[6] Adelophthalmidae

- プテリゴトゥス上科 Pterygotioidea(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- ミラーウミサソリ科[6] Hughmilleriidae(シルル紀)

- スリモニア科 Slimonidae(シルル紀)

- ダイオウウミサソリ科[6] Pterygotidae(=イェーケルウミサソリ科[6] Jaekelopteridae)(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- アキュティラムス(アクチラムス)属 Acutiramus(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- シウルコプテルス属 Ciurcopterus(シルル紀)

- エレトプテルス(エレットプテルス[60])属 Erettopterus(=Truncatiramus)(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- イェーケロプテルス(ジェケロプテルス[60]/ヤエケロプテルス[71])属 Jaekelopterus(デボン紀)

- ネクロガンマルス属 Necrogammarus(シルル紀)

- プテリゴトゥス(プテリゴートゥス[71])属 Pterygotus(=Curviramus)(シルル紀 - デボン紀)

- カルシノソーマ上科 Carcinosomatoidea(=ハリウデウミサソリ上科[6] Mixopteroidea)(オルドビス紀 - デボン紀)

- オニコプテレラ上科 Onychopterelloidea(オルドビス紀 - シルル紀)

- (上位分類未定)

- (属)Dorfopterus(デボン紀)

- (種)?Dolichopterus asperatus(デボン紀)

- (種)?Dolichopterus bulbosus(デボン紀)

- (種)?Dolichopterus herkimerensis(シルル紀)

- (種)?Eurypterus loi(ウミサソリでない可能性がある[4])(シルル紀)

- (種)?Eurypterus podolicus(シルル紀)

- (種)?Eurypterus satpaevi(石炭紀)

- (種)?Eurypterus styliformis(ウミサソリでない可能性がある[4])(シルル紀)

- (種)?Eurypterus tschernyschevi(石炭紀)

- (種)?Eurypterus yangi(ウミサソリでない可能性がある[4])(シルル紀)

- (属)Holmipterus(シルル紀)

- (種)?Nanahughmilleria lanceolata(=Eurypterus chartarius, Eurypterus linearis)(シルル紀)

- (種)?Salteropterus longilabium(シルル紀)

- (種)?Stylonurus perspicillum(デボン紀)

- (属)Unionopterus(石炭紀)

- アシナガウミサソリ亜目[6] Stylonurina Diener, 1924(=Woodwardopterina, Hibbertopterina)(オルドビス紀 - ペルム紀)

脚注[編集]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lamsdell, James C.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Liu, Huaibao P.; Witzke, Brian J.; McKay, Robert M. (2015-09-01). “The oldest described eurypterid: a giant Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) megalograptid from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa” (英語). BMC Evolutionary Biology 15 (1). doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0443-9. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 4556007. PMID 26324341.

- ^ a b c d Poschmann, Markus J.; Rozefelds, Andrew (2021-11-30). “The last eurypterid – a southern high-latitude record of sweep-feeding sea scorpion from Australia constrains the timing of their extinction”. Historical Biology 0 (0): 1–11. doi:10.1080/08912963.2021.1998033. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ^ “Gigantostraca Haeckel 1866”. (official website). Nomina circumscribentia insectorum (World Wide Web electronic database). 2010年4月15日閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2020. A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives. In World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern, online at http://wsc.nmbe.ch, version 20.5, accessed on 28 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d 小野展嗣「海の中に棲む巨大なサソリ」『クモ学 摩訶不思議な八本足の世界』東海大学出版会、2002年、105-108頁。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y 小野展嗣「ウミサソリ綱 Class Eurypteria」「鋏角亜門分類表」石川良輔編『節足動物の多様性と系統』〈バイオディバーシティ・シリーズ〉6、岩槻邦男・馬渡峻輔監修、裳華房、2008年、134-136, 410-420頁。

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Lamsdell, James (2011) (英語). The eurypterid Stoermeropterus conicus from the lower Silurian of the Pentland Hills, Scotland.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x A., Dunlop, Jason; C., Lamsdell, James (2017). “Segmentation and tagmosis in Chelicerata” (英語). Arthropod Structure & Development 46 (3). ISSN 1467-8039.

