I am driving down Route 180 in St Louis, Missouri, past empty plazas and vacant shops, down a stretch of road that terminates in an abandoned mall. Yet on this road are promises of wealth: “Loans Up to $10,000”, says one sign. “Advances up to $500” says another. In contrast to the faded retailers surrounding them, these new storefronts are cheerful, decorated with pictures of flowers or gold or the American flag.

This is the alternative economy of payday loans, which has sprung up where the old economy has died.

In St Louis, a payday loan is something which you are either intimately familiar with or completely oblivious to. The locations of payday loan outlets correspond to income: the lower the regional income, the more payday loan centers you will find. The 249 payday lenders in the St Louis metro area are almost entirely absent from wealthy or middle class areas. The outlets supply small loans – usually under $500 – at exorbitant interest rates to be paid off, ideally, with one’s next paycheck.

“You only see them in poor neighborhoods,” says Tishaura Jones, the treasurer of St Louis and an active campaigner to regulate the industry. “They target people who don’t have access to normal banking services or who have low credit scores. It’s very intentional.”

The explosion of payday lending is a recent phenomenon. According to the Better Business Bureau, the number of lenders grew nationally from 2,000 in 1996 to an estimated 22,000 by 2008. In Missouri, there are 958 more payday lenders than there are McDonald’s restaurants, a ratio reflected in most US states. The 2008 economic collapse only increased the outlets’ clientele, particularly in St Louis, which has more unbanked people than any other US city.

“The effects of payday loans on families are tenfold,” explains Jones. “If they can’t pay it back, they have two choices. They can roll it over to another one and then pay more, or they can try to pay it back – but then something else goes unpaid. They can’t get out. They’re in a constant cycle of debt. Fifty percent of families are in liquid-asset poverty, which means they lack any sort of savings. The average amount that a family lacks for what they call liquid-asset poverty is $400. It seems insignificant, but $400 can mean life or death.”

Jones was a supporter of a failed 2012 Missouri ballot initiative to cap payday loan interest rates at 36%. Currently, interest rates are uncapped and have known to be as high as 1,900%, with rates of 200%-500% common. Some borrowers seek payday loans for emergencies, but many use them to pay for necessities like food and rent – a consequence of a low-wage economy. Payday loan outlets frequently set up shop on military bases and nursing homes – sites which guarantee clienteles with low fixed incomes.

“You need two things to get a payday loan,” says Erich Vieth, a St Louis lawyer who specializes in prosecuting payday lenders. “A paycheck and a pulse.”

Unlike traditional loans, payday loans are free from underwriting or interest regulation. The result, according to Vieth, is that “payday lenders are charging interest rates higher than what people charged when they were arrested for loan sharking decades ago”.

Since 2006, Vieth and his partners at St Louis’s Campbell Law firm have sued a number of payday lenders, including Advance America and QuickCash. Part of the problem, he says, is the legal process itself. Payday loan lenders require borrowers to sign a clause stating that all legal action will be handled by an arbitrator appointed by the payday loan company, rendering class action lawsuits extremely difficult. Often working on a pro bono basis, Vieth has challenged both the arbitration rule and predatory lending. He notes that payday lenders often garnish wages or drag clients into expensive lawsuits, furthering their debt.

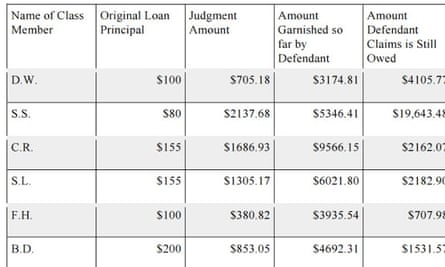

“Here’s a client of ours,” he says, showing me a legal brief. “She borrowed $100. She made one instalment payment, couldn’t pay the rest, and was sued. Since then they’ve collected $3,600 in payments by garnishing her wages. That’s 36 times the hundred bucks she owed. They told her she still owes $3,600 more. The wage garnishments are reducing the debt slower than the high interest, which is 200%. She called her attorney and asked ‘When will I be done paying this?’ And he said: ‘Never.’ It’s indentured servitude. You will never, ever be done.”

Vieth’s client is lucky compared with others mentioned in the case file: one borrowed $80 and now owes the payday lender $19,643.48.

Payday loans do not require a borrower to reveal their financial history, but they do require “references”: names of family and friends who are then harassed by the lender when the borrower cannot pay. According to Vieth, this is not the only underhanded tactic the companies take, particularly given their influence in financing political candidates who then vote to protect the companies’ practices.

He recalls a 2010 public hearing where all seats were filled by low-level payday loan employees, preventing citizens, including himself, from witnessing the proceedings. The employees confirmed to Vieth they were paid to take up space. He notes that the 2012 initiative to cap interest rates failed by a narrow margin – after petitions with signatures were allegedly stolen out of cars and from campaign headquarters, or disqualified for unknown reasons.

Jones, the treasurer, corroborates: “I was contacted by an attorney and told my signature was deemed invalid. I have no clue why. They invalidated a lot of signatures, so it didn’t go on the ballot.”

In Missouri, the momentum to regulate predatory lending has eased. Payday loans are part of the new economic landscape, along with pawn shops, title loan outlets, and rent-to-own furniture stores that stand where retailers selling things once stood.

Poor Americans no longer live check to check: they live loan to loan, with no end in sight.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion