The Internet may run on love; thanks to Facebook, though, it also runs on like. Or, more specifically, on Like.

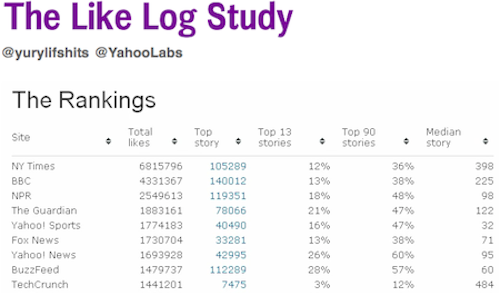

That’s made clear in a collection of research, released last night, that traces the Facebook effect when it comes to online news. Conducted by Yury Lifshits under the auspices of Yahoo Labs, the study traces three months’ worth of Facebook Like stats for over 100,000 stories at 45 large news sites, from The New York Times and the Guardian down to paidContent and Poynter. (The research takes advantage of the fact that Facebook allows anyone to collect the total number of Likes for any URL.)

The Like Log’s findings? In terms of overall popularity (total Likes), The New York Times is “the leader of social engagement,” with some 2.3 million Likes per month, 400 Likes for a median story, and 13 articles in the top 40 most-Liked overall. In terms of individual stories, the Wall Street Journal’s excerpt of Amy Chua’s (in)famous Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother — Journal headline: “Why Chinese Moms Are Superior” — comes out on top, with 340,000 Likes.

A Like button, of course, is a horribly blunt instrument when it comes to gauging the motivations of the Likers who click it. We don’t know for sure why all those people clicked the Like button for Chua’s excerpt; we can figure, though, that not all of them were doing so out of a spirit of “Yeah! Chinese Moms are better!” Despite Facebook’s analytics improvements to its most ubiquitous sharing plugin, data gathered via the Like button carries an implicit caveat. Particularly after the demise of the neutral “Share” button, it doesn’t follow that we actually like what we, you know, Like.

That being said, though, the info Lifshits has gathered is instructive, and well worth exploring from a news-publishing perspective. (Particularly in light of a recent study finding that a Facebook Like, in dollar terms, is worth about four times a Twitter follow.) Some general highlights:

When it comes to social engagement, Lifshits says, it’s all about the short head of the long tail. “These days, many editors believe that publishing frequency is the key,” he notes in a video explaining his research. But “our data shows the opposite: The top stories affect the majority of user activity. As you see from our measurements, NPR, the Guardian, or Yahoo News can get half of their total engagement by publishing only one story per day.”

That’s fascinating. And despite the important caveat — that Lifshits’ data set consists of 45 highly trafficked news sites, and that the one-story-for-50-percent-of-engagement trend might not hold for smaller sites — it translates into classic advice made new for the age of digital news: Given a choice, opt for depth over breadth. (That’s advice that’s being tested in, among other laboratories, Gawker: In undoing the a-post-is-a-post framework of the blog for a more editorially driven news product, Gawker is self-consiously adopting the big story double-down.) Of course, for outlets motivated by more than traffic alone — outlets that have a public interest, if not a financial stake, in serving audiences with a breadth of news — the approach has to be used strategically. But the share data for the Big 45 reflect what many news publishers see anecdotally: that one big story, in terms of engagement and brand identity and all the rest, can be worth much more than a slew of smaller ones.

So, then, what makes for a Big Story? Lifshits notes that, of the 40 most-Liked stories of the past three months, many are related to “lifestyle, photo galleries, interactives, humor and odd news.” Four of the articles in the top 40 are about “actual political news”; three are about celebrities. But “the most common type of hit stories is opinion/analysis.”

That’s unsurprising; opinion and analysis have been driving journalism’s circulation since long before Thomas Paine put quill to paper (and, hey, since long before some Sumerian gadfly put wedge to clay). But, then, are the stories here really just about “opinion/analysis”? That captures some of it, sure; but the shareability factor, I think, is about more than the simple fact of people liking analysis. Arguments, importantly, aren’t just presented opinion or POV-driven narrative; they’re meant to sway and persuade — and, in that, they’re implicit invitations to discussion and interchange.

Writing about the implications of Facebook’s Like/Share/Recommend wording, Josh noted that the most-shared content at the Lab tends to be the stuff that engenders — in the emotional sense — arousal. “Content that you can imagine someone emailing with either ‘Awesome!’ or ‘WTF?’ in the subject line gets spread,” he wrote. Part of that is that emotion sells, and encourages us to share. Part of it, too, though, is that it encourages us to create. The best stories — the most inherently share-worthy stories — are the ones for which it would be almost weird to email them to someone — or tweet them to someone, or whatever — without an introductory “WOW” or “WHOA” or “WTF.” In our Twittery world, a story about, say, porpoises rescuing Dick Van Dyke after he fell asleep on his surfboard (#12 on Lifshits’ most-Liked list) isn’t just a great (and wonderfully weird and awesomely hilarious) yarn. It also screams for reaction. It seems almost created for commentary.

The stories on Lifshits’ most-Liked list run the gamut: from hard news to soft, from reporting to analysis, from funny stories to simply weird ones. But what they have in common, I think, is that “WHOA” factor — that inherent remarkability that taps into that primal part of ourselves that makes us want to spread the word. And, more to the point, that makes us want to add to the word. As hard-wired as we are for sharing, after all, we’re equally hard-wired for creating. And it could be that the most inherently shareable news is the news that extends argument into invitation: that compels us, in our own little way, to add our two cents. And that could be so even for news filtered through a mechanism as simple — and an instrument as blunt — as a Like button.