Over the past year, Americans have lamented, loudly and publicly, the loss of many of the communal aspects of pre-pandemic life: eating inside restaurants without worry. Going to packed concerts and sporting events. Celebrating holidays and birthdays with lots of loved ones. Often in a quieter voice, Americans have also lamented a slightly different, less communal loss, one that’s trickier to mourn in the middle of a mass-casualty event. Like mani-pedis.

It’s not just mani-pedis, of course. People have yearned for indulgences corporeal and non-, the types of things that America’s puritanical streak warns against even in better times. The list includes a slew of beauty services that are just not the same at home, if they can even be reproduced there: eyebrow threading, balayage, hair braiding, maybe even a syringe of facial filler. Last March, the television host Kelly Ripa ignited a brief outrage conflagration by joking in an Instagram video (filmed from a chair at her cosmetic dermatologist’s office, while he cackled in the background) that the pandemic had given her an “acute Botox deficiency” that might be deadly.

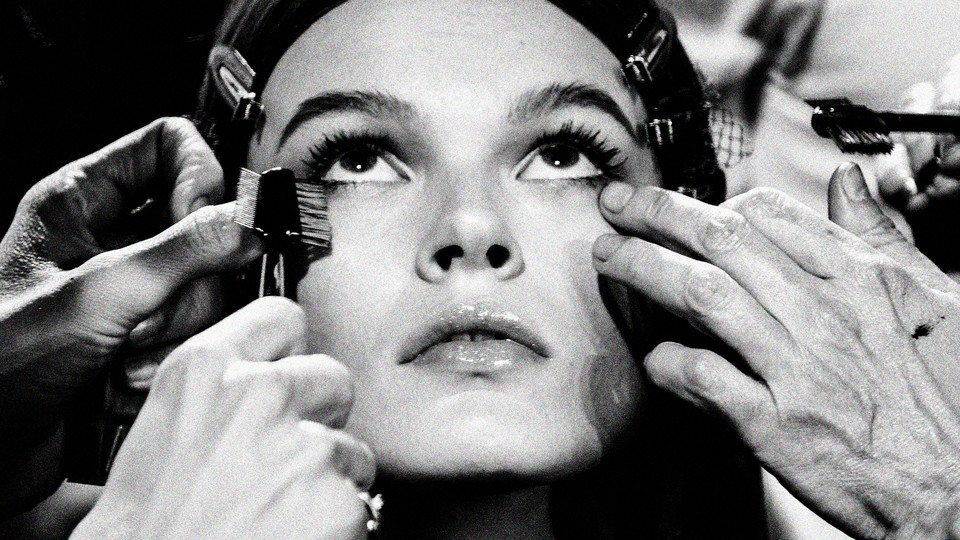

I have remained vigilant against Botox’s particular siren song, but for months I’ve had my own intrusive thoughts about a trained professional manipulating my face or my hair or my hands. Perhaps I could explore the exciting world of eyelash extensions. I could get my first set of acrylics in well over two years, and maybe experiment with lip filler (but, you know, tasteful, not Real Housewives–y). My brain seems to be conjuring these urges from thin air; I had been familiar with all of these services for a long time without much sense that I’d once again want to haul myself to the nail salon every two weeks to get my acrylics filled, let alone that I’d want someone to tinker under the hood of my face. But the idea of changing something about how I look has become thrilling.

When people even tepidly complain about missing cosmetic services during the pandemic, they usually include some nervous disclaimers about how, of course, this year has required innumerable sacrifices far greater than forgoing microblading or Juvederm. Grappling with your personal desires often involves admitting that many of them are sort of dumb, and in the face of the profound suffering of the past year, I have struggled to forgive myself for the puniness of some of mine. At times, just noticing that these are the things my brain wants in the middle of a disaster has felt monstrously selfish and, perhaps worse, profoundly basic.

Slowly, though, the things that have felt so trivial over the past year are beginning to seem more possible—and a bit less trivial. As millions of Americans are vaccinated each day, the beauty industry is poised for an unprecedented summer boom. People are already filling up the appointment books at salons and spas, preparing for a world in which being seen is once again a regular part of the human experience. Americans are ready to look hot again. They are ready to go out. And along with sparkly nails and plump lips, beauty services seem to be offering exactly what so many people have been craving after a year of self-abnegation: a first taste of post-pandemic comfort and a modicum of control over how they enter the future.

People tend to express and affirm their identity through their appearance; feeling as though you don’t look like you anymore can be stressful and destabilizing, even if it’s not literally life-and-death. When most businesses shut down last spring, demand for beauty services didn’t disappear, says Danielle Cohen-Shohet, the CEO and co-founder of GlossGenius, a beauty-industry bookings-and-payments platform. “People who were really desperate were contacting stylists who, for the very first time, were starting to do house calls,” Cohen-Shohet told me. Sign-ups for her company’s software increased dramatically in the first several months of the pandemic, as laid-off providers went solo or businesses updated their antiquated systems in anticipation of contact-tracing protocols.

Bookings surged once salons and spas began to reopen in many parts of the country last summer, Cohen-Shohet said. Then the vaccines arrived, and everything exploded. As doses have been doled out and more good news about efficacy and supply has rolled in, more people have started to see a near future with a few more options. GlossGenius’s internal data show bookings nationwide up more than 20 percent since the beginning of the year, even though that’s usually a period when the industry is on a postholiday downswing.

At Tenoverten, a Manhattan-based group of nail salons, the owners are taking things slowly—only one of its six locations has reopened so far—but evidence of pent-up demand for its services, which include eyebrow maintenance and hair removal, is clear. “All of a sudden, you’ll see a name pop up on the schedule that you haven’t seen for over a year,” Nadine Abramcyk, Tenoverten’s co-founder, told me. “And it’s somebody who’s coming in and doing every single service they could possibly do.” Friends have begun to return in twos or threes, which was a big part of the company’s business before the pandemic. And people are now booking appointments well in advance—a welcome change from before the vaccines, Abramcyk said, when most clients would get bold and talk themselves into booking something short and same-day.

The situation is similar at Plump, which offers cosmetic injectables and other high-tech skin-care services in New York and Miami. “We’re slammed, like fully booked,” Richelle Oslinker, the company’s head of operations, told me. “We’re projecting our busiest summer yet.” To meet the demand, the company is adding more staff. One recently hired injector’s first month of appointments filled up almost immediately, Oslinker said, without any of the marketing and patience that is usually necessary to acquaint clients with a new provider’s skills.

In a very difficult climate for many consumer-facing businesses, the beauty industry is one of a relatively few spaces in which near-term expansion beyond pre-pandemic levels of demand seems possible. Oslinker said Plump is scouting real estate for new locations. Tenoverten, too, has begun to consider not just reopening the rest of its locations, but also moving some of them into larger spaces, or opening new salons entirely, according to Abramcyk. Some of these businesses have more working in their favor than others—providers at the high end of the market, for example, have a clientele with abundant disposable income, which means they serve the subset of people least likely to have had their life and finances shattered by the pandemic. But helpful, too, is the commonality of the desires the industry both promotes and serves—Botox and skin lasers might be most readily associated with a particular type of effete urban elite, but beauty services have a very wide range of prices, and they attract all kinds of customers. Cohen-Shohet said that as salons and spas reopened, demand came back the strongest and fastest in politically redder areas. Now it’s back pretty much everywhere.

Wanting to exert some control over your appearance is, as it turns out, a pretty universal impulse. For Amanda Mitchell, a journalist who covers the beauty industry for publications such as Allure and Marie Claire, the urge to get a little Botox is relatable—not only is she feeling it herself, but she’s noticing it in friends. “In the last three months, I’ve had more people come to me with curiosity about it,” says Mitchell, who has used Botox in the past. These friends had never shown interest before, but a combination of boredom, anxiety, and hope seemed to have opened their mind. Catastrophes have a way of doing that to people; research suggests that extreme stress makes people more likely to significantly change their appearance. The classic example is cutting post-breakup bangs, but maybe surviving a global pandemic requires something subdermal.

GlossGenius has noticed this tendency in its data. Not only are people booking more appointments overall in 2021, but they are booking more services at once, and much of that growth is from those who are trying things they’ve never scheduled before. (Tips, too, have gone up throughout the pandemic, by an average of more than 15 percent. People “didn’t realize what they had until they didn’t have it,” Cohen-Shohet said.)

Mitchell has also been contemplating the plethora of previously unexplored physical changes available to her, and why she might want to make them. Part of it, she told me, is not that deep—she hasn’t seen her larger social circle in a long time, and impressing people by being hot is fun. Feeling hot is fun. But below that is another layer of desire. “I don’t want to get rid of the past year entirely. It made me a deeper and better person, I think, or at least a little bit more of an empathetic one,” Mitchell said. “I just really don’t want to physically show how hard the year was on my body. I don’t want the world to see that.”

How we shape and maintain our appearance is a social task—our bodies do so much communicating on our behalf, and being seen by people we care about is a fundamental part of our mental health. For many people, 2020 lacked positive, social, in-person opportunities to have their humanity reflected back at them, a stress that eventually became visible in their stooped shoulders or thinning hair or dry skin. Those moments of connection are returning, little by little, along with many of the other joys that make up a human life. For people anticipating a return to the physical world, being able to stake some claim on how they will do it is a comfort, after a year in which any particular individual controlled so little of their fate.

The physical results of these procedures may indeed be trivial—anything that includes buying a particular number of new eyelashes is trivial by definition. But beauty services don’t just promise aesthetic transformation. Having your skin treated or your hair dyed or your nails painted is a small, safe intimacy that was made treacherous by a deadly respiratory disease. Now that I’m fully vaccinated, maybe it’s not the eyelash extensions that sound so exciting, but the opportunity to be in a small room with a careful stranger without worrying about what’s in the air, and to pay someone else to help me do something while spa music plays in the background, after a year of doing so much by myself, and poorly.

Maybe it’s both. I’d better get the new lashes to find out.