Passengers have found a variety of reasons to object to the Transportation Safety Administration's new screening policies, a combination of advanced-imaging technology scans and pat-down searches, which went into effect Oct. 29. Some see the full-body scans as a radiation risk. Some say the measures violate civil liberties, And for some, like John Tyner, a San Diego software engineer, the new screening measures represented something more immediately terrifying: the specter of sexual menace. Tyner is being investigated for an $11,000 fine after he walked away from a screening he considered "sexual assault."

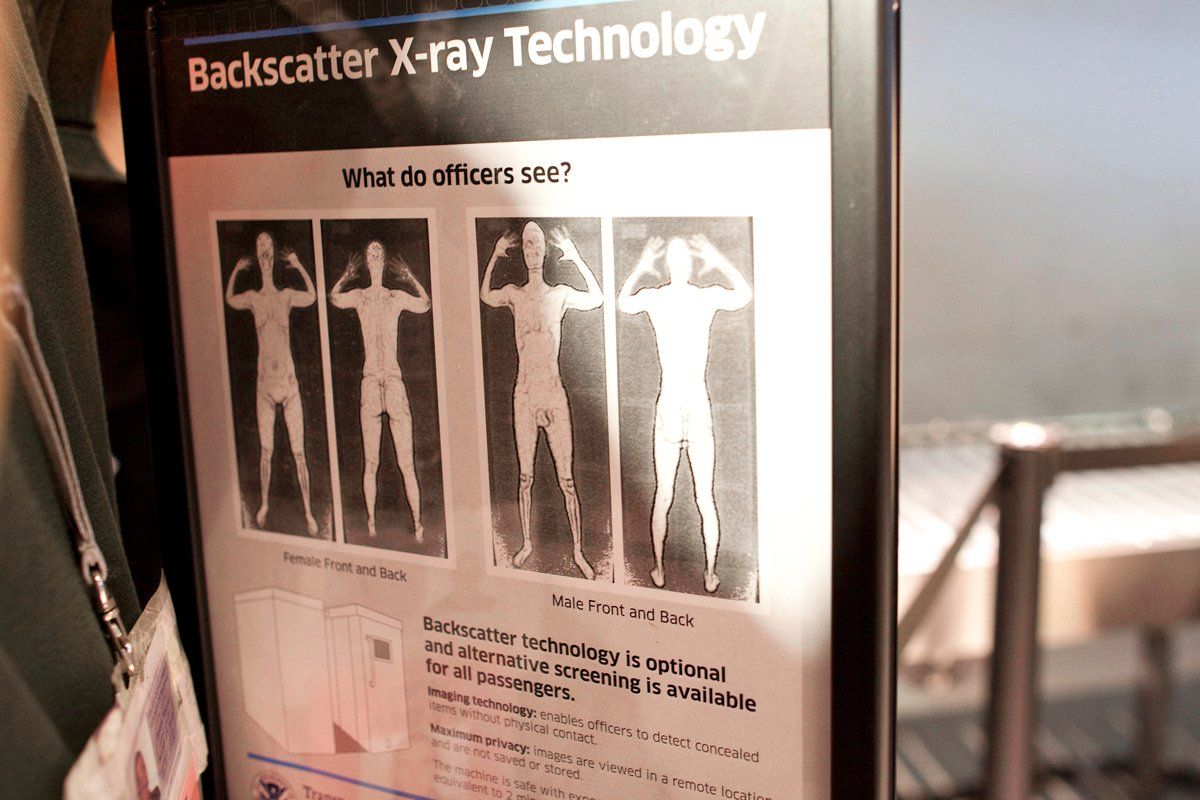

The TSA, on the other hand, argues that these screenings are not only safe, they're necessary. In an era of plastics-based explosives, metal detectors aren't sufficient, says Nick Kimball, a spokesperson for the TSA, and the new body scanners are the best available option. The body scan creates a digital snapshot of passengers underneath their clothing, allowing screeners to see any hidden contraband. Passengers who decline the scan are subject to a pat-down to achieve that same goal. It's a pat-down that many travelers say may be more thorough, but is also more invasive and humiliating than previous security frisks. "It was a horrifying experience. I was touched in my private parts, in my genital area, without consent and without warning," says Erin Chase, an Ohio woman who flies several times a month. (TSA says that all airline officials should tell passengers what's going to happen prior to a pat-down.)

For women and men who have already been sexually assaulted, the new screening rules—or just the threat of these rules—present a very real danger. They can be triggering events, setting off a posttraumatic-stress reaction. "I started crying. It was so intimate, so horrible. I feel like I was being raped," an anonymous rape survivor recounted on a Minnesota blog. Melissa Gibbs, a spokeswoman for We Won't Fly, a group protesting the new regulations, says that a rape survivor she spoke to had a panic attack as an agent began touching her leg.

"After a sexual assault, it seems that many survivors have difficulty having their bodies touched by other people," says Shannon Lambert, founder of the Pandora Project, a nonprofit organization that provides support and information to survivors of rape and sexual abuse. This fear of contact even extends to partners and, often, medical professionals. "A lot of survivors do not want to be in positions where they're vulnerable. They put up defenses so that they can be in control of their body. In cases like this, it seems like some of that control is going away."

If that sense of control is violated, it can lead to more than hurt feelings. There's a physical reaction associated with a triggering incident, and the response can vary from person to person. "It could lead to a person shutting down and becoming noncommunicative, it could result in a person becoming emotionally upset, it could trigger flashbacks, not just the thoughts and feelings they experienced, but perhaps other sensory experiences," says Jennifer Marsh, director of the National Sexual Assault Hotline for the Rape Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN).

Defenders of the pat-downs argue that they're not all that different from what was used before (though frequent fliers such as Chase would disagree). How and when they're executed has also changed. Previously, pat-downs were reserved for those who failed a metal detector or who were randomly selected for a search. But now, a pat-down is used both when passengers opt out of the scan and when scanner technicians can't capture a good image. With 385 scanners in use in 68 airports, some abuse survivors worry that the chance of incurring a pat-down has now increased. And that threat of being retraumatized is enough to keep some of those people from flying. "There's no way that I would go through that as a survivor," says blogger Melissa McEwan. Her posts on the invasive pat-downs have generated numerous comments from other survivors who have either experienced panic attacks as a result of the new screening process or are avoiding flying so that adverse reactions won't be triggered. Gibbs, herself a survivor, is planning a national boycott of the airline industry, along with We Won't Fly, on Nov. 23.

The pat-down itself is not the only thing that could cause a reaction, say counselors who work with people who have experienced sexual assault. "We've had a number of survivors who have had their pictures taken and put online," as part of a sexual assault, says Lambert. "So for them, even though [the TSA photo is] deleted, even if the person is in the other room, the idea that the photo's being taken can be difficult to handle." Lambert also notes that for adults who were assaulted as children, watching their children go through either invasive photographs or excessive pat-downs can be traumatic as well. (Kimball says that the machines automatically delete photos before moving on to the next passenger, and that the screeners, who work in a separate room, never see the passenger, while the agents working with the passenger never see the pictures.)

Both Lambert and Marsh says that through better communication and training with TSA agents, as well as relaxation exercises and therapy survivors' reactions to the pat-downs can be mitigated. Still, the pressure of airport travel can make the trauma of the search even worse. "This kind of situation has the potential to be really psychologically retraumatizing. Everything's happening so fast, there's a lot of pressure, a lot of people expecting you to, don't take too long, don't demand special privileges, don't ask questions. You have to catch your plane," says therapist Wendy Maltz, author of The Sexual Healing Journey: A Guide for Survivors of Sexual Abuse. "You don't have the opportunity to employ techniques that could enhance a sense of calm."

Passengers have the right to have an agent of the same gender perform the pat-down, but McEwan notes that any kind of unwanted touching can trigger an event. Moreover, men who are sexually assaulted are often the victims of other men—"but saying, 'Hey, I want a woman to do this' could lead to a whole other set of problems," Maltz says. Survivors and women's advocates also worry about the potential for bad actors, poor communication (as in Chase's case), and abuse of power will make an already bad procedure worse.

While the ACLU and some politicians are working to challenge the new policy, the TSA maintains that fears and speculation surrounding these changes are much worse than the reality.

"Our officers are trained to work with individual travelers with families to ensure a respectful screening process for everyone while providing the best possible security for all travelers," says Kimball, who notes that the procedures were determined by considering the overall safety of the passenger, and based on the best intelligence.

That's cold comfort for many men and women, who, thanks to the new security regulations, are feeling much less safe than before.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.