Scientists from the US Navy have now treated a patient they say may be the first ever to suffer from internet addiction by way of Google Glass. News articles on the research findings have headlines like “Google Glass user treated for internet addiction caused by the device”, “Google Glass User is First Patient Diagnosed with Internet Addiction Disorder” and “Guy Who Used Google Glass for 18 Hours a Day Got Addicted to Being a Glasshole”. I am waiting for the one called “Scientists Discover People Become Reliant on Technology: Well, Obviously, Says All of Humanity”.

The story here is that a Navy servicemember checked into military-run rehab for substance abuse, and as part of his treatment was required to give up electronic devices altogether. In the case of Google Glass, he resisted; he said he’d been using the device 18 hours a day, and that he became cranky without it. The patient would also frequently forget that he wasn’t wearing his Glass and involuntarily tap his temple to turn it on. Tics, irritability, cravings – voilà: you’ve got your first official Glasshead, and doctors warning that (as reported here in the Guardian) “people are clearly suffering from problems related to internet addiction, and it is only a matter of time before the research and treatments catch up”. Of course, the patient was also an addict of the more standard sort – an alcoholic going through withdrawal. But, no, it must be the fault of the internet, spookily worming its way into his brain!

Good people would not deny a patient’s suffering; it is, however, worth questioning the implied or overt angst about the menace of the modern world. It’s worth questioning the leap from “technology affects us” to “technology will ruin us”. This is routine by now; we are constantly forgetting and rediscovering the anxiety that video games or the internet or whatever are “rewiring our brains”. And they are! They are totally rewiring our brains! So are other modern scourges like television and cars and music and language. “Rewiring the brain” is actually just how learning works. And being reliant on technology, or physically integrating technology, or having your mind and life inscribed by technology – none of this is actually new.

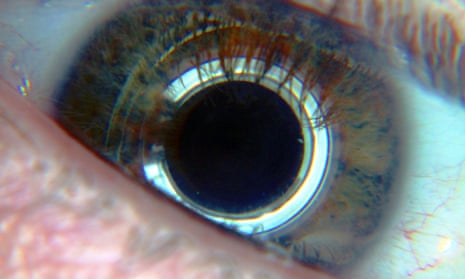

The US Navy patient said that Google Glass had started to creep into his dreams; his mental images looked as if they were viewed through the device’s window. But when I dream or call up mental pictures, I envision how they look through the thin pieces of plastic I wear in my eyes at all times. With a few very frustrating exceptions, I can see clearly in all my dreams, even though that’s far from my natural state; I’m so accustomed to my enhancement that even in dreams I can’t imagine going without it.

Should I be concerned that my contact lenses are infecting my subconscious?

Nobody’s likely to say I’m “addicted” to my contacts, even though I cannot function without them. Nor is anyone likely to call someone an addict for relying on a hearing aid or prosthetic limb or pacemaker, or a cane or glasses or mechanical spider eyes or those built-in, wrist-mounted flamethrowers everyone has nowadays. Integrating technology into your body – being a cyborg, in other words – is perfectly normal, and has been perfectly normal for centuries. (Picture an oldey-tymey pirate. Peg leg? Hook hand? CYBORG. And it goes back even further: the first glasses were invented in the 13th century, the first prosthetics date to BC).

So why do we go into panic mode when someone introduces a new way for humans to twine their lives with technology?

Part of it is just our relentless human drive toward mediocrity; anything new and confusing, however valuable, will be a source of fear and trumped-up nostalgia. But we also make a fetish of the “natural”, as though existing in a state of nature – somehow rooting technology out of our bodies and our lives – would work out especially well for human beings. Don’t kid yourself; in a state of nature, you’re a grub. If it were truly troubling for our dreams to be altered by our technological enhancements, we wouldn’t be able to dream any bigger than “standing naked in a cave, supposed to star in the school play, unable to remember any lines, but totally unaware of it because nobody ever invented drama or school or writing or language”. And if you were me, it would be blurry.

I grew up on Greek mythology, and sometimes I think about the story of the Titans Prometheus and Epimetheus. You probably remember that Prometheus, creator of mankind, ended up chained to a rock having his internal organs nibbled by birds, a punishment for stealing fire from the gods. His brother Epimetheus had created the animals, and sneakily given them all the good bits with no skills left over for humans. (This is how my D’Aulaire’s Book of Greek Myths tells it, anyway, and the D’Aulaires are pretty much the David Attenborough of my early childhood reading; I do not have it in me to doubt them). Prometheus stole the fire to keep his clawless, toothless, dull-sensed, soft-skinned huddling masses warm.

This is a myth, of course, but like many myths it gets at something vital: on a base level, we suck out loud. The only thing that allowed our species to survive, become great, and then become terrible again was technology. Fire, yes, but then language, houses, agriculture, books: technology is the pelts and claws and teeth we never had. Sometimes it literally gives us keener sight or hearing than we were born with, or replaces physical parts that no longer work; we integrate it into our bodies and make ourselves cyborgs. Other times, it makes it easier for us to create, access, trade and use knowledge. In a way, we integrate that knowledge into our bodies as well, because it rewires our brains – those mercifully rewireable brains that go a long way towards making up for other animals getting the shells and the wings.

Of course, for every Titan who brings newfangled fire to the grateful grubs, there will be some people who want to chain her to a rock and let the eagles eat her liver. But it’ll take more than sneers to curb our cyborg nature, because integrated technology is not newfangled at all; it’s practically as old-fangled as it gets. We’ve been posthuman almost as long as we’ve been human, and that’s an essential component of the human experience. We’re not losing ourselves to technology; technology makes us who we are.