- ^ a b c Tetlie, O. Erik (2007-09-03). “Distribution and dispersal history of Eurypterida (Chelicerata)” (英語). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 252 (3): 557–574. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.011. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ a b Braddy, Simon J; Poschmann, Markus; Tetlie, O. Erik (2008-02-23). “Giant claw reveals the largest ever arthropod”. Biology Letters 4 (1): 106–109. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0491. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 2412931. PMID 18029297.

- ^ “Eurypterus - definition, etymology and usage, examples and related words”. www.finedictionary.com. 2020年11月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b “eurypterid | Origin and meaning of eurypterid by Online Etymology Dictionary” (英語). www.etymonline.com. 2020年11月26日閲覧。

- ^ “Definition of EURYPTERIDA” (英語). www.merriam-webster.com. 2020年11月26日閲覧。

- ^ 文部省・日本動物学会編「動物分類名」『学術用語集 動物学編(増訂版)』丸善、1988年、1060-1100頁。

- ^ “Distribution and dispersal history of Eurypterida (Chelicerata)” (英語). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 252 (3-4): 557–574. (2007-09-03). doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.011. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ a b c d e f Lamsdell, James C.; Braddy, Simon J. (2010-04-23). “Cope's Rule and Romer's theory: patterns of diversity and gigantism in eurypterids and Palaeozoic vertebrates” (英語). Biology Letters 6 (2): 265–269. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0700. ISSN 1744-9561. PMID 19828493.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lamsdell, James C. (2013-01-01). “Revised systematics of Palaeozoic ‘horseshoe crabs’ and the myth of monophyletic Xiphosura” (英語). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 167 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00874.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schoenemann, Brigitte; Poschmann, Markus; Clarkson, Euan N. K. (2019-11-28). “Insights into the 400 million-year-old eyes of giant sea scorpions (Eurypterida) suggest the structure of Palaeozoic compound eyes” (英語). Scientific Reports 9 (1): 17797. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53590-8. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Tollerton, V. P. (1989). Morphology, taxonomy, and classification of the order Eurypterida, Burmeister, 1843. doi:10.1017/S0022336000041275.

- ^ a b Tetlie, O. Erik; Brandt, Danita S.; Briggs, Derek E. G. (2008-08-11). “Ecdysis in sea scorpions (Chelicerata: Eurypterida)” (英語). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 265 (3): 182–194. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.05.008. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ a b c d e Clarke, John Mason; Ruedemann, Rudolf (1912). The Eurypterida of New York. Albany,: New York State Education Department,

- ^ a b Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1964). “A Synopsis of the Family Pterygotidae Clarke and Ruedemann, 1912 (Eurypterida)”. Journal of Paleontology 38 (2): 331–361. ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ a b c d e f Selden, Paul A. (1981). “Functional morphology of the prosoma of Baltoeurypterus tetragonophthalmus (Fischer) (Chelicerata: Eurypterida)” (英語). Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences 72 (1): 9–48. doi:10.1017/S0263593300003217. ISSN 0263-5933.

- ^ Plotnick, Roy E.; Bicknell, Russell D. C. (2022-09). “The Eurypterid Endostoma and Its Homology with Other Chelicerate Structures”. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History 63 (2): 91–109. doi:10.3374/014.063.0202. ISSN 0079-032X.

- ^ a b Bicknell, Russell D. C.; Kenny, Katrina; Plotnick, Roy E. (2023-11-20) (英語). Ex vivo three-dimensional reconstruction of Acutiramus : a giant pterygotid sea scorpion (American Museum novitates, no. 4004). ISSN 0003-0082.

- ^ a b Selden PA. 1984. Autecology of Silurian eurypterids. Spec. Pap. Palaeontol. 32, 39–54.

- ^ a b c d e Tetlie, O. Erik; Briggs, Derek E. G. (2009). “The origin of pterygotid eurypterids (Chelicerata: Eurypterida)” (英語). Palaeontology 52 (5): 1141–1148. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00907.x. ISSN 1475-4983.

- ^ a b c Hughes, Emily S.; Lamsdell, James C. (2020). “Discerning the diets of sweep-feeding eurypterids: assessing the importance of prey size to survivorship across the Late Devonian mass extinction in a phylogenetic context” (英語). Paleobiology: 1–13. doi:10.1017/pab.2020.18. ISSN 0094-8373.

- ^ Haug, Carolin (2020-08-13). “The evolution of feeding within Euchelicerata: data from the fossil groups Eurypterida and Trigonotarbida illustrate possible evolutionary pathways” (英語). PeerJ 8: e9696. doi:10.7717/peerj.9696. ISSN 2167-8359.

- ^ a b c d Tetlie, O. Erik; Cuggy, Michael B. (2007-01-01). “Phylogeny of the basal swimming eurypterids (Chelicerata; Eurypterida; Eurypterina)”. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 5 (3): 345–356. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002131. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ a b c d e Lamsdell, James C.; Braddy, Simon J.; Tetlie, O. Erik (2010-03-15). “The systematics and phylogeny of the Stylonurina (Arthropoda: Chelicerata: Eurypterida)” (英語). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 8 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1080/14772011003603564. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ Lamsdell, James (2011) (英語). A collection of eurypterids from the Silurian of Lesmahagow collected pre 1900.

- ^ a b Selden, Paul A.; Lamsdell, James C.; Qi, Liu (2015). “An unusual euchelicerate linking horseshoe crabs and eurypterids, from the Lower Devonian (Lochkovian) of Yunnan, China” (英語). Zoologica Scripta 44 (6): 645–652. doi:10.1111/zsc.12124. ISSN 1463-6409.

- ^ a b c d Briggs, D. E. G. (1986-04). “Palaeontology: How did eurypterids swim?” (英語). Nature 320 (6061): 400–400. doi:10.1038/320400a0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kamenz, Carsten; Staude, Andreas; Dunlop, Jason A. (2011-10). “Sperm carriers in Silurian sea scorpions”. Die Naturwissenschaften 98 (10): 889–896. doi:10.1007/s00114-011-0841-9. ISSN 1432-1904. PMID 21892606.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lamsdell, James C.; Hoşgör, İzzet; Selden, Paul A. (2013-01). “A new Ordovician eurypterid (Arthropoda: Chelicerata) from southeast Turkey: Evidence for a cryptic Ordovician record of Eurypterida” (英語). Gondwana Research 23 (1): 354–366. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2012.04.006.

- ^ a b c d Lamsdell, James C.; Selden, Paul A. (2013-05-10). “Babes in the wood – a unique window into sea scorpion ontogeny”. BMC Evolutionary Biology 13 (1): 98. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-98. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 3679797. PMID 23663507.

- ^ a b Braddy, SIMON J.; Dunlop, JASON A. (1997-08-01). “The functional morphology of mating in the Silurian eurypterid,Baltoeurypterus tetragonophthalmus(Fischer, 1839)” (英語). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 120 (4): 435–461. doi:10.1006/zjls.1997.0093. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ James, Lamsdell, (2014-05-31) (英語). Selectivity in the evolution of Palaeozoic arthropod groups, with focus on mass extinctions and radiations: a phylogenetic approach.

- ^ a b Braddy, Simon (1997). “The functional morphology of mating in the Silurian eurypterid, Baltoeurypterus tetragonophthalmus (Fischer, 1839)” (英語). Zoological Journal of the ….

- ^ a b c d Waterston, C.D. 1975: Gill structure in the Lower Devonian eurypterid Tarsopterella scotica. Fossils and Strata 4,241-245.

- ^ a b c d e f g MANNING, P. L., DUNLOP, J. A. 1995. The respiratory organs of eurypterids. Palaeontology, 38, 2, 287–297.

- ^ a b c Braddy, Simon J.; Aldridge, Richard J.; Gabbott, Sarah E.; Theron, Johannes N. (1999). “Lamellate book-gills in a late Ordovician eurypterid from the Soom Shale, South Africa: support for a eurypterid-scorpion clade” (英語). Lethaia 32 (1): 72–74. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1999.tb00582.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lamsdell, James C.; McCoy, Victoria E.; Perron-Feller, Opal A.; Hopkins, Melanie J. (2020-09-10). “Air Breathing in an Exceptionally Preserved 340-Million-Year-Old Sea Scorpion” (English). Current Biology 0 (0). doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.08.034. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 32916114.

- ^ Laurie, Malcolm (1895/ed). “XXIV.—The Anatomy and Relations of the Eurypteridæ” (英語). Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 37 (2): 509–528. doi:10.1017/S0080456800032713. ISSN 2053-5945.

- ^ Moore, P. Fitzgerald (1941/02). “On Gill-like Structures in the Eurypterida” (英語). Geological Magazine 78 (1): 62–70. doi:10.1017/S0016756800071727. ISSN 1469-5081.

- ^ “Eurypterid respiration” (英語). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences 309 (1138): 219–226. (1985-04-02). doi:10.1098/rstb.1985.0081. ISSN 0080-4622.

- ^ a b Whyte, Martin A. (2005-12). “A gigantic fossil arthropod trackway” (英語). Nature 438 (7068): 576–576. doi:10.1038/438576a. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Anderson, Ross P.; McCoy, Victoria E.; McNamara, Maria E.; Briggs, Derek E. G. (2014-07-31). “What big eyes you have: the ecological role of giant pterygotid eurypterids”. Biology Letters 10 (7): 20140412. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2014.0412. PMC 4126633. PMID 25009243.

- ^ McCoy, Victoria E.; Lamsdell, James C.; Poschmann, Markus; Anderson, Ross P.; Briggs, Derek E. G. (2015-8). “All the better to see you with: eyes and claws reveal the evolution of divergent ecological roles in giant pterygotid eurypterids”. Biology Letters 11 (8). doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0564. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 4571687. PMID 26289442.

- ^ King, Olivia Anne; Miller, Randall F.; Stimson, Matt Ryan (2017-02-08). “Ichnology of the Devonian (Emsian) Campbellton Formation, New Brunswick, Canada”. Atlantic Geology 53: 001–015. doi:10.4138/atlgeol.2017.001. ISSN 1718-7885.

- ^ Vrazo, Matthew B.; Ciurca, Samuel J. (2017). “New trace fossil evidence for eurypterid swimming behaviour” (英語). Palaeontology 61 (2): 235–252. doi:10.1111/pala.12336. ISSN 1475-4983.

- ^ Plotnick, Roy E. (1985/ed). “Lift based mechanisms for swimming in eurypterids and portunid crabs” (英語). Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 76 (2-3): 325–337. doi:10.1017/S0263593300010543. ISSN 1755-6929.

- ^ a b Woodward, Henry (1866). A monograph of the British fossil Crustacea, belonging to the order Merostomata.. London,: Printed for the Palæontographical Society,. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.53733

- ^ Ruedemann, John Mason Clarke and Rudolf. The Eurypterida of New York

- ^ Heymons, R. (1901年1月1日). “Die Entwicklungsgeschichte der Scolopender” (ドイツ語). www.schweizerbart.de. 2020年11月26日閲覧。

- ^ a b Weygoldt, P.; Paulus, H. F. (1979). “Untersuchungen zur Morphologie, Taxonomie und Phylogenie der Chelicerata1 II. Cladogramme und die Entfaltung der Chelicerata” (英語). Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 17 (3): 177–200. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.1979.tb00699.x. ISSN 1439-0469.

- ^ Shultz, Jeffrey W. (1990). “Evolutionary Morphology and Phylogeny of Araghnida” (英語). Cladistics 6 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1990.tb00523.x. ISSN 1096-0031.

- ^ Shultz, Jeffrey W. (2007-06-01). “A phylogenetic analysis of the arachnid orders based on morphological characters” (英語). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 150 (2): 221–265. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00284.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z ぞわぞわした生きものたち: 古生代の巨大節足動物. 金子隆一. ソフトバンククリエイティブ. (2012.3). ISBN 978-4-7973-4411-0. OCLC 816905375

- ^ Marshall, David J.; Lamsdell, James C.; Shpinev, Evgeniy; Braddy, Simon J. (2014). “A diverse chasmataspidid (Arthropoda: Chelicerata) fauna from the Early Devonian (Lochkovian) of Siberia” (英語). Palaeontology 57 (3): 631–655. doi:10.1111/pala.12080. ISSN 1475-4983.

- ^ Lamsdell, James C.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Liu, Huaibao P.; Witzke, Brian J.; McKay, Robert M. (2015-10). “A new Ordovician arthropod from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa (USA) reveals the ground plan of eurypterids and chasmataspidids” (英語). The Science of Nature 102 (9-10): 63. doi:10.1007/s00114-015-1312-5. ISSN 0028-1042.

- ^ Lamsdell, James C. (2016-03). Zhang, Xi-Guang. ed. “Horseshoe crab phylogeny and independent colonizations of fresh water: ecological invasion as a driver for morphological innovation” (英語). Palaeontology 59 (2): 181–194. doi:10.1111/pala.12220.

- ^ Dunlop, Jason (1998) (英語). The origins of tetrapulmonate book lungs and their significance for chelicerate phylogeny.

- ^ Weygoldt, Peter (2018年). “Current views on chelicerate phylogeny—A tribute to Peter Weygoldt” (英語). 2018年11月9日閲覧。

- ^ Howard, Richard J.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Legg, David A.; Pisani, Davide; Lozano-Fernandez, Jesus (2019-03). “Exploring the evolution and terrestrialization of scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones) with rocks and clocks” (英語). Organisms Diversity & Evolution 19 (1): 71–86. doi:10.1007/s13127-019-00390-7. ISSN 1439-6092.

- ^ Garwood, Russell J.; Dunlop, Jason (2014-11-13). “Three-dimensional reconstruction and the phylogeny of extinct chelicerate orders” (英語). PeerJ 2: e641. doi:10.7717/peerj.641. ISSN 2167-8359.

- ^ a b c Lamsdell, James C.; Selden, Paul A. (2017-01). “From success to persistence: Identifying an evolutionary regime shift in the diverse Paleozoic aquatic arthropod group Eurypterida, driven by the Devonian biotic crisis: CHANGING EVOLUTIONARY REGIMES DURING THE DEVONIAN” (英語). Evolution 71 (1): 95–110. doi:10.1111/evo.13106.

- ^ Plax, Dmitry P.; Lamsdell, James C.; Vrazo, Matthew B.; Barbikov, Dmitry V. (2018-09). “A new genus of eurypterid (Chelicerata, Eurypterida) from the Upper Devonian salt deposits of Belarus” (英語). Journal of Paleontology 92 (5): 838–849. doi:10.1017/jpa.2018.11. ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ a b c 小林快次 (2014) (Japanese). 大昔の生きもの. 東京: ポプラ社. ISBN 978-4-591-14071-0. OCLC 883613863

- ^ a b 田中源吾(Japanese)『とても巨大な絶滅せいぶつ図鑑』世界文化社、東京、2019年。ISBN 978-4-418-19213-7。OCLC 1104794344。

参考文献[編集]

- 内田亨監修『動物系統分類学』 第7巻(中A)「真正蜘蛛類」、中山書店。 :cf. 動物系統分類学(公式ウェブサイト)

- 石川良輔 編『節足動物の多様性と系統』 (6)巻、裳華房〈バイオディバーシティ・シリーズ〉、2008年4月。ISBN 978-4-7853-5829-7。

関連項目[編集]

著名なウミサソリの例:

関連分類群: