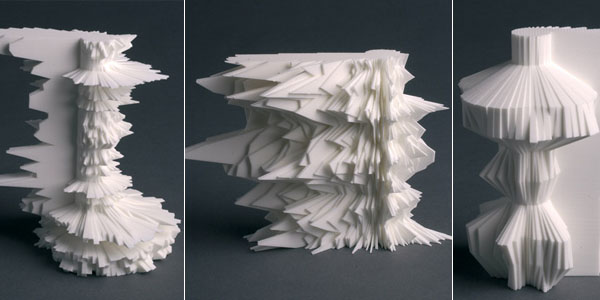

[Cylinder [extraversion.co.uk] is a small collection of physical data sculptures based on STL file data captured by the analysis of sound samples from spaces, creating site specific sculptures reflecting the acoustic of an environment. A mapping of the frequency and time domains produced cylindrical forms that represent the specific spatial characteristics of the sound input. Physical versions of the digital 3D models were then "printed" in 3D using stereolithography.

“Beginning with the primordial sounds of nature, we have experienced an ever-increasing complexity of our sonic surroundings. As civilization develops, new noises rise up around us; from the creaking wheel, the clang of the blacksmith’s hammer, and the distant chugging of steam trains to the ‘sound imperialism’ of airports, city streets, and factories.” - R.M. Schafer

Sound is an element that can define space, either by design in an effort to control and defend against noise (unwanted sound), or by using the composition of sound (often referred to as music) as an organizational method. This growing concern of the ever increasing complexities of our sonic environments is asking for innovative solutions to not simply mask or blind us to unwanted sound, but to compose it.

How can we integrate sound and site in a deeper and more meaningful way other then the traditional roles of sound integration with landscape architecture as simply a defense against sound, or imposing a non-site-specific musical composition to define spaces?

There is a needed opportunity of a hybrid landscape architect/sound artist, masterful in composing the inherent sonic qualities of a site and its context to create a unique spatial composition that more justly informs us about our environment. By recording and studying the existing site sound, and by using sound technology (accelerometers/sound sensors, microphones, speakers, etc.) a translation of that sound can be made to create a Composed Sound Filter, or an Acoustic Ecology Site Score which guides the spatial design.

We typically do not think of sound as having spatial implications. We have so naturally become tied to the visual it is hard to imagine this unseen force and how it can define and engage in our physical and spatial world.

Sound is often invisible to the eye, but, with the right tools, can be measured with a clearly defined form (amplitude), which has limitless possibilities of alteration as we begin to modify frequency and pitch. A powerful thought about sound and its relation to a landscape, is that it needs time to exist. Relatively speaking in comparison to architecture, landscape shares this same quality as it exists in the constantly changing moments of the environmental elements.

The amplitude and tone of sound has the ability to define space at various scales. The church bells found in the landscape of 19th century rural France for example prescribed an auditory region, and their meticulously composed tone and sonic reach actually defined the spatial regions of given townships. Disputes were common when these tones overlapped in the extents of neighboring towns, and also over who would ring the bell, and for what purpose.

These church bells at the time, served as spatial beacons for those lost in the nearby forest, and before lighthouses, as a sonic guide for wayward sailors. It was believed by many, that these bells had the ability to alter the weather, separating the clouds to create a clear path for angels traveling from heaven to earth.

Is there a modern example of the French church bell? Radio waves and stations perhaps act as a form of spatial definition, but I would argue that acoustically, our cities are two engulfed with an ever increasing amount of noise pollution that it becomes more difficult to spatially locate sound, which can have psychological implications to urban inhabitants.

The use of headphones can be viewed as of a kind of “urban tactic” in which we have the ability to deconstruct and construct the territorial structure of the city, to lose oneself in your own sonic universe when at any moment the physical world can interact and disrupt and bring the individual back to their surroundings.

As Harold Garfinkel in ‘Breaching Experiment’ (1967) noted. Making observable what usually goes unnoticed, the walking listener provides partial access to the mystery of appearance. By establishing a disjunction between the visible and the audible, a disturbance of the sensorium and form of strangeness in everyday life, it questions the evidence of the ‘perceptive faith.'

Our cities are rapidly growing and with it so does the production of noise pollution. Experts are greatly concerned about the possibility of universal deafness as the ultimate consequence as our cities produce untethered sound.

There is prominent research done, and being done in the recording of sonic environments that landscape architects can begin to pull from, in both built and non-built environments.

What if our landscapes could speak to us? How would our environmental relationships and connections change if our impacts received a verbal response? Perhaps we could finally answer the age old "If a tree falls in the woods" question.

[Recording the acoustic ecology]

On the ecological side. Scientists are intensifying studies to monitor ecosystems by recording and measuring biodiversity in soundscapes. Sounds of individual species have been the traditional area of focus, but as Michigan State University Ecologist Stuart Gage states:

"I'm not particularly interested in species. I'm interested in the biodiversity, species timing, habitat disturbances and communications issues. It's using sound as a metric to look at ecosystem dynamics."

Like the coal miner's canary, by audibly monitoring the landscape it might provide us insight into forthcoming ecological demise. But to hear and comprehend the warnings takes time, technology, and expertise. I wonder if our ancestors and those less effected by swelling urbanism were more in tune and thus able to detect ecological shifts purely by sound. How about the health of cities? If scientists were to study acoustical patterns of street noise could an early detection be made of overpopulation and mass transit deficiencies?

There was a time we all had the inherent capability to listen and speak with nature, but at some point something was lost in translation and we simply stopped listening.

The World Soundscape Project (WSP) was established as an educational and research group by R. Murray Schafer in the 1970’s as a response to the heightened concern of noise. It grew out of Schafer's initial attempt to draw attention to the sonic environment through a course in noise pollution, as well as from his personal distaste for the more raucous aspects of Vancouver's rapidly changing soundscape. Schafer was one of the first to inquire as to the relationship between man and the sounds of his environment and what happens when those sounds change.

The Brooklyn Bridge Park project completed in 2005 by Michael Van Valkenburgh and Associates is an example of a direct physical design response to abatement and construction to defend against unwanted sound. The site, located adjacent to the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway is deafening. According to MVVA’s research without any sound attenuating structures, the majority of the site would experience at least 70 decibels of noise generated by the BQE and Manhattan Bridge subway lines. At that noise level, two people standing six feet away from each other would need to shout to be understood (Berrizbeitia 241). MVVA recorded and mapped decibel levels at the site and addressed the incoming sound from the BQE by designing large planted landforms that physically block unwanted sound into the park.

[Landforms at the Brooklyn Bridge Park by MVVA defend against the massive sound of the BQE. Image by MVVA.]

Lawrence Halprin’s Freeway Park built in 1976 in Seattle addresses unwanted sound by cancelling out its affect with designed sound. Freeway Park, situated in the heart of Seattle city centre, was designed in the early seventies to reduce the impact of the the I-5 freeway and to reconnect the city centre with First Hill, an older area on the east side of the freeway. Halprin wanted to integrate the I-5 freeway into the park and to emphasize the highly urban nature of the site. The passing cars below make a constant, obtrusive element of the park. The 1976 park brochure describes the canyon fountain: “The freeway has been silenced, bested on its own terms, its power and scale matched and opposed by the natural force of churning water.” Halprin uses a sound with positive, natural environment connotations to negate what we view as unwanted sound, that of the active freeway.

[Halprin's Freeway Park. Waterfall couteracts freeway sound.]

In these two examples the understanding of the affect of sound on the site is studied but I think intentionally shallow. Both designers understood that the noise attached to the site had negative human impacts and chose to remove the noise through design intervention. In MVVA’s case, large mounds at Brooklyn Bridge were formed creating an acoustical opaque barrier from the sound source. With Halprin and Freeway Park, the idea that the more pleasurable sounds of water will overcome urban noise. Both projects, while successful in the defense against noise pollution begin to form a narrative of our understanding of the position we find ourselves in regard to it. A larger scale problem of uncontrollable noise coming from our built environments is treated through design that act as sonic blinders and band-aides.

I believe simple defense against noise pollution will be instrumental in future landscape architecture projects. However certain projects may lend to an opportunity and challenge to designers to rethink sonic site conditions and their treatment just as they would physical ones. Brownfield sites for example often speak to a greater environmental concern and the design engagement works in remediation to polluted site conditions to restore a landscape in a beautiful way, often with natural ecologic systems.

Another interesting project that the design was guided by a musical composition is the Toronto Music Garden, a collaboration between famed cellist Yo Yo Ma and Landscape Designer Julie Moir Messervy. Each dance movement within Bach's Suite No. 1 in G Major for unaccompanied cello, BWV 1007 corresponds to a landscape reflection in a different section of the Toronto Music Garden. For example, the Prelude becomes an undulating river scape with curves and bends. The first movement of the suite imparts the feeling of a flowing river through which the visitor can stroll. Granite boulders from the southern edge of the Canadian Shield are placed to represent a stream bed with low-growing plants softening its banks. The whole is overtopped by an alley of native Hackberry trees (Celtis occidentalis), whose straight trunks and regular spacing suggest measures of music.

The notion of using a music, the movement of composed sound to translate its physical qualities to spatial form is very exciting. But the issue I take with the Toronto Music Project is its lack of site specificity. What if we were to take this same idea but use the sounds that are being blocked, for example the BQE in the Brooklyn Bridge Park project, and reinterpret and compose those sounds to either create a harmonic sound installation for the park, or use this new composition to create an score, which guides the sequence of spaces and form for the design of the park?

By studying with greater intensity negative sound sources and understanding or working with sound/music composers/engineers we can not only design our physical environments, but sonically as well that build a narrative of multi-sensory experiences.

I did not come across a landscape architectural intervention that exemplifies my proposal, but there are several sound artists that are addressing the site specificity of sound spatially.

Ed Osborn, a sound artist and professor at Brown University does so with his Ground Creeper Variations project at the Fulton Mall in Fresno California. The project is a series of site-specific sound compositions designed for the space of the Fulton Mall, a downtown pedestrian area which was designed by Garrett Eckbo, who based the ground patterning and spatial organization from the pre-existing topography lines. The compositions are based on the physical space of the walkway itself using the location of various elements such as fountains and planters, sculptures, loudspeakers, and the curving patterns embedded in the pavement as sources for the pieces' compositional framework. Working from scans of the original plans of the Fulton Mall (which was completed in 1964), features of the walkway are selected and their images rendered into audio such that pitch, timbre, and textures of the sounds are determined by their placement, spacing, and contours.

Ground Creeper Variations is a good example of sound creation that creates an aural identity based on the physical makeup of a specific site. In sound artist Bill Fontana’s Harmonic Bridge, the sound sculpture explores the musicality of sounds hidden within the structure of the London Millennium Foot Bridge. This bridge is alive with vibrations caused by the bridge’s responses to the collective energy of footsteps, load and wind. This sonic world is inaudible to the ear when walking over this bridge (Resoundings). But the sound is then revealed by the use of the accelerometers (vibration sensors) that are listening to the inner dynamic motions of the bridge. Harmonic Bridge is realized by installing a network of live accelerometers on different parts of the Bridge in order to acoustically map in real time its hidden musical life. The live sonic mapping is translated into an acoustic sculpture by carefully rendering sounds from this listening network into a spatial matrix of loudspeakers. This sculpture will not only render the natural acoustic movements of the bridge, but will tune the presence of this live sonic data to the characteristics and architecture of the two spaces in which the work is presented: the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern, and the Main Concourse of Southwark Station of the London Underground.

Taking ideas from all the projects mentioned, which have their own merits in addressing sound. I believe it possible to create a new style and facet of landscape architecture that embraces the sonic environment as it would any other element that we typically deal with in designing a site. There is the inevitable existing condition of a site like the Brooklyn Bridge Park that experiences noise levels that are not suited for the human ear, and would disrupt any positive qualities of a space. As an alternative, MVVA might of built their sound barrier mounds, needed to disrupt the impossible decibel level of the BQE, but also installed within the mounds accelerometers which which pick up the vibrations of the massive sonic vibrations from the freeway. Mixed through multichannel speakers placed throughout the mound area a harmonic reinterpretation of the freeway noise resonates throughout the area. This would allow visitors to enjoy the site while still communicated the larger issues of overpopulation, our car-centric societies, and their impact on noise pollution in the acoustic ecology. The anticipated sound of the new design might also play a role in the sonic composition. The footsteps of joggers, children playing, etc. all could become the final “notes” that solidify the piece.

Another sound sensitive approach to designing the Brooklyn Bridge Park could be record the sound of BQE and other existing sonic qualities of the site, and working with a sound artist such Alva Noto, who often uses recorded urban sounds to compose music that suggests spatial implications, or soundscapes. Using a similar approach which Julie Moir Messervy did in creating the Toronto Sound Garden, an acoustic ecology site score would be developed from Noto’s composed piece based on the site recordings. The landscape architects would then use this score to development the site plan, manifesting the aural identity into a unique spatial identity.

I am sensitive to the fact that the aesthetics of sound are far different then that of visual sensory. Sound has a way of drilling in your head, and if unwanted, not as easy to escape as simply turning the other way, it surrounds us. So designing with this medium is extremely difficult, and perhaps why it has been avoided by landscape architects until now. My proposition of composing site specific sound to formulate spatial design would most likely be addressed for projects with a unique sound or noise quality. I also believe its possible, unlike the two examples of the Ground Creeper Variations and Harmonic Bridge projects, to work acoustically withing traditional medium of landscape architecture. Trees, combined with wind have the capabilities. Concrete, steel, and wood all have very different ways of absorbing and resonating sound and hold unlimited potential to be used to organised in such a way as to beautifully manipulate and harmonize with a given site soundscape.

This idea of sound’s ability to surround and consume us, especially in the urban realm is why it is so terribly fascinating, and necessary for landscape architects, as spatial designers, to begin using that quality to not only better inform design, but the ever increasing complexities of our sonic environments.