This week, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) is meeting in Vancouver. As is tradition by now, the Tuesday lunch slot was used by the Internet Society (ISOC) for a panel discussion about an issue important to the future of the Internet. Today's topic: the state of IPv6 after the World IPv6 Launch two months ago, executed under the optimistic title "Life with a bigger Internet—World IPv6: Launched!"

The World IPv6 Launch on June 6 was an industry-wide effort to get websites to enable IPv6 permanently, to have participating Internet Service Providers turn on the new protocol for at least one percent of their users, and for home router vendors to enable IPv6 by default. All of this is needed because the current version 4 of the Internet Protocol is quickly running out of addresses.

Leslie Daigle, ISOC's chief Internet technology officer, stressed that World IPv6 Launch was not about turning off IPv4—that won't happen "anytime soon." Instead, websites added IPv6, making them reachable for both IPv4 and IPv6 users. "The important takeaways are that IPv6 is launched, and that this was a phenomenal collaborative industry effort." And: "it's not too late for access providers to sign up."

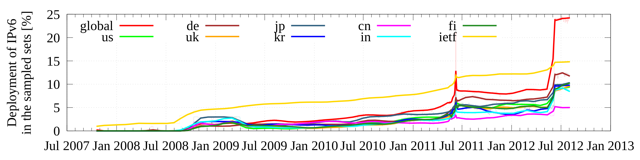

Mat Ford, technology program manager at ISOC, presented a variety of IPv6 measurements. The amount of IPv6 traffic per network (including both content networks and ISPs) varies enormously, with more than 17 percent at French ISP Free and a very surprising nearly 60 percent at Virginia Tech and Louisiana State University on the one hand, and a few tenths of a percent elsewhere, such as Time Warner Cable. And many networks haven't enabled IPv6 at all. All statistics saw a big jump in IPv6 deployment and/or traffic on June 6, and then typically also a steady increase after that. Currently, 25 percent of Alexa's global top 1000 websites have an IPv6 address in the DNS.

George Michaelson from APNIC, the Regional Internet Registry that hands out IP addresses in Asia and the Pacific, presented results from a creative way to measure IPv6 usage: they placed an ad. In order to get a decent number of clicks, the ad's flash code had to be shown to lots of users, which allowed Michaelson to observe many unique IP addresses. Interestingly, countries that are otherwise fairly similar may exhibit very different IPv6 adoption rates. For instance, they measured only 0.098 percent in Canada, but 1.3 percent in the United States. The explanation for this is that one or two big ISPs with a decent number of IPv6 users can easily inflate the number for an entire country.

John Brzozowski, chief architect at Comcast, talked about Comcast's IPv6 deployment. Currently, two percent of Comcast's users are on IPv6, and about one percent of its traffic is IPv6—until the Olympics, that is, which increased the number to six percent, thanks to YouTube's live streaming of the event. When a user has IPv6, as much as 40 percent of their traffic can be IPv6, mostly because of YouTube, Netflix, and the iTunes App Store.

Lee Howard, director of network technology for Time Warner Cable, explained that the World IPv6 Launch goal of one percent IPv6-enabled users was more ambitious than it seems. In Time Warner's network, about half of the cable modems and 30 percent of the Cable Modem Termination Systems (CMTS) in the network support IPv6. About half of the users have an operating system that supports IPv6—nearly 50 percent are still on Windows XP. But 85 percent of customers have a home router between their cable modem and their computer(s), which typically doesn't support IPv6. So the total number of Time Warner users that can actually use IPv6 is only 0.5 x 0.3 x 0.5 x 0.15 = just over one percent.

Google's Lorenzo Colitti talked about remaining issues now that IPv6 has been rolled out in Google's network. There are networks with broken IPv6 setups which, rather than fixing the problem, simply filter IPv6 addresses in the DNS. Colitti: "Filtering of AAAA records is not a good idea because, among other things, it masks the problem. You can't tell when the problem is solved." In some cases, especially in Japan, two networks both have IPv6, but they don't interconnect directly or through a bigger ISP, so they can't reach each other over IPv6.

Colitti warned that IPv6 isn't in "self-sustaining mode" yet: if the additional cost of IPv6 is substantial, businesses may choose to launch a new service on just IPv4 first. But the good news is that IPv6 adoption grew by 150 percent over the last year. If that rate holds up, half the Internet will be on IPv6 in 2018, with the entire Internet caught up a year later. (Of course Asia has been out of IPv4 address for a year now, Europe will run out within two or three months, and North America within several years).

Erik Nygren, chief architect at Akamai, said that Akamai saw 19 million different IPv6 addresses at World IPv6 Launch, no less than 67 times the number seen at last year's World IPv6 Day. The traffic was an impressive factor 460 higher at 3.8 billion requests. The reason: more IPv6 users, and more content on IPv6. A total of 86 percent of Akamai's IPv6 requests came from just three networks: Verizon Wireless (which has a lot of IPv6-enabled Android devices on its LTE network), AT&T, and Comcast in the US, as well as RCS & RDS in Romania, Free in France, and KDDI in Japan. The geographic distribution of those requests is rather uneven at 71 percent from the US, 21 percent from Europe, 5.1 percent from Asia, and only 0.4 percent from the rest of the world. (See Akamai's World IPv6 Launch infographic [PDF]).

At the end of the panel session, Leslie Daigle asked the panel whether someone who only has IPv6 can be considered to be "on the Internet" at this point. No panel members were prepared to answer in the affirmative just yet, but she was encouraged to keep asking the question. The good news is that IPv6 is finally getting some traction. The bad news is it's not happening nearly fast enough to avoid an ugly transition.

reader comments

39