Billy was sporty, sociable and ambitious. He was 20, an RAF cadet, a fundraiser for various charities. Good grades. He'd never been in trouble with the law. Then a sudden onset of serious mental illness last June cast a dark shadow over Billy's prospects. Once contemplating a career in the military, he ended up on remand, with a period in jail.

"He thought people were going to our house to kill me," explains his mother Christine, recalling the attack. "It was so unlike him. It was scary because it was the first time I'd seen him like this."

Billy's mother describes how her son, almost overnight, started suffering from severe schizophrenic symptoms. He was constantly tormented by imaginary threats to his family, whispered by voices in his head. Previously sociable and physically active, he withdrew from his friends, broke up with his girlfriend and stopped exercising. He was admitted to a local NHS mental health unit, then told he was to be "treated in the community". Mental health workers, visiting Billy at home, were initially helpful. But the frequency of the visits tailed off. Billy, as many sufferers of severe mental health conditions do when not properly supervised, stopped taking his medication. Two weeks later, the hallucinations were louder than ever. Then he found himself on a busy north London high street, believing two men walking past were on their way to murder his mother.

Billy stabbed and seriously injured one of the men. The other defended himself and was unhurt. Billy was arrested. Billy's mother says the police immediately suspected the attack was unusual, and not just criminal behaviour. The first thing they said when they telephoned was: "Is your son OK? Is there anything we should know about him?"

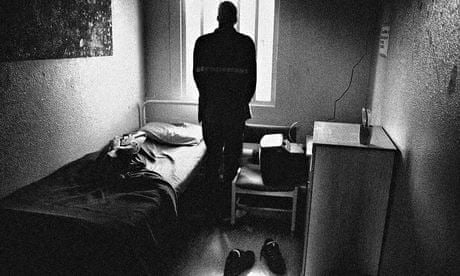

He was refused bail on the basis of his deteriotating health, and after a brief stay in Feltham young offenders institute (YOI), sent to maximum-security Belmarsh, a busy, loud and dangerous prison. Mental health provision is patchy and stretched. "I thought, 'This is the worst place for him to be,'" remembers Christine. "He's sick, he's scared, I don't know if he's taking his medication, I don't even know if the prison guards know about his condition."

Billy did not receive medical treatment, and his hallucinations grew more vivid and disturbing. His mother was stuck in a cruel catch-22. Only Billy could request a visit. But his rapidly deteriorating mental state had destabilised him to the point that he didn't even know he was in prison.

After four weeks, Christine managed to organise a visit. She found that Billy was on his own in a filthy cell. He had missed a critical heart check-up. No transfer to a psychiatric bed was in sight, despite a two-week recommendation for cases like his. She convinced him to start taking his medication, but could not get any more help for him.

According to Michael Spurr, chief operating officer for the National Offender Management Service, 10% of the prison population has "serious mental health problems" at any one time – currently about 8,000 prisoners. Twenty percent of prisoners have four of the five major mental health disorders (depression, bipolar disorder, ADHD, schizophrenia and autism). According to a 2006 article in the British Journal of Psychiatry, 25% of female prisoners and 16% of male prisoners were treated for a mental health issue in the year before custody. Despite thousands of prisoners needing mental health treatment, there are huge bed shortages. New figures from NHS England show just 600 high-security and 3,000 medium-security beds are available. Most patients will stay in mainstream prisons, where their medication regimes are unsupervised and over-stretched nursing units are their only hope of treatment. And for those unlucky enough to share a cell with someone who should be hospitalised, a jail term can turn into a death sentence.

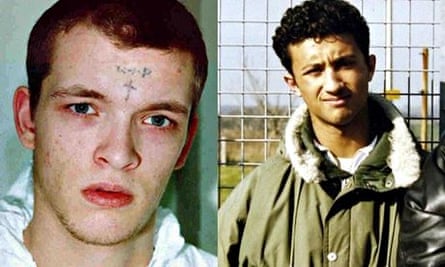

In September 2003, two men, Anthony Hesketh and Clement McNally had been "two-ed up" or assigned to share a prison cell in HMP Manchester, a "local" prison that receives prisoners from the courts and warehouses them until they are re-allocated. By any account, it was a mismatch: McNally, 34, was a petty criminal and convicted killer starting a life sentence, while Hesketh, 37, was serving four months for driving while disqualified. They would have spent upwards of 20 hours a day in each other's company. But there was a further difference: McNally was psychopathic and deeply paranoid; he believed himself to be "Satan's hands and eyes".

One night, Hesketh was sitting on his bed rolling a cigarette when McNally approached him from behind and, using a torn T-shirt, began to garrott him. Hesketh fell to the floor. McNally knelt on his back until he stopped breathing. A year later, McNally admitted manslaughter on the grounds of diminished responsibility and was given a second life term. He told investigators the killing was "exciting, better than sex", and that he would kill again if given the chance.

At the 2009 inquest into Hesketh's death, the jury heard that McNally had been diagnosed as having an "emotionally unstable personality disorder", with symptoms leading to outbursts of anger and violence. In the weeks before the killing, he had daubed the walls of their cell with satanic sayings, and frequently lost his temper. Prisoners told the jury that everyone was aware of how unstable he was becoming. All prisons are required to carry out a risk assessment before placing inmates in shared cells. In McNally's case, this had consisted of asking him, "Are you safe to share cells?"

This was not the first homicide by an inmate with mental health problems. In March 2000, 19-year-old Zahid Mubarek was battered to death by his cellmate at Feltham YOI. His killer, Robert Stewart, also 19, was found to have a deep-rooted personality disorder. Our investigation has found that, of 18 resolved prison homicides since then, half were committed by people suffering from a serious mental illness. In two cases, the murderers disembowelled their victims. Essentially, half of prison cell murders since 2000 could have been avoided if prisoners had not been forced to share cells with such unstable inmates.

Untreated mentally disturbed prisoners are also a danger to themselves. According to figures released by the Ministry of Justice in January, suicide rates in men's prisons in England and Wales have reached their highest levels in years. In 2013, there were 70 suicides, more than at any time since 2008. In women's prisons, the rate is dropping, largely due to safer custody measures recommended by Baroness Corston in a report published in 2007. The report was commissioned following a steep rise in the female prisoner suicide rate, including six deaths in a year at Styal prison in Cheshire in 2003. Self-harm levels in women's prisons, however, remain high. A Lancet report last year found that 20-24% of female prisoners self-harmed, 10 times the rate in men's prisons.

Some women slip through the new safety nets, too. In January, an inquest jury recorded a verdict of suicide for 24-year-old Amy Friar, found hanged at Downview prison, Surrey in 2011. The jury heard she had a history of mental ill-health, depression and self-harm. She was also a victim of rape and domestic violence. She had been identified as a suicide risk after an ex-girlfriend was found murdered, and she was placed under hourly monitoring. Later, that was reduced to nighttime only, despite an objection from a senior prison officer who thought she still posed a risk to herself. There were no observations in place on the day she killed herself.

The situation is not helped by the fact that mental disorders are often viewed by management as a discipline problem rather than a health issue. Woodhill prison in Buckinghamshire houses a Close Supervision Centre (CSC), one of three set up in 1998 to hold the most disruptive and violent prisoners – not, supposedly, those with mental health issues. But in a letter seen by the Guardian in 2012, the unit's manager noted that "the presence of a mental disorder or personality disorder is not uncommon within this population". In 2011, one prisoner in the unit sliced off both his ears in two separate incidents, and last October, another inmate cut off his ear. Prisoners there are subjected to "controlled unlocking", meaning four or five prison officers, in full riot gear, confront them when their cells are opened. Inmates at Woodhill CSC, past and present, told us mental health support is "virtually non-existent".

Most prisons employ mental-health teams, but numerous reports bear witness to the strain they are under, with a handful of specialists often responsible for the entire prison. In January a prisoner at Dovegate prison in Staffordshire claims that he asked to see a mental health nurse and was told by prison staff the only way to do so was to self-harm, so he did.

In 2007, Lord Keith Bradley was asked by the government to investigate a new policy of diverting people with mental health problems away from the criminal justice system. The Bradley review was published in April 2009 and, in principle, the government agreed to its recommendations. A critical point was "to facilitate the earliest possible diversion of offenders with mental disorders from the criminal justice system," through dedicated psychiatric staff at police stations. Last January, a national inspection report showed that little progress has been made on that front. Only one of the police forces that inspectors visited had such a mechanism in place. Most mentally ill prisoners are still sent to prison, not to hospital. There are slight signs that this might be changing. In January, the government announced a pilot scheme in which mental health specialists were employed at 10 police stations. But it could be years before any effective change to the system occurs.

But even if prisoners do reach secure units and are given treatment, problems then arise due to bed shortages. NHS England told us that around 3,000 beds were available to prisoners in the "low-security" category. Andy Bell, deputy chief executive of the Centre for Mental Health, however, dismisses this statistic: "These low-security beds are never used by the prison service." NHS England also told us about 600 "high-security" beds, but new figures from the same body reveal how these rarely become available. Just 24 prisoners were transferred from a prison to a high-security bed between April and December 2013. This leaves most prisoners waiting for a place on a "medium-secure" ward, of which there are 3,000.

"Many prisoners are assessed numerous times before they can be transferred to hospital," says Bell. "And the average length of stay in secure care is two years, because of a lack of intensive community support for people who no longer need detaining in hospital, and of care for those who need to be returned to prison after treatment." Which means that "the system is blocked," says Bell. "The waiting list is appallingly high."

Earlier this year, we spoke to a patient in a privately run, medium-secure mental health hospital. He had arrived there from prison after being sectioned. He had sought help from prison doctors after fearing he was becoming mentally unstable. According to "Matty", the regime at the hospital is becoming "more chaotic by the day". He says assaults are increasing and blames the increase in violence on an influx of patients who should be in high-secure units. Officials have told Matty that there is no room in the high-secure estate, with places reserved for "really dangerous people".

Nick Hardwick, chief inspector of prisons, asked about these figures, doesn't mince his words, and condemns the penal mental health provision as "a national disgrace". He refers to Highdown prison in Surrey, on the site of a former asylum, where more than 10% of the inmates require mental health support. "Many of those in the prison are not so different from the patients incarcerated in the old asylum." And Highdown isn't necessarily the worst off. In other prisons, Hardwick says, as many as half of inmates may need help.

Frances Crook, chief executive of the Howard League for Penal Reform, argues that the failure to invest in community mental health means people are being swept into prisons rather than treated properly. "We are recreating Bedlam," she says. "People who could be helped to lead happy, constructive and crime-free lives are condemned to a petty criminality and a life of incarcerated violence at taxpayers' expense."

Nevertheless, Norman Lamb, Liberal Democrat MP and minister of state for care and support, insists the situation is under control. "We are determined to make sure prisoners get the care they need, including acute beds. However, a diagnosis of mental illness doesn't necessarily mean a hospital bed is needed. When doctors decide a prisoner needs treatment in a secure psychiatric unit, they are moved out of prison as quickly as possible. But a one-size-fits-all target does not work, and doctors must decide what is best for their patients."

So what of Billy, stuck in Belmarsh prison? Did he make it into a secure bed? The Ministry of Justice won't comment on individual cases. But a Department of Health spokesperson told us that "any decision to approve a prisoner transfer to secure services is ultimately a clinical matter and this determines how quickly a transfer takes place". We then asked Phil Wragg, the governor of Belmarsh, why Billy was not being transferred. He cited security concerns.

Finally, after repeated calls to the Ministry of Justice and to Belmarsh, the objections to Billy's transfer were suddenly dropped. He was quickly transferred to a psychiatric unit and is now receiving appropriate care.

"He always wanted to plead guilty. He knew he'd done something wrong," says his relieved mother. "But he needs to be doing his time where he can get access to doctors and his medication."

Some names have been changed

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion