Councils forced to overspend by £600m to protect vulnerable children as cuts push services to 'breaking point'

'Unless we see quick action from the Government to fill the black hole in funding for social care vulnerable children and families will be put at risk'

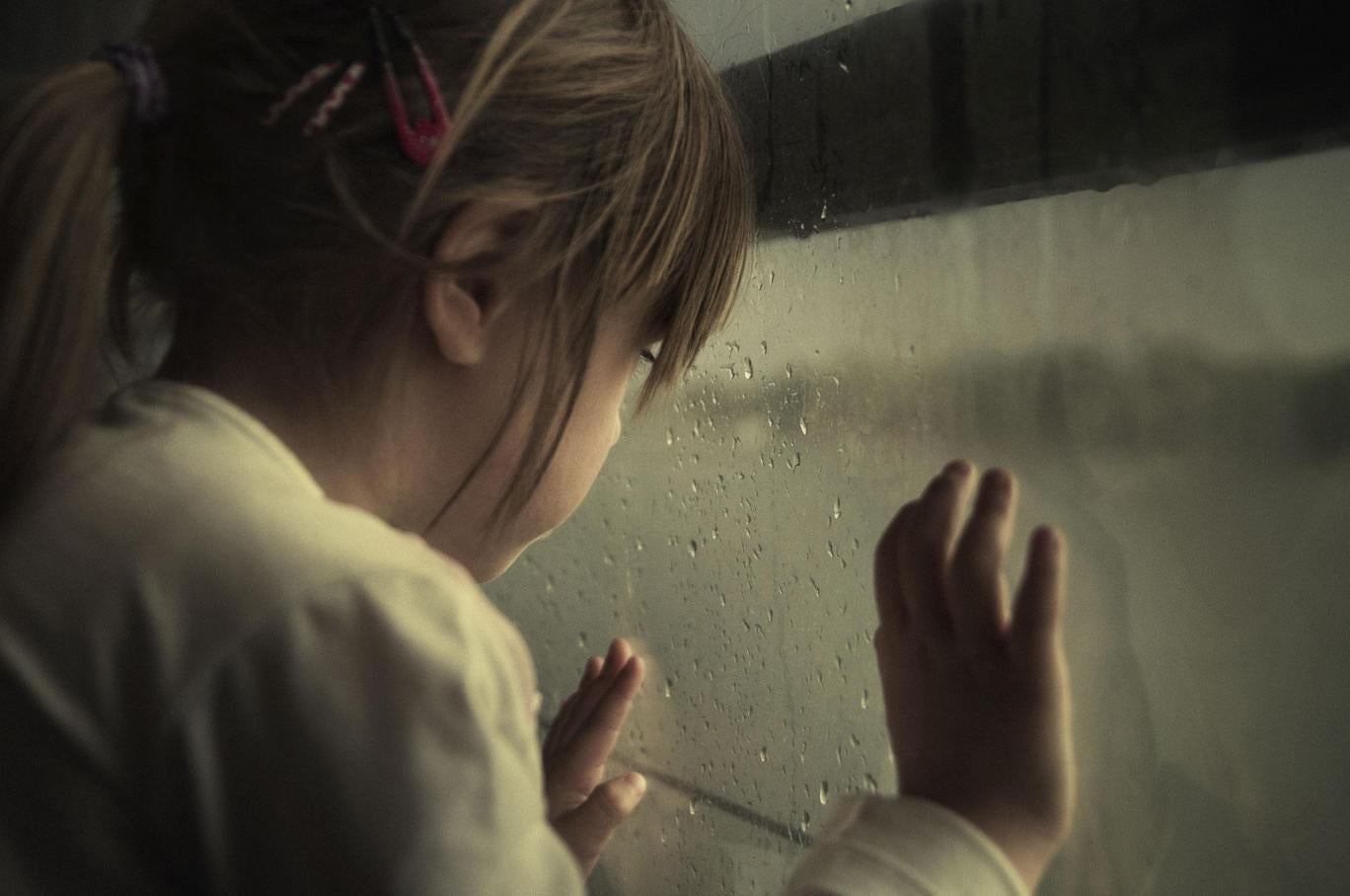

Funding cuts have pushed children’s social services to “breaking point” with action only being taken to protect youngsters once they are at imminent risk of harm, council leaders warn today.

Painting a damning picture of the state of children’s social care, a report from the Local Government Association (LGA) says cuts to early intervention services have led to an “unprecedented surge” in demand for urgent child protection support.

The analysis reveals that three-quarters of English councils exceeded their budgets for children’s services last year, totalling a £605m overspend, while the number of young people subject to child protection enquires increased by 140 per cent – to 170,000 – in the past decade.

Youngsters at risk of neglect and abuse in their homes are falling through the net, experts warned, leading to a growing number of cases in which social services intervene once the “damage has already been done”.

Council leaders are now warning that the pressures facing children’s services are rapidly becoming “unsustainable”, with a £2bn funding gap expected by 2020, while social workers have said the situation has got to the point where they are turning away children at risk.

Richard Watts, chair of the LGA, told The Independent that cuts to early prevention services have led to growing numbers of families reaching crisis point, which often involves children being subject to neglect and domestic violence.

“Local councils have seen massive cuts to budgets over last seven years, with cuts to a lot of things like youth and children services that would play a role in stopping families getting into crisis,” said Mr Watts.

“Anecdotally, the overwhelming increase in cases coming forward are to do with neglect and also a big increase in domestic violence. In my own authority, in three out of four cases coming to the attention of child protection services there is a domestic violence element to the case.

“We are seeing unprecedented pressure on families for a whole range of reasons. No doubt they are struggling at the moment and its clearly having a knock-on impact in the demand on the child. Massive cuts to those services that kept people’s heads above water have meant that more families are finding their way through to even more expensive child protection services.

“Councils are doing their best in very difficult circumstances but services are at breaking point and unless we see quick action from the Government to fill the black hole in funding for social care vulnerable children and families will be put at risk.”

A separate analysis published today by the County Councils Network (CCN) reveals that pressure on children’s service has risen most dramatically in rural councils, warning that they receive half the money urban councils get to deliver these services.

It states that county authorities already receive £292 less per head than the average council in London, with services to protect vulnerable children in large parts of the country therefore seeing a dramatic “unfunded” spike in demand.

The damning indictments from council leaders come after an inquiry by the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Children (APPGC) found earlier this year that nearly 90 per cent of senior council managers across England said they were finding it increasingly difficult to provide children "in need" with the support they require.

The number of child protection plans – which are put in place for those at serious risk of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, or neglect – increased by over 29 per cent between 2010/11 and 2015/16, while over the same period the number of children being taken into care rose by 17 per cent, the inquiry found. Local authority spending power meanwhile decreased by over 20 per cent.

Tim Loughton, chair of the APPGC and former children’s minister, said children’s social services had become confined to “crisis management”, while early intervention in cases of potential child neglect and abuse had declined.

“With all the focus on adult social care, children’s social care is a rather neglected Cinderella service. You’ve got at the highly critical end those kids who are in most need of intervention and are still being looked after, but then you get a whole load who are at the bottom end where neglect is becoming entrenched,” he said.

“In households where parents are struggling to bring up their kids, neglect can become abuse, and the kids fall further and further behind. They develop mental health problems and start displaying those traits at school. That’s what the whole early intervention programme was designed to prevent.

“It’s become all about crisis management rather than proactive planning and intervention where there are parents at risk of being abusive. It’s a false economy not to intervene in cases of potential child neglect early because the bill will be a lot higher later on once damage has been done.”

Last month, it emerged that social workers in the UK are working an average of 64 days of overtime a year, leading care workers associations to warn that overworking increases the risks of child abuse cases such as that involving Baby P.

A study showed as many as 92 per cent of the 100,000 registered social workers in the UK are working an average of 10 hours’ unpaid overtime each week, amounting to approximately 480 hours every year, or 64 days per person.

Tiffany Green, who has been a social worker for eight years in a number of London councils, told The Independent cuts to the services that used to support children who were “on the edge” have led to a growing number needing help from child protection services further down the line.

“There used to be youth centres and targeted youth support in the community. You’d have those young people who were kind of on the edge – they didn’t necessarily meet threshold, but you could refer them onto get intervention and services from these support workers,” she said.

“Now those services aren’t there, so social workers have had to become a lot more scrupulous with what we do. You have to determine who is most needy. As a social worker, you now have to say, ‘Oh, you may not have food, but this family hasn’t had food for two days so I’ve got to give the resource to them and find a different way to help you.’

“There are no longer enough services to act as a buffer to keep social services from being inundated. The loss of services, the welfare reforms, because people have less money, higher stresses – social services then become the answer to all.”

Dr Ruth Allen, CEO of the British Association of Social Workers (BASW), said social workers were coming under increased strain and urged the Government to meet with local councils and social workers to abate the situation.

“The volume of referrals, high thresholds and the complexity of need and support for children, families and adults is ever increasing. BASW members are reporting high caseloads, finite resources and not having enough quality time to undertake direct work with the children and families they serve,“ she said.

“We urge the Government to meet collectively with BASW, the LGA and other key organisations to discuss how we put vulnerable children, families and adults at the heart of government funding policy and invest in good quality social work and the social care workforce.”

Government funding for the Early Intervention Grant, which was introduced in 2010 and pulled together a number of different funding streams including support for children’s centres and family services, has been cut by almost £500m since 2013 – and is projected to drop by a further £183m by 2020.

During this time, councils have seen the closure of 365 children’s centres and 603 youth centres.

Jo Casebourne, chief executive of the Early Intervention Foundation, said: “At a time of shrinking budgets and increasing demand, it is critical that local authorities are able to use evidence to ensure scarce resources are directed towards interventions with the greatest chance of success.

“Our research highlights the evidence that early intervention can be effective, for example, in reducing child abuse and neglect or improving children’s behaviour and mental health.

“These positive outcomes reduce the hardship those children and their families experience, and help to reduce the demand on more expensive services down the line.”

When contacted for comment, a Government spokesperson said: “Every single child should receive the same high-quality care, support and protection, no matter where they live. Councils will receive more than £200bn for local services, including children’s social care, up to 2020.

“This is part of a historic four-year settlement which means councils can plan ahead with certainty.

“Councils are doing excellent work, spending more nearly £8bn in total last year on children’s social care, but we want to help them make sure they do even more. That’s why we set up the our £200m Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme to help them develop new and better ways of delivering these services.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies