The Vim text editor was first released to the public on November 2, 1991—exactly 20 years ago today. Although it was originally designed as a vi clone for the Amiga, it was soon ported to other platforms and eventually grew to become the most popular vi-compatible text editor. It is still actively developed and widely used across several operating systems.

In this article, we will take a brief look back at the history of vi and its descendants, leading up to the creation of Vim. We will also explore some of the compelling technical features that continue to make Vim relevant today.

Prehistory

The vi text editor was originally created in the late ’70s by Bill Joy, an early BSD developer who later went on to cofound Sun Microsystems. The original implementation of vi was conceived as an interactive “visual” mode for an ed-like line editor called ex. It was developed at first on an old ADM-3A terminal, about a decade before computer mice became ubiquitous. Users relied on commands and keyboard-based navigation to interact with the editor.

The limitations and idiosyncrasies of the ADM-3A influenced some of vi’s most distinctive characteristics. For example, vi was programmed to use the h, j, k, and l keys for directional navigation because the ADM-3A keyboard had arrows printed on the keys with those letters. Although it was an accident of history, the hjkl navigation model in vi proved to be enormously efficient. The combination of those letters has become practically iconic among vi users. The navigation scheme is used today in a variety of other applications, including Gmail and the official Twitter client for Mac OS X.

The vi editor became an inseparable part of the UNIX landscape. Joy bundled it with BSD and ATT incorporated it into System V. The core functionality and behavior of vi was later specified in the POSIX standard, which led to the inclusion of the text editor in many of the major UNIX systems.

The vi clones, which began to emerge in the late ’80s and early ’90s, were widely adopted due to more permissive licensing. Joy’s vi implementation was based on the original ATT version of ed, which meant that the code was not freely redistributable. It could only be used by parties that had a UNIX license from ATT.

The first two prominent vi clones were Stevie and Elvis. Stevie, the ST Editor for vi Enthusiasts, was originally developed for the Atari ST in 1987 and ported to UNIX the next year. It was somewhat primitive but attracted a modest following. Elvis, which was first released in 1990, was more sophisticated and was designed to offer more functionality. Elvis was the first vi clone to introduce support for syntax highlighting.

Although Elvis still has some users and remains popular in the Slackware community, it hasn’t seen a major update since 2003. Elvis replaced Joy’s vi in the original 386 port of BSD, but the BSD developers later produced a new clone called nvi that was intended to more closely match the behavior of Joy’s implementation. The nvi editor is still shipped today by the BSD family of operating systems.

History

The earliest version of Vim was developed on the Amiga by Bram Moolenaar in 1988. Moolenaar was dissatisfied with the vi clones that were available for the Amiga platform and set out to make one that came closer to matching vi’s feature set. He based his new editor on Stevie, which he has said was the best Amiga-compatible vi clone at the time.

The first version of Vim that was released to the general public was 1.14, which was published on November 2, 1991. It was distributed on Fish Disk #591, one of the disks in Fred Fish’s Amiga freeware collection. Following its public debut, users began contributing patches.

“A long time ago I got myself an Amiga computer. Since I was used to editing with Vi, I looked around for a program like Vi for the Amiga. I did find a few so-called ‘clones’, but none of them was good enough; so I took the best one, and started improving it. At first the main goal was to be able to do all that Vi could do. Gradually I added some additional features, like multi-level undo,” Moolenaar wrote in the first issue of Free Software Magazine, back in 2001. “When I started working on Vim it was just for my own use. After some time I got the impression it was useful for others, and sent it out into the world. Since then I’m working more and more on making the program work well for a large audience. It’s fun to create something useful. Also, there is a nice group of co-authors and power users, which is very inspiring.”

Moolenaar drafted his own loose copyleft license for the software. The license grants the user broad freedom to use, distribute, and repurpose the code, but gives the maintainer the right to ask for improvements to be contributed back to the project. Some clarifications were added to Vim’s license in the version 6.0 release to ensure compatibility with GNU’s General Public License (GPL).

Vim is an open source software project, but it’s also charityware. Moolenaar helped establish a foundation called ICCF Holland that works to support to a children’s center in Uganda. He encourages users to consider making a donation to ICCF Holland or the Kibaale Children’s Fund. He serves as treasurer of the foundation and visits the site in Uganda nearly every year to monitor the center’s progress.

The name “Vim” originally stood for Vi IMitation, but it later became Vi IMproved. The name was changed in 1992 when version 1.22 was released with compelling new features and a UNIX port. It gained support for multiple buffers in version 3.0, which was released in 1994. Version 4.0 in 1996 introduced a graphical user interface, version 5.0 in 1998 added syntax highlighting capabilities, and version 6.0 in 2001 added support for vertical window splits and a plugin system that simplified script loading.

Many, many other features were added along the way. Vim has been ported to numerous other platforms, including Linux, BeOS, Windows, Mac OS X, and QNX. Although Vim was originally designed to be used in a terminal, there are several graphical frontends built with various user interface toolkits that add conventional menus, toolbars, and scrollbars.

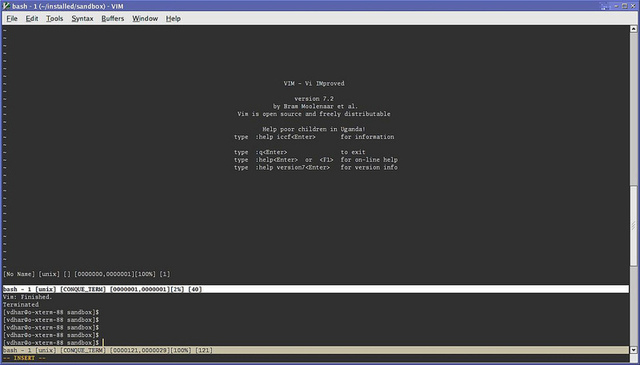

The latest major release of Vim was version 7, which was released in 2006. It introduced some particularly significant features, including native support for spellchecking, an autocompletion system, a tab interface, and undo branches. The most recent minor version update was version 7.3, released last year, which introduced a persistent undo feature and support for Python 3.

Vim today

Due to the popularity of the clones, the name “vi” has become a general term that is used colloquially to describe any member of the family of vi-compatible editors that more-or-less support the features that are specified in the POSIX standard. Today, direct derivatives of Joy’s vi are generally only used in a handful of commercial UNIX environments. All modern BSD and Linux systems include a clone rather than the original.

The BSD distributions still mostly ship nvi, but Mac OS X and the vast majority of Linux systems come with Vim. In most cases, the vi command has been configured as a symlink that launches Vim directly, or a script that launches Vim with strict vi-compatibility enabled. If you have used the vi command on a Linux system at any time in the past decade, it’s very likely that you were using Vim.

Unlike the other prominent vi clones, Vim is still actively developed and has a large base of contributors. New features are still being developed and added to the text editor every year, making it even more powerful. Moolenaar also still serves as the chief maintainer and does much of the work to make sure that contributed patches function well and are integrated properly.

Why people still use Vim

The notion of using a modal command-oriented editor may seem a bit anachronistic at first glance, but Vim’s rich feature set and deep extensibility have made it an enduring choice among advanced computer users. It’s still a highly popular editor, especially among computer programmers, Web developers, scientists, and system administrators.

The full scope of Vim’s advantages are difficult to articulate to users who are unfamiliar with the editor. Although a full explanation of how Vim works is beyond the scope of this article, the following is a small assortment of useful features:

-

Flexible multiple document interface: In Vim, your files and unsaved documents are referred to as buffers. The editor gives you a tremendous amount of control over how your buffers are displayed on the screen. You can horizontally and vertically split the window as many times as you want so that you can view many buffers at the same time. You can even have the same buffer displayed in multiple splits, which lets you view separate parts of the same document simultaneously. You can also optionally organize sets of split layouts into tabs. Layouts and state can be preserved by saving a “session” and restoring it later.

-

Modal editing with sophisticated keyboard shortcuts: Vim has separate interaction modes for text input and text editing. Insert mode behaves largely as you would expect a regular text editor to work—commands are performed with conventional keyboard shortcuts and characters are appended to the buffer as you press the associated keys. In the “normal” mode, however, sequences of key presses perform commands. The most useful commands allow you to quickly navigate and manipulate the text in the buffer. You can extensively customize the behavior of the bindings to create custom shortcuts and commands.

-

Multiple clipboards: Instead of a conventional clipboard, Vim stores copied text with a mechanism that it calls registers. There is a default register that is used to store text that is copied by the standard yank and delete operations, but the user can also indicate a specific register in which they want to store text when they cut or copy. This effectively acts like a clipboard multiplexer. The contents of the registers persist between uses of Vim, which means that they are preserved when you quit and will still be there when you open the editor again.

-

Macros: Vim has a macro system that allows you to record keypresses for later playback. Macros are trivially easy to create from the keyboard and can consist of operations across multiple Vim modes. Macros are stored in registers, just like the clipboard items. As such, they can also persist across uses of the application.

-

Extremely powerful search capabilities: Vim has some very sophisticated tools for automated search and replace, including extensive support for regular expressions. It also has a built-in version of the

grepcommand, which integrates with Vim’s enormously convenient quickfix feature—a special buffer that shows you a list of results and allows you to conveniently jump between them. -

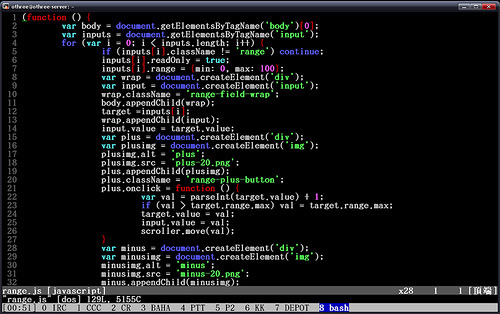

Extremely rich extensibility: Vim is prodigiously scriptable and highly conducive to automation. It has its own native scripting language with container types, a unique variable scoping