How Book Publishing Has Changed Since 1984

A look back at an age of old retail and indie bookstores, before computers, celebrity memoirs, and megachains came to dominate the literary world

In April 1984, I arrived at Random House as a senior editor after nearly two decades at the Washington Post. Publishing is now undergoing the most significant transformation in the way books are distributed and read since development of high-speed printing presses and transcontinental rail and highway systems. Looking back at the industry in the 1980s may help to explain how much has changed and what has not.

On my first day at Random House, I encountered the fundamental difference between the news business and the book business. In newsrooms, you got the story, it was printed in the paper, and then you went home. In publishing, you acquired the story, got it written, had it printed, and then—crucially—figured out how it should be sold. Because books have no advertising or subscriptions to provide revenue, the combined mission of obtaining the story and selling it was and is the essence of the art of publishing. For all that today's technology and marketing methods have evolved, the basic task remains the same: to define and find the audience for which the book was written.

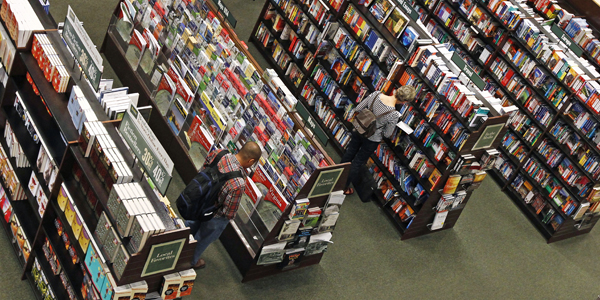

To help me recollect the retail scene of the 1980s, I called Carl Lennertz, who was then a young Random House sales representative and now coordinates HarperCollins's relationships with independent booksellers. I remembered Carl as especially wise about how books were sold, and he was generous in educating me, who despite my fancy title and extensive background in news-gathering was very much an ingénue when it came to publishing. So with Carl's help, here is where books were sold in 1984: The biggest names in retailing were Walden, Dalton, and Crown, still relatively new as national chains. They made books available in malls as populations moved to the suburbs. Led by Crown, which was mainly in the Washington, D.C. area, the chains adopted discounting as a strategy and limited their selections to put greater emphasis on bestsellers and "category" books such as self-help, diet, and romance. Barnes & Noble and Borders, which became dominant in the 1990s with superstores (absorbing Dalton and Walden, respectively; Crown went out of business), were still in their early stages. The rise of the chains had the greatest impact on department stores such as Macy's and Marshall Fields, which in their heyday were centers of bookselling alongside housewares and clothing. By 1984, that era was ending.

Independent bookstores—according to Carl's estimate, there were about 3,500 full-service booksellers, which is twice the number there are today—played a major role, since they had the ability, when enthusiastic, to turn first novels into bestsellers. Some of today's leading independents, such as Tattered Cover in Denver and Powell's in Portland, were already influential. But many other stores of that era closed, overwhelmed by the chains and superstores, and eventually Amazon and the rise of online retailing. "Hand-selling," as it is known, is still the independents' specialty, and while their role is smaller than it was, they remain at the spiritual core of publishing. It is encouraging to see so many of them holding their own and adapting to the digital age in various ways. In the past three years, several hundred new stores have opened, often where there were none before. At their best, the "indies" anchor communities with author signings, reading groups and other events.

The Book-of-the-Month Club and The Literary Guild were still very prominent in the 1980s, with millions of members. Their monthly choices were eagerly awaited by publishers. But, like the department stores, the "clubs" gradually lost their place as bookselling moved into so many new venues, and their remnants focus on niche markets with much smaller constituencies.

The biggest change in publishing, as with society in general, came with the arrival of computers. In 1984, orders were still delivered by phone, fax, and mail. At Random House, I received the daily sales numbers on a mimeographed sheet, transcribed from some master ledger. Reprints of books took four to six weeks to complete, and tracking sales and returns were, by today's record-keeping standards, astonishingly slow and inefficient.

Mass-market paperbacks sold in drugstores and newsstands, which were expanding into malls also and were a very substantial business. One of the major developments at Random House in 1984 was the August publication as a trade paperback "original" of Jay McInerney's Bright Lights, Big City, an innovative novel that skipped the hardcover stage, captured the mood of Generation-X readers, and sold, over time, untold (I'm guessing millions) of copies. From then on, these originals, also known as "quality" paperbacks, to distinguish them in price and style from the drugstore variety, were "cool," and their aura expanded the market for trade paperbacks beyond the classic reprints that were their staple adding an important new category for readers at just the right time.

The size of advances—the upfront guarantees that authors receive—were just beginning to fascinate the media, as agents increasingly took books to auction, pitting publishers against each other and driving up the numbers. At Random House, however, the biggest-selling authors were the incomparable Dr. Seuss as well as James Michener, whose regular blockbusters of historical fiction were huge bestsellers. Neither author took advances. Their revenues were so large and steady that they had a permanent drawing account and relied on the publisher and their financial advisers to see that the money was properly invested. For me, as a nonfiction editor, the big change came in the summer of 1984, when Geraldine Ferraro was selected as the Democratic candidate for vice president. The likelihood she would write a book about her experiences was obvious. "Let's go to $50,000," a senior Random House executive authorized me. After the election, Ferraro's book went to auction and sold for more than $1 million. A year later, I was the high bidder for House Speaker Tip O'Neill's memoirs, also for about $1 million, which was still a big enough deal to merit mention on the front page of the New York Times. Fortunately, O'Neill's Man of the House was enormously successful. The bull market for memoirs by politicians and celebrities had taken off, and to this day seems to grow, with top-of-the-line advances worth many millions. (Bill and Hillary Clinton received, reportedly, a combined $20 million.)

One of Random House's big books that spring was the diary of New York's governor, Mario Cuomo. Whatever else Cuomo wanted for his book, outselling New York's Mayor Ed Koch's number-one bestseller was a key goal. That never happened. When Cuomo delivered the finest speech of his career at the San Francisco Democratic Convention, he flew back overnight and called Jason Epstein, Random House's legendary editorial director to complain that his wife Matilda could not find copies of his book in stores around the Cow Palace, where the convention was held. Jason listened to Cuomo's lament and quietly observed: "Governor, no author since Homer has ever found his own book in a bookstore."

Whatever else has changed in publishing over the years, that wry insight still resonates, except that you can now look yourself up on Amazon and elsewhere on line for reassurance that your book is actually for sale, which is progress.

Coming next: "Good Reviews Are No Longer Enough."

Image: Reuters/Kevin Lamarque