Last summer, the publishing house Bloomsbury USA drew substantial criticism for featuring a white girl with long, straight hair on the cover of Australian author Justine Larbalestier's "Liar," a young adult novel about a girl whom the author describes as "black with nappy hair which she wears natural and short." At the time, Larbalestier blogged not only about her own disappointment but about similar examples of cover whitewashing, and the pervasive belief among publishing professionals that "black books don't sell" -an assumption apparently based on the premise that a "black cover" is the primary characteristic distinguishing such books from better selling titles. "Yet I have found few examples of books with a person of colour on the cover that have had the full weight of a publishing house behind them," said Larbalestier (adding in a footnote, "And most of those were written by white people"). "Until that happens more often we can't know if it's true that white people won't buy books about people of colour. All we can say is that poorly publicised books with 'black covers' don't sell. The same is usually true of poorly publicised books with 'white covers.'"

Eventually, after the blog-driven uproar grew loud enough, Bloomsbury changed the cover to better reflect the protagonist's appearance. "I hope that the debate that's arisen because of this cover will widen to encompass the whole industry," Larbalestier wrote, continuing:

I hope it gets every publishing house thinking about how incredibly important representation is and that they are in a position to break down these assumptions. Publishing companies can make change. I really hope that the outrage the US cover of "Liar" has generated will go a long way to bringing an end to white washing covers. Maybe even to publishing and promoting more writers of color.

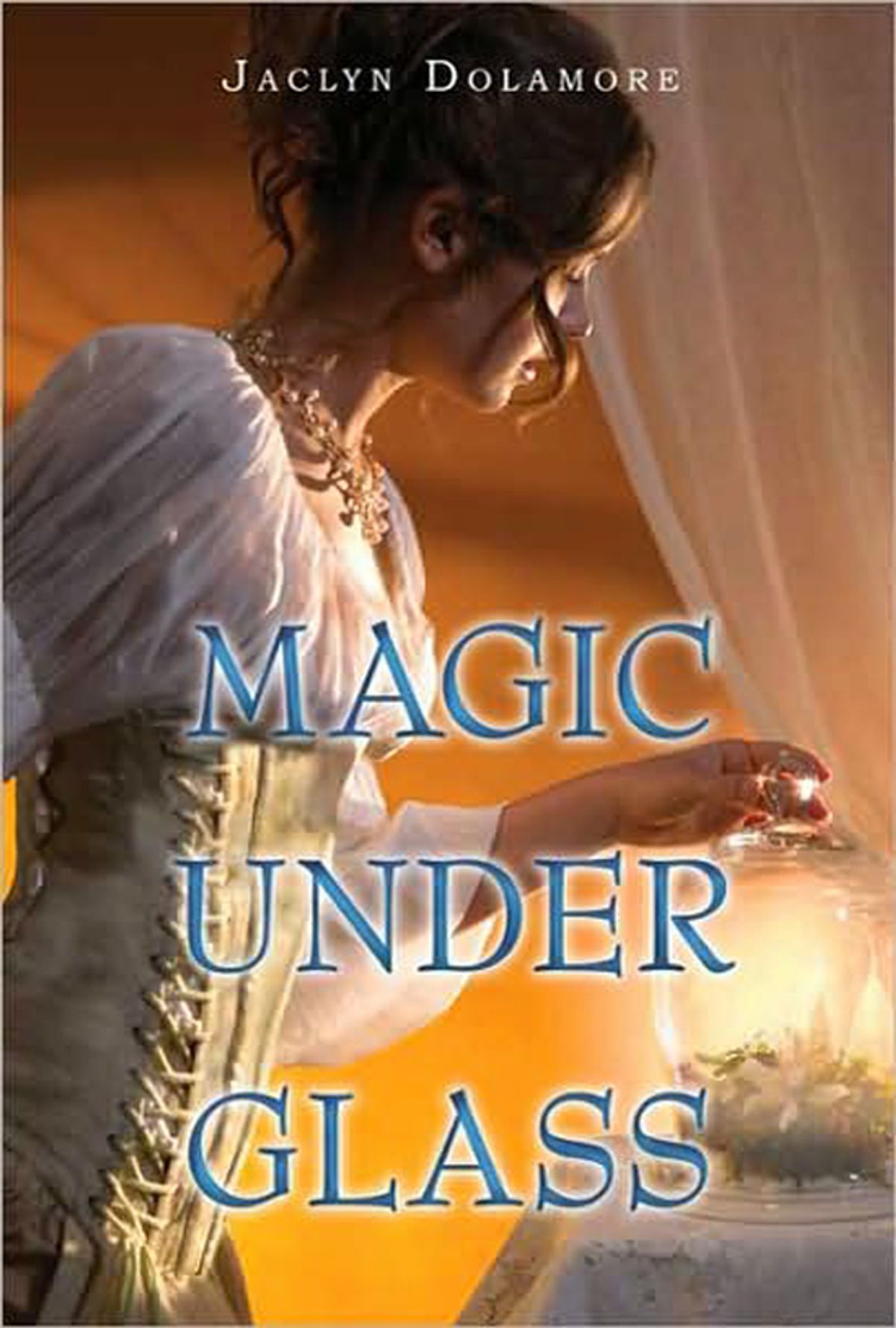

Apparently, though, the kerfuffle didn't even get Bloomsbury thinking too hard. The same publisher has done it again, releasing Jaclyn Dolamore's "Magic Under Glass" -- the protagonist of which is clearly described as having brown skin -- with a young white woman on the cover. Bloomsbury's fear of losing the white market was evidently greater than their embarrassment over the "Liar" debacle -- unless, of course, what they chiefly learned from the "Liar" debacle is that you don't need to put as much money into publicizing a novel if its packaging is sufficiently controversial (in which case, you're welcome, jerks).

I'd put my money on the former, though. Larbalestier's cover was the first to gain significant attention for whitewashing, but it wasn't the first, and thanks to the enduring strength of the simplistic "covers with people of color don't sell" belief, no one should be surprised it wasn't the last. In an article on race in children's publishing, Mitali Perkins quotes Ursula Le Guin, who said at BookExpo America in 2004, "Even when [my characters] aren't white in the text, they are white on the cover. I know, you don't have to tell me about sales! I have fought many cover departments on this issue, and mostly lost. But please consider that 'what sells' or 'doesn't sell' can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. If black kids, Hispanics, Indians both Eastern and Western, don't buy fantasy -- which they mostly don't -- could it be because they never see themselves on the cover?" (Three years later, the advance reading copies of Le Guin's "Powers" were "released with a white model on the cover despite the protagonist's Himalayan ancestry.")

Let's assume for the sake of argument that covers with people of color on them don't sell, and it's only because of the cover images -- not a lack of publicity and marketing support from the publishing house, the books being crappy, the authors being unknown, the booksellers shelving them incorrectly, the sad state of book sales in general, or all of the above. Even if this were a scientifically proven fact, there would still be good reasons for publishers to stop trying to fix the problem with white models. For starters, there's the plain dishonesty of it. That's apparently not a major concern, judging not only by the persistence of cover whitewashing but by the charming words of an anonymous publisher who told critic Jessica Mann that the decision to put a female corpse on the cover of a crime novel with a male victim was made because "Dead, brutalised women sell books, dead men don't." Since most readers never pay attention to who published any given book, the bait and switch probably has little effect on publishers' credibility, granted -- but you'd think they'd be more concerned with damaging the reputations of authors who supply the basic product. In Larbalestier's case, it was particularly problematic because her protagonist was, as the title suggests, a liar. Nevertheless, she writes, "I worked very hard to make sure that the fundamentals of who Micah is were believable: that she's a girl, that she's a teenager, that she's black, that she's USian. One of the most upsetting impacts of the cover is that it's led readers to question everything about Micah: If she doesn't look anything like the girl on the cover maybe nothing she says is true. At which point the entire book, and all my hard work, crumbles." Of course, authors are a dime a dozen, and those who don't sell -- even because of problems created by the publishing house -- can always be dropped. Still, actively sabotaging your own authors can't make very good business sense, can it?

And beyond that, I'm going to out myself as a Pollyanna and make the radical suggestion that maybe sales numbers aren't the only important factor to consider here. Yeah, I know, faceless corporations, profits, shareholders, blah blah blah. But the decision-makers here are still human beings -- and more important, so are the consumers. In addition to the high probability that publishers have created a self-fulfilling prophecy where covers featuring models of color are concerned, they are hurting people with their current practices. Blogger Ari of Reading in Color writes in an open letter to Bloomsbury:

I'm sure you can't imagine what it's like to wander through the teen section of a bookstore and only see one or two books with people of color on them. Do you know how much that hurts? Are we so worthless that the few books that do feature people of color don't have covers with people of color? It's upsetting, it makes me angry and it makes me sad. Can you imagine growing up as a little girl and wanting to be white because not only do you not see people who look like you on TV, you don't see them in your favorite books either.... Do you know how sad I feel when my middle school age sister tells me she would rather read a book about a white teen than a person of color because "we aren't as pretty or interesting." She doesn't know the few books that do exist out there about people of color because publishing houses like yourself don't put people of color on the covers. And my little brother doesn't even like to read, he wants to read about cool people who look like him, but he doesn't see those books in bookstores and now he rarely reads.

Putting a white person on the cover of a book about a brown-skinned character doesn't merely imply that people of color aren't worth as much to publishers; it pretty much says it outright. Because the only reason to do it is the assumption that a book won't hit its sales target unless white people buy it -- i.e., that white people are the market that really matters. When you look only at the numbers, that's probably true to some extent -- a higher percentage of white people means a bigger pool of potential consumers -- and it's true that white people often don't buy books by and/or about people of color. But I can make an educated guess that one other thing is also true: Books by and/or about white people fail in much larger numbers, if only because so many more of them are published in the first place. And that hasn't stopped publishers from signing up new white authors or putting white models on their book covers.

So really, publishers, if you're so convinced that a book with a dark-skinned heroine won't sell unless readers are tricked into thinking she's white, then just be honest about all of it -- admit that you don't want to risk publishing books about characters of color. Admit that white people are the only audience you really care about. Admit that you don't give a tiny rat's ass about that adolescent girl walking through a bookstore, trying to find a story about someone who looks like her and learning --probably for the umpteenth time that day -- that only white people can be pretty or interesting. But if you're not ready to admit all that, then you need to be putting people of color on covers where appropriate and supporting those books with real publicity and marketing budgets, so they stand a chance of not fulfilling your prophecy of doom.

Meanwhile, as consumers, we can put pressure on publishers to stop engaging in a deceptive, racist and hurtful practice, and explaining it away with a tired axiom that helps create the very problem it defines. Unfortunately, the most obvious protest, a boycott of these titles or Bloomsbury altogether, would hurt innocent authors and reinforce the impression that the market doesn't want books about people of color. But as Anna North at Jezebel suggests, there's no reason not to send a bunch of angry letters. Adds Ari at Reading in Color, "We should keep blogging, emailing, writing about this issue" -- Bloomsbury's been shamed into doing the right thing once before, at least. And as Larbalestier said back in July, perhaps the most important thing we can do -- especially white people, who could easily read nothing but books about ourselves, and far too often take that option -- is prove the prevailing wisdom wrong. "When was the last time you bought a book with a person of colour on the front cover or asked your library to order one for you?" she asks. If you want to see more of them, here's her best advice: "Go buy one right now. "

Shares