- India

- International

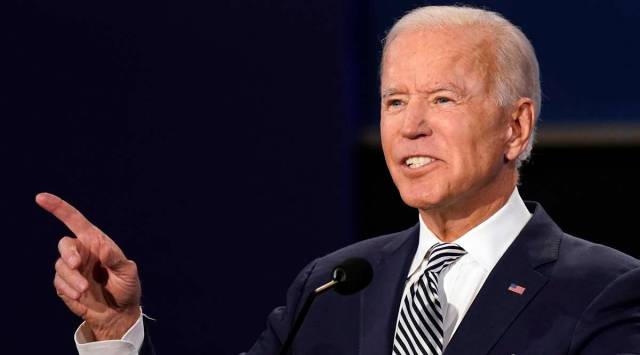

Biden falls short on pledge for US to be the world’s vaccine ‘Arsenal,’ Experts Say

Biden took his first steps to address the vaccine shortage in March, when the White House announced the Merck deal as well as a partnership with Japan, India and Australia aimed at expanding manufacturing capacity.

White House officials say that it is not possible for them to scale up production quickly, in part because of a scarcity of raw materials, and that doing so would take three to five years (File)

White House officials say that it is not possible for them to scale up production quickly, in part because of a scarcity of raw materials, and that doing so would take three to five years (File)President Joe Biden, who has pledged to fight the coronavirus pandemic by making the United States the “arsenal of vaccines” for the world, is under increasing criticism from public health experts, global health advocates and even Democrats in Congress who say he is nowhere near fulfilling his promise.

Biden has either donated or pledged about 600 million vaccine doses to other countries — a small fraction of the 11 billion that experts say are needed to slow the spread of the virus worldwide. His administration has also taken steps to expand COVID-19 vaccine manufacturing in the United States and India, and is supporting production in South Africa and Senegal to expand access to locally produced vaccines in Africa.

But with the administration now recommending booster doses for vaccinated Americans starting next month, outraged public health experts and many Democrats on Capitol Hill are calling on the president to move more aggressively to scale up global manufacturing. In an analysis to be published Thursday, AIDS advocacy group PrEP4All found that the administration had spent less than 1% of the money that Congress appropriated for ramping up COVID-19 countermeasures on expanding vaccine manufacturing.

Congress put a total of $16.05 billion in the American Rescue Plan this year, in two separate tranches, that could be used to procure and manufacture treatments, vaccines and tools for ending the pandemic. But PrEP4All found that all told, the administration had spent $145 million — just $12 million of it from the American Rescue Plan — to expand vaccine manufacturing. The bulk of that went to retrofitting production lines at pharmaceutical giant Merck, which is teaming up with Johnson & Johnson to produce 1 billion vaccine doses starting in early 2022.

White House officials say all the money has been allocated as intended, including $10 billion for “vaccine raw materials, vaccine and other manufacturing capacity, and industrial base expansion.” But they did not respond to repeated questions about whether or how the money has actually been spent. Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., and the chairwoman of the Senate health committee, has also asked for a more detailed accounting, her office said.

On Capitol Hill, 116 Democrats, including Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, have called for putting $34 billion to increase vaccine manufacturing capacity in the upcoming budget reconciliation act. This month, they wrote to the president asking him to endorse the idea but have not gotten a response, said Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi, D-Ill., who is leading the effort in the House.

“This lack of attention to executing a robust vaccination strategy abroad is arguably one of their biggest missteps with regard to COVID,” said Krishnamoorthi, who said he lost three members of his extended family in India to COVID-19.

James Krellenstein, a founder of PrEP4All and the author of its report, was more pointed. “If they don’t change course pretty soon,” he said, “the Biden administration is going to be remembered in terms that the Reagan administration is remembered today in not dealing with the AIDS crisis.”

Addressing the world’s coronavirus vaccine needs is a complicated endeavor, with many layers of challenges. Vaccine makers around the world, including those in Russia, China and India, have predicted a total of 12 billion doses by the end of 2021, according to Duke University’s Global Health Innovation Center, which tracks vaccine manufacturing and publishes the Launch and Scale Speedometer website. Eight months into the year, an estimated 5 billion have been delivered.

Some manufacturers are falling behind. Novavax has had production problems. Johnson & Johnson, which initially planned for 1 billion doses this year, has made slightly more than 103 million, Krellenstein said, citing data from the scientific intelligence firm Airfinity. That is in part because its contract manufacturer, Emergent BioSolutions, ruined up to 15 million doses, prompting the Food and Drug Administration to shutter its Baltimore plant for three months.

If 12 billion doses were indeed produced and equitably distributed by year’s end, the world’s needs could be met. But, the Duke institute wrote, “those are both big ifs.”

Several other countries as well as the United States are already recommending booster shots, which will cut into the supply. And the virus changes shape so rapidly — the highly infectious delta variant is now dominant around the globe — that the vaccines developed last year may soon be outdated, said Dr. Richard Hatchett, chief executive of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, which helps lead the international vaccine effort known as COVAX.

In the short term, poor nations need doses, and Biden is correct when he says the United States has donated more than any other country. The United States has already donated 115 million surplus doses from the nation’s own supply, and has purchased 500 million doses from Pfizer and BioNTech to be distributed through COVAX. With the United States planning for booster shots, one official said, there is no surplus right now.

“Their financial contributions are huge — no other country has pledged as much as the U.S.,” Hatchett said. But, he added, “it’s not to say that they can’t and shouldn’t do more.”

Hatchett said he would like to see a more nuanced discussion of the logistics of not only making vaccines for poor and middle-income nations, but also administering them. The New York Times recently reported that COVAX was having trouble getting those shots into people’s arms. Unused doses are sitting idle on airport tarmacs in poor nations that lack the money and capacity to buy fuel to transport doses to clinics, to train people to give the shots — and to persuade people to take them.

Biden took his first steps to address the vaccine shortage in March, when the White House announced the Merck deal as well as a partnership with Japan, India and Australia aimed at expanding manufacturing capacity. That included a pledge to help Biological E, an Indian manufacturer, produce 1 billion doses by the end of 2022.

A White House official said the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, which is making the investment, “expects to begin disbursing funds within the next several weeks.” The official did not offer specifics, or an amount.

Biden promised in June that the United States would begin an “entirely new effort” to increase vaccine supply and vastly expand manufacturing capacity, most of it in the United States. He also put Jeffrey D. Zients, the White House coronavirus response coordinator, in charge of developing a global strategy. Zients pledged to work with U.S. manufacturers to “vastly increase supply for the rest of the world in a way that also creates jobs here at home.”

But since then, the delta variant has shifted the focus to the new domestic crisis. Dr. Krishna Udayakumar, director of the center at Duke, faulted Biden for pursuing an approach that “continues to be piecemeal” — an assessment echoed by J. Stephen Morrison, a global health expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

“They don’t have a strategy, nor do they have a structure to execute it,” Morrison said.

White House officials say that it is not possible for them to scale up production quickly, in part because of a scarcity of raw materials, and that doing so would take three to five years — an assertion that Dr. Tom Frieden, who directed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention during the Obama-Biden administration, dismissed as “nonsense.”

Frieden, now the president of Resolve to Save Lives, a health nonprofit, pointed to Lonza, a Swiss biotechnology company, which entered into an agreement with vaccine maker Moderna in May 2020, retrofitted its facility in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and was producing vaccine six months later.

“People say, ‘Oh, it’s going to take months,’” Frieden said. “Well, COVID is with us for years. The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago. The second best time is today.”

Frieden and others also want the Biden administration to lean more heavily on Pfizer and Moderna to transfer their technology to manufacturers around the globe. The Financial Times reported this week that South Korean vaccine makers are poised to expand but are struggling to secure intellectual property licensing deals with the two companies.

Biden is likely to make some kind of announcement about addressing the pandemic when the U.N. General Assembly convenes in New York for its annual meeting in September. The administration is considering creating a government-owned manufacturing plant that would be run by a private contractor — a plan endorsed by PrEP4All. But a person familiar with the proposal said it was only a possibility at this point.

There are challenges with such an approach, particularly if experienced vaccine makers do not participate, as the situation with Emergent BioSolutions demonstrated.

Krishnamoorthi said the Democrats’ plan was modeled on PEPFAR, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, an initiative started by President George W. Bush that has invested $85 billion to address the global AIDS epidemic.

Public Citizen, a nonprofit consumer advocacy organization, has a plan calling for the government to invest $25 billion in developing regional manufacturing hubs around the world, which it says would produce enough vaccine for low- and middle-income countries in a year.

“He’s said, ‘We’ll be an arsenal for the world’ — that’s a little vague,” said Peter Maybarduk, who directs Public Citizen’s Access to Medicines program. “What we see instead are dribs and drabs, like the excess of the U.S. supply, maybe if we’re not using it for third shots at home.”

May 01: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05