A man unearthed a carrot in the UK that looks like Buzz Lightyear from Toy Story. Scientists have come up with a material that is blacker than any black we know. Lloyd's of London insured an American football player's hair for the first time.

The new owners of Cadbury are searching for hi-tech wrapping to minimise melting. A health minister in the UK said that those suffering from obesity should be told that they are fat, not obese. The Spanish masterpiece Don Quixote de le Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes will be launched on YouTube.

Gasp.

I picked these random threads of information recently, plus, something about the best way - mathematically - to pour your second cup of coffee. Plus headlines on current affairs. Plus text reminders on retail sales and banking offers. Plus three flyers advertising a DJ night, a new restaurant and relaunched pest control services. Plus a surfeit of useless emails.

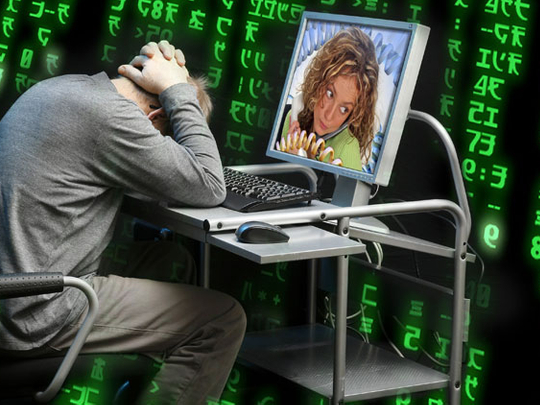

Result? My mind is gasping for control in this jumble of data and ideas. I don't know how to weave these threads into a tractable fabric of coherence. I don't know which ones are cohesive enough to act upon and which ones should be snipped. Ugh. It is annoying. So I ignored the report on the American football player's hair; yawned away the triteness of obesity; and binned those flyers.

Yet the jumble has left me nonplussed. But umm… wait. A few threads did get me thinking. I might look up Don Quixote on YouTube. I would really like to know whether I would be able to leave a chocolate bar in my parked car. The rest though?Ugh again.

Far from resembling an entire fabric of coherence, not a single thread of information made for a clear or an untangled idea. (Futile task that one.) I didn't know why scientists want a blacker black. Neither did I bother to find out why the talk on obesity is being structured in semantics instead of science. Frankly, I didn't have the time or capacity.

Soon I will spool in more threads of information. Only to find a bigger jumble where the sense-making measures of quantity and quality will get tangled further with information mediums. Ugh, the mediums. There are emails, chats, texts, posts, tweets…

The Economist's blog came up with a fabulous term for my mental state - magpie mind. It is easy to see why. The analogy - of the bird's habit to hop from one shiny object to another and my propensity to move from one tangential information titbit to another makes sense. And like the magpie, I don't focus long enough to look at what I pick up.

Forget the magpie mind parallel. (See what I mean?) There is a far better inclusive term to describe both my state of mind and my inability to handle this jumble of dataand ideas. It is called information overload.

Luckily, I'm not the only one suffering it.

Information: can we define it?

Information overload, the term and the phenomenon, is self-explanatory. At its crux lies the truth: there is too much information and not enough time to process it. And the principle: information is not the same as knowledge. So insidious is the rate at which this phenomenon is spreading that one could easily call it a modern-day malaise.

At least I do.

However, Dave Crenshaw, president of the National Association of Productivity Coaches and owner of Invaluable Inc, thinks information overload has less to do with the volume of information and more with decisions.

The US-based expert is the author of The Myth of Multitasking: How ‘Doing It All' Gets Nothing Done and Invaluable: The Secret to Becoming Irreplaceable, and has appeared in Time magazine and Forbes.

He says, "Think of it this way. If I had five TVs switched on and I try to watch all, one might say I'm experiencing information overload. But the problem is I'm not making a conscious decision to watch one [programme]. While the term [information overload] is used more commonly, I prefer decision overload. People decide to do too many things at the same time thus overwhelming them."

Could Crenshaw be correct? After all, he has helped CEOs and employees worldwide increase productivity both at business and personal levels. He is also a PhD student studying competitive intelligence and information overload.

Maybe if I chose fewer mediums, I wouldn't have to carry these knotty information threads and maybe I would be able to manage this mental jumble better.

Lesa Becker, the director of organisational learning for a renowned healthcare system and a PhD candidate at the University of Idaho highlights this issue, hinting that information overload has to do with our limited capacity to handle information effectively.

She says, "It isn't the volume of information that is the problem; it is the quality of it and our limited human capacity to process it effectively. There are multiple factors that contribute to information overload. My research [Eppler and Mengis] focuses on five: the characteristics of the information we are required to process; the types of tasks we perform with the information we receive; the technology we use to assist us in performing those tasks; personal or human factors that help or hinder our ability to manage information; and organisational factors that impact our effectiveness."

If I agree with Crenshaw and Becker, will I be able to untangle my mental jumble? Before I attempt to, let me first trail those random threads to its source.

Channels of information

Most of the threads I picked trailed to an electronic medium, a place where most get sidetracked. The internet, in particular, with its infinite choices. It is also the place I try not to surrender to hyperlinks. Anyhow this pattern points to the culprit - choice.

Rather like the jam experiment that went on to prove that the wider the choice, the harder it is to make decisions. (This is contrary to conventional economic wisdom that propounds the more choices consumers have the more likely they are to buy.)

The experiment, credited to Sheena Iyengar, a US-based professor of psychology and author, found that people bought ten times less jam when presented with 24 choices than when limited to six.

Or in the way Malcolm Gladwell puts it in Blink, his book about the power of thinking without thinking. He wrote: overloading the decision makers with information makes decision making more difficult.

To be a successful decision maker, we have to edit. If you're given too many choices, you are forced to consider much more than your unconscious is comfortable with. And so it is the case with information channels. It is hard to choose.

We have too many choices, each with repercussions. Each quantified by a certain level of intrusiveness. An email on travel offers, for instance, may distract you for a few minutes. A tweet could inspire a 30-minute dialogue. A chat on a social networking site could occupy you for hours.

In this context, Becker accuses instant messaging as the most serious offender. She says, "The most intrusive information channel is instant messaging via texting, twittering or other forms. One of my research participants said, ‘People are in constant interrupt mode at work, bombarded with phone calls, drop-ins and email… It's almost like everyone has Attention Deficit Disorder [ADD].' Personally, I prefer the acronym eADD or Electronically-induced Attention Deficit Disorder."

She qualifies email as the next most intrusive information channel. "Especially when you leave your inbox open all day rather than check it once or twice [a day]," says Becker, adding that the internet is next on the descending scale of intrusiveness.

When she was preparing for our interview, she did a Google search on the subject. "In .22 seconds, I had more than a million hits on the topic. Just for fun, I also did a Bing search and obtained 15.2 million results. That's more than 15 million… It would have taken me years to get through all those references," she says, admitting that the internet is a wonderful source of immediate information, but the quality of information is at times questionable and the quantity mind-boggling. "Print-based information isn't as intrusive because it is easier to filter," she says.

Still, knowing what is or isn't intrusive may not solve the problem of information overload. We need to understand how to navigate through this minefield of hyperlinks and the electronic ticker tape of information.

According to Crenshaw, the key is to be very cautious about the kind of intrusive sources of information we allow into our life.

He says, "There are certain sources of information that are passive; these include mobiles, text messages, interruptions from people in our office and even leaving the TV and radio on in the background. It is wise to restrict these passive sources."

In other words, these expertsseem to think that we should err onthe side of caution to deal with information overload.

Overburdened by information

Ever since American technologywriter Nicholas Carr raised the poignant question "Is Google makingus stupid?" in an article for TheAtlantic, he has given us reason to worry about the damaging effects of using the internet and electronic mediums in general. In his book, The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, Carr talks about how technology is destroying our powersof concentration.

Rightly so.

After combing through my collection of information threads, I ought to give that report about the Buzz Lightyear look alike carrot a little more importance. Perhaps horticulture should look into the science and art of decorating roots apart from topiary. (Maybe we could genetically modify the humble spud to grow into something that is friendlier to make crisps!)

Back to the subject of information overload, the truth is much of what we pick, we do in a cursory manner, often leaving little or no time for deep thought. Further, this cursory approach leaves us too distrait to work or return to our previous tasks.

The worse effect though is our tendency to depend on technology to retrieve information because we think, "What is the point in memorising when it is stored a click away?" This of course is my opinion.

Crenshaw believes that the most negative effect of information overload is the tendency to multitask. He says, "Multitasking results in loss of time, decrease quality, increased stress and relationship damage among others."

That is why he places emphasis on the term ‘decision overload'. He says, "Information in itself does not make someone smart any more than memorising dates and numbers makes someone a college professor.

What matters more is how much of an expert in a particular field you are. In a world of information overload, it's more important to become a specialist, not a generalist. Everyone can be a generalist today. Anyone can find an answer in Google in a matter of seconds."

Thus I've come to understand that the problem of information overload is quality, not quantity. If I had to quote someone, I would choose American futurologist Jamais Cascio. He said, "The trouble isn't that we have too much information at our fingertips, but that our tools for managing it are still in their infancy."

Could this be true?

Becker imputes the problem of information overload to Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs). She has formulated a series of recommendations to help leaders and organisations manage information overload. She says, "ICTs contribute to the problem of information overload. ICT tools encourage multitasking, which cognitively, we aren't able to do. For example, we can breathe and type on a computer because breathing is an automatic process. But we cannot type on a computer and listen to a conference call without missing important information. That is why texting and driving is so dangerous. If your brain is busy trying to type in a text message, not only are your eyes off the road, your brain is occupied and you may not task switch quick enough to see a traffic light change."

Crenshaw on the other hand disagrees with Becker's view, stating that it is not technology, but our lack of skills and understanding of how to use that technology that is the problem. He says, "In my training, we spend the majority of time teaching how to better use the technology that they [clients] have, but didn't know how to use."

Ironically then technology is both the problem and the solution.

Let's lighten the load

The aforementioned statement makes me think of how Gmail launched a priority inbox service that ranks email based on perceived importance. How does Google do this? Through a set of algorithms that analyse your email behaviour and use this information to rank emails.

It would be nice if algorithms can ease the burden of trawling through hundreds of emails and links and simply give us what we want. I certainly didn't want to know about the American football player's hair being insured or a health minister's views on obesity.

In other words, it would be great if technology, the perpetrator, becomes the rescuer.

On this, Crenshaw and Beckerhave different approaches.

Becker says, "I do not believe technology will rescue us primarily because technology products are designed by companies with the motive of making money. I haven't seen information or communication products that are designed with the primary goal of making the end-user's life easier. Technology contributes to the problem. The answer lies in rethinking the business practices of our organisations."

Crenshaw says, "The solution isall about time. There are only 60 minutes in an hour. The importanceof budgeting our time becomes critical. We must make a conscious decisionon what information we allow intoour lives."

He advises people to focus on their Most Valuable Activities (MVAs). He says, "MVAs are the things that you do better than anyone else. When you focus your actions on your MVAs, this presupposes that you must focus your research, your understanding and your information inputs on a particular set of subjects. So it's in the choices that we make that we will still remain unique, even in a situation where there is perfect information. When you budget time, you focus on certain activities, and when you're researching things, you're only researching things that are critical to your MVAs."

I think I'll leave you with this and go discover my own MVAs.

Stats

- 38 per cent of managers waste substantial amounts of time just looking for information.

- 47 per cent of respondents said that information collection distracts them from their main responsibilities.

Info courtesy: The Marc Fresko Consultancy

- 1.5 billion gigabytes of storage is what the world's total yearly production of print, film, optical and magnetic content would roughly require. This is the equivalent of 250 megabytes per person for each man, woman and child on earth.

Info courtesy: University of California, Berkeley

- 62 per cent of professionals report that they spend a lot of time sifting through information to find what they need.

- 68 per cent of professionals wish they could spend less time organising information and more time using the information that comes their way.

- 85 per cent of professionals agree that not being able to access the right information at the right time is a huge time-waster.

Info courtesy: LexisNexis Workplace Productivity Survey/ WorldOne Research

- 65 per cent is the yearly growth rate of the amount of information created in enterprise, paper and digital combined.

- 15 per cent reduction in the time wasted in dealing with information overload could save a company with 500 employees more than $2 million a year.

- 60 per cent of respondents rated dealing with too many different types of information a bigger problem than dealing with too much information.

- 75 per cent of workers in more than 1,000 large organisations said they suffered from information overload in a global survey IDC conducted last year. Of those, 45 per cent said they were overwhelmed.

- 1.7 million links will show up when you search for the term ‘information overload' on Google.

- More than 40 per cent of digital documents get printed and more than half of printed documents get keyed into computer applications. The boundary between paper and digital information is porous.

- US workers spend more than 25 per cent of their time dealing with interruptions and distractions according to the company Basex, which studies information overload and hosts the Information Overload Research Forum.

Info courtesy: Xerox Corporation/ IDC

Did you know?

Lesa Becker's dissertation, Information Overload's Impact on Organisational Leaders: Learning How to Thrive in the 21st Century, is available for purchase from ProQuest.

BTW

Dave Crenshaw's often humorous and entertaining approach always hits right on the head with audiences. His speeches around the globe are described as life changing.

Did you know?

Sheena Iyengar, author of The Art of Choosing, is considered an authority on ‘choice'.

Deal with it

According to Dave Crenshaw, we can overcome information overload. Here's how…

Reset the frequency of interruptions. For example, if you are going to be meeting someone, turn off your mobile. Have a set time in your schedule to check it.

Turn off passive notifications like email, voicemail, text messaging, etc. Don't let these gadgets rule your life. Instead, have a schedule for yourself when you check those things so you can be the one who is in control of technology.

Make a list of three to five topics that you are going to choose to be an expert on. Then ruthlessly eliminate your exposure to information other than those three to five sources. I'm not saying don't read the news, I am saying you don't need to have ten different magazine subscriptions or visit ten different blogs.

Find decision leaders or experts you trust. For example, when you have to decide on a product, listen to decision leaders; they can shorten the decision-making for you and allow you to leap over information overload when you choose to attach yourself to them.