the U-234 U-234 Japan's A=Bomb

At first, the men on the submarine thought it was a trick. The radio message from the German High Command told them the war was over; they were to surrender to the nearest Allied authorities.

and

U23

The U-234, 294 feet long and 22,000 tons fully loaded, was one of the titans of the German undersea fleet; it had surfaced briefly somewhere in the mid Atlantic at this pivotal moment in its history -- May 10, 1945 -- to receive radio messages and find out what was happening in the European war.

No trick: The war in

The mystery of U-234 and its cargo had just begun, however. The boat was en route to

The radio message was so stark, so shocking, Lt. Johann Heinrich Fehler, captain of U-234, wasn't about to take it on face value. He would have to test it out, make sure it was authentic, before deciding what his response would be.

The message, issued under the auspices of Admiral Karl Dönitz, former German U-boat chief elevated to supreme commander after the death of Adolf Hitler, praised all U-boat crews for "fighting like lions" for more than six years and then informed them that the enemy's material superiority had driven Germany to defeat.

"We proudly remember our fallen comrades," Dönitz consoled. "Long live

U-234 immediately submerged. "They are trying to trick us," Fehler speculated, "they" being the enemy --

Fehler knew all about tricks. As an officer aboard the German raider Atlantis, he'd become familiar with the ship's somewhat infamous means of surface deception. The Atlantis would disguise itself as a friendly ship and lure enemy ships to within range of its camouflaged guns before opening fire. The Atlantis had thus bagged 22 Allied ships before it was sunk by the British cruiser,

U-234 sent out a message of its own to a nearby U-boat, in a special code that only captains could send and decipher.

"We have received a very funny message," Fehler radioed. "Have we surrendered? Is it true?"

The reply convinced him the message was no trick. His orders were to surface, to hoist a black flag on U-234's periscope, and to report his position to the Allies.

Not Yet

Fehler was a German officer which meant when he gave orders everybody snapped to But, for whatever reasons, the man who had earned the nick name "Dynamite" for his job of scuttling captured vessels decided to exercise some democracy that day.

Uranium Oxide

He asked for opinions from some of his colleagues in the converted minelayer whose cargo contained enough uranium oxide to blow up two American cities -- 1,235 pounds of it, possibly destined for a Japanese atomic bomb program. But it is likely that nobody knew about the cargo except Fehler. The officers and crew therefore were not thinking of uranium when they replied. "We have enough food to last us for years," remarked the boyish second officer, Lt. Karl Ernst Pfaff. "I think we should go to the

It had momentarily slipped Pfaff’s mind that he was engaged to Fehler's sister-in-law. Fehler laughed. "That is wishful thinking," he told the 22-year-old Berliner who would never be his brother-in-law.

A pattern of responses emerged, the younger men tending to share Pfaff’s compulsion to run from it all while the older ones just wanted to go home to their families and forget the war.

Geography was a major factor in that U-234's position lay at the convergence of four Allied zones established for U-boat surrenders. Fehler could have surrendered to the enemy port of his choice.

The latter would have been risky, Fehler knew, because the Russians -- no admirers of Hitlerite fighting men -- had been expanding naval operations in German waters. Neither he nor anybody on board wished to become a Soviet prisoner.

Picked

Fehler surmised that if they surrendered to

Fehler perceived Americans as "not war faring people, not very military." At worst, he predicted they could be paraded through the streets, showcased so to speak as proof that real, live U boat crew members had been captured , and then sent home.

Fehler decided to turn U-234 into the gentle Americans. But he had to make sure the Canadians didn't get to him first.

U-234 radioed authorities in

Japanese Passengers

The depressed atmosphere inside the black-flag-flying U-boat was disrupted by an incident involving two passengers, Imperial Japanese Navy Lieutenant Commander Hideo Tomonaga, a leading Japanese submarine designer, and Lieutenant Commander Genzo Shoji, an aircraft expert, who had come along to study German weaponry.(Whether they also knew of the atomic cargo remains one of the unsolved mysteries of U-234.)

Fehler explained to the Japanese that he had to surrender because he had to obey his high command just as they would have to follow theirs.

An officer later recalled:

They returned to their bunks where they took Luminol, a very powerful barbiturate, lay down and pulled the curtains and we knew they were killing themselves, and that was their right. They took more than 36 hours to die. Then we buried them at sea, as we would do for any one of our own.

Ulrich Kessler

The passenger list also included German Luftwaffe Lieutenant General Ulrich Kessler, former commander of special bombing and attack wings based in

Kessler, with a monocle over one eye and a perpetual air of arrogance, passed his time reading books and, upon arrival in

But, displaying another, more practical side, Kessler admitted during interrogation that he had intended all along to get off the sub at Argentina -- not an unbelievable story in light of the fact that many top-ranking Germans already had fled to that South American country.

Whether Kessler knew of the atomic cargo remains a mystery today. Researchers find it more likely Kessler, knowing the war was about to be lost, had boarded the sub as a means of escape.

The discrepancy between Fehler's reported and actual course was soon recognized by

One evening as it plowed the seas south of Newfoundland Banks, U-234 spotted a huge searchlight on the horizon. The destroyer Sutton approached and asked U-234 to identify itself. Crew members of the Sutton boarded and took charge, redirecting it to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard where three other U-boats, U-805, U-873 and U-1228, had surrendered within the last few days.

U 873 Type IXD-2 and U 234 Type XB in dock at

News of the surrender of the giant sub with its high-ranking Luftwaffe passengers turned the surrender into a major news event. Reporters swarmed over the Navy Yard and went to sea in a small boat for an earlier view of the prize.

But the big story -- the more than half a ton of uranium oxide on board -- was promptly covered up.

The

Even after the war ended, documents reporting the uranium cargo on U-234 remained classified for the duration of the Cold War as

Researcher Fascinated

Velma Hunt is a retired

Hunt says finding out the truth about the sub's cargo was complicated by looting by drunken American sailors who not only carried away souvenirs but also managed to lose documents that might have provided crucial details about the origins and intended destination of the uranium.

"Captain Fehler," Hunt said, "while complaining about the looting, mentioned he was all the more indignant about it, considering all he had had to do was pull a lever and every mine shaft would have emptied its contents into the ocean." That would have included the uranium, Hunt said.

Hunt said the U-234 and the Sutton may have gone into two ports between the surrender and the arrival at Portsmouth Navy Yard, once in Newfoundland when an American sailor mistakenly shot in the buttocks had to be evacuated for post-surgical treatment, and once again at Casco Bay. The unscheduled landings presented a problem for Ilmerican intelligence personnel, who worried that some cargo might have been off-loaded in the two ports.

The 41 crew members, six officers and nine passengers had been transferred to a Coast Guard vessel at sea. Fehler's arrival was something less than ceremonious.

Raised Ruckus

"He compared the tactics of U.S. Naval personnel to that of gangsters," Gray reported, whereupon an American officer retorted, "That's just what YOU are."

Gray described the crew as looking well-fed but wearing the most nondescript uniforms he'd ever seen on a German sub crew. All were dirty, he said, and each carried a small leather bag, canteen, and blankets.

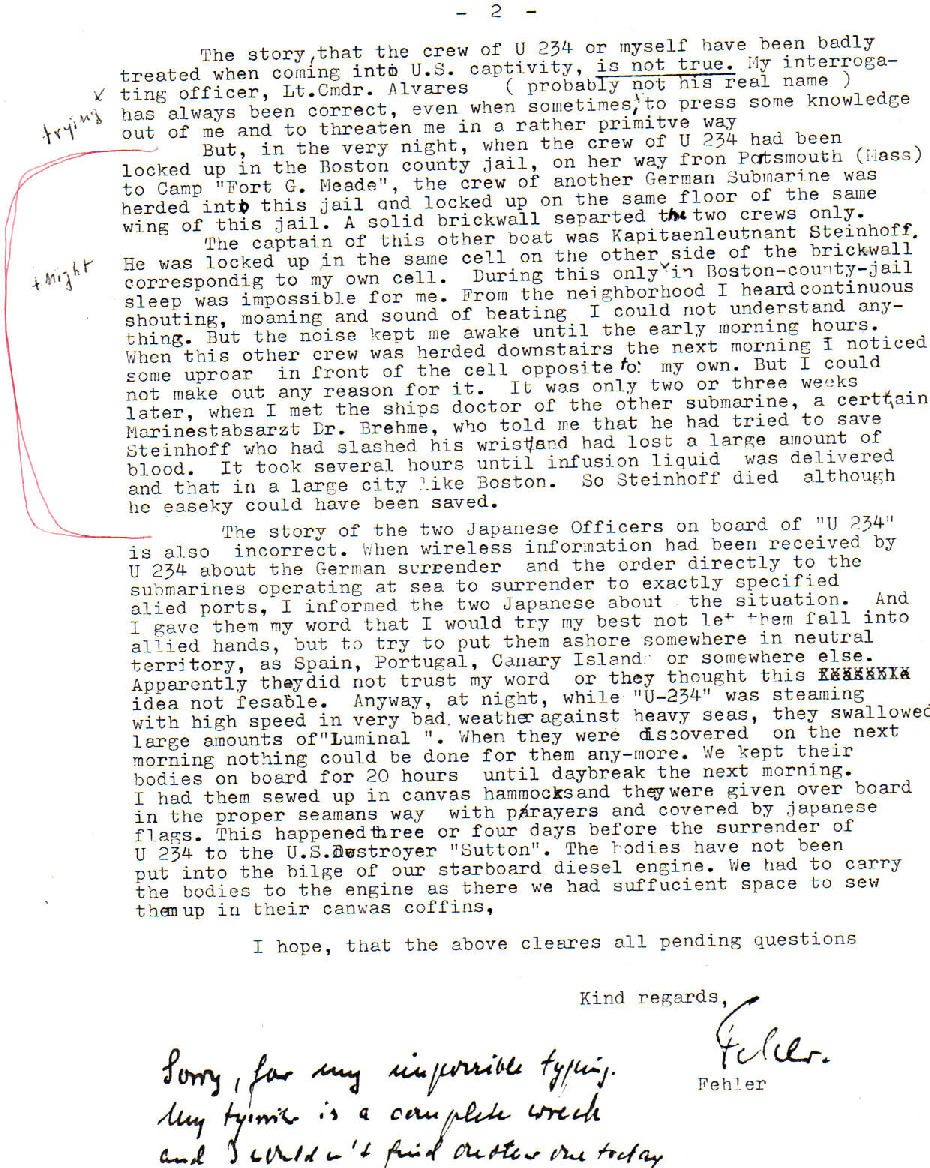

The men of U-234 joined the officers and crews of the three subs that preceded them, as prisoners in the custody of the U.S. Navy. While at the Charles Street Jail in

U-234 officers were taken to

Pfaff was ordered to oversee the opening of a metal container. The reluctant welder with the cutting torch pleaded with Pfaff not to let him die because he had a family. The military watchdogs stood back, out of harm's way.

"He begged me not to let both of us get blown up," Pfaff said, I'and I assured him that I too did not want to die young. Why would these boxes be booby trapped? They were on their way to our ally (

When they saw that it was safe, the military came out of hiding. Pfaff said he was then asked to open the boxes -- little cigar-box shaped boxes, he recalled -- that contained the uranium oxide.

A "tall, skinny fellow" wearing an "Eillot Ness" hat -- that is, a hat fashionable in the 1930s and 40s -- appeared. The only civilian in the room, he went about supervising the opening of the boxes. Who is that? Pfaff asked. Oppenheimer, somebody said.

"I had no earthly idea who Oppenheimer was," Pfaff said. But later, when the war finally ended, Pfaff, in a detention center in Louisiana, read news reports about atomic physicist J. Robert' Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos laboratory where the design and building of the first atomic bomb took place.

"I didn't know for sure that it was Oppenheimer in there," Pfaff said. "I had to take this man's word."

Japan's A-Bomb

Robert K Wilcox is an historian who has written about

In 1985 Wilcox wrote a book, Japan's Secret War -- Japan's Race Against Time To Build Its : Own Atomic Bomb, that said the listing of 560 kilograms of uranium oxide for the "Jap Army" on U-234's manifest had elicited such concern with the War Department that it was kept from the public and subsequently became a classified document.

The cargo was not officially revealed. But even if it had been, few Americans would have understood its significance.

This was three months before the

Wilcox cited the story of the U-234 as evidence that the Japanese may have been close to developing their own atom bomb and would not have hesitated to use it.

As the recent public hand wringing over the Smithsonian's Enola Gay exhibit attests, the issue of whether the

It would appear from the US Unloading Manifest, a dockyard Memorandum and a couple of cablegrams from New Portsmouth naval base that there were ten cases each of 56 kilos of "uranium oxide" on the submarine. This material was contained in gold lined cylinders and was said to be dangerous if opened. It is clear that this was not weapons-grade U-235. There were also eighty small containers described as "U-powder" aboard U-234. This might have been natural uranium processed in a non-critical sub-reactor to a stage where there was sufficient radioactive activity present to warrant a lead container. The United States produced all its own weapons-grade fissionable material. There was more U-235 in store than can be explained after the Hiroshima bomb was dropped. Most probably the surplus resulted from the Hiroshima bomb being detonated by the Exploding Bridge Wire, which would have made the U-235 bomb much more economic in fissionable material. |

Pfaff Comes Back

Lt. Karl Ernst Pfaff was held in prisoner of war centers in

"I had taken a liking to this country and to the American style," Pfaff said, and he immediately began planning his strategy: to return.

He found his way to

'The war was a different part of my Life," Pfaff said in an interview last week, "something people don't understand. When the war was over and we had lost it, I had to do something and start another part of my life. I disappeared from the surface. Nobody, except my close friend Fehler, knew where I was."

Fehler acquired an international reputation for clearing waterways such as the

Pfaff and Fehler lost contact until 1991 when they met for the last time at a U-234 reunion in southern

U-234's reunions, like the reunions of all World War II veterans' groups, are attended by fewer people as the years go by. In 1985, there were 60 crew and wives; in 1991, 40.

This September Pfaff will be the highest officer attending the reunion of U-234

"There aren't many of us left Pfaff, now 72, observed, and excused himself to go out and rake the lawn as he had promised his wife he would.