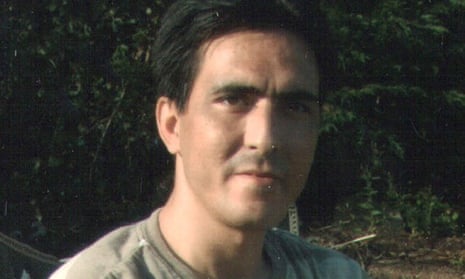

Bijan Ebrahimi was targeted by his neighbours, accused falsely of being a paedophile and, finally, beaten to death in July 2013 by Lee James, who is serving a prison sentence for murder. James bears the ultimate responsibility for his death.

Stephen Norley, another neighbour, was sentenced to four years for assisting an offender. However, the police officers who failed to recognise Bijan’s repeated cries for help, turned him away, and treated him with disbelief, rudeness and contempt, bear their share of responsibility too. So do Avon and Somerset police, which trained those police officers, and took far too long to apologise for its failings.

So, two years after a murder that Bijan’s family wonder, with justification, could have been avoided, what lessons can be learned from his terrible death? What can be built as a fitting memorial?

As one of the coordinators of the Disability Hate Crime Network, I wrote to Bijan’s family after his murder, and we agreed to request an appeal of the sentences to the attorney general, which was turned down. We felt that the crime against him was a hate crime – that the crime was motivated by both race and disability and the sentences against those convicted should be increased to reflect that fact.

False allegations of paedophilia, as I wrote in my book, Scapegoat: Why We Are Failing Disabled People,are all too commonly deployed against disabled men who are often then subjected to the violence of a lynch mob. In one year alone, I found five such killings linked to false sexual offence charges. There is a grim, but familiar pattern of disabled men falsely accused of sexual crimes they didn’t commit.

The first lesson, therefore, that must be learned from Bijan’s case and taken on board by every police officer in the UK, is that such an allegation is highly dangerous and should be “red flagged” as a possible indicator of a future hate crime. Secondly, cases where two possible indicators of hate that coincide (here, race and refugee status, as well as disability) should be “red flagged” too, since they clearly increase the risk to the victim as they can be attacked for two or more reasons. We cannot see into Lee James’s mind. He may have targeted Bijan for both factors. Investigating one factor is not good enough.

Far too little is known about the motivation of perpetrators of disability hate crime. I carried out a small survey earlier in the year, and reported on the results in the Guardian, but more research is urgently needed.

Thirdly, the emphasis on localism in policing means that learning from individual cases goes only so far. Avon and Somerset police will, of course, change after this catastrophic failure to protect Bijan. Leicestershire constabulary, similarly, changed after its failure to protect the Pilkington family from years of disability-related harassment culminating in Fiona killing herself and her disabled daughter after years of torment in 2007.

Many of the coordinators of the Disability Hate Crime Network, including myself, serve on national police advisory bodies on disability, but I feel that moving on from such terrible cases is hampered by policing structure. To what extent would a national police force, instead of 43 individual police forces in England and Wales, improve overall learning from catastrophic failures? There is good practice in several police forces, such as Lancashire and Sussex, but there is also poor practice, which has to end somehow.

One of the conversations I had with Bijan’s sister Manizhah was about a memorial to him – self-defence courses for disabled people. The thinking behind this is twofold: to give disabled people more self-confidence in social situations and to break down the barriers between disabled and non-disabled people by, in the future, providing more inclusive sports facilities. Funding, of course, is a barrier. Perhaps Avon and Somerset police could get involved in providing disabled people in the Bristol area with self-defence classes, alongside a disability group. What a fitting legacy to Bijan Ebrahimi that would be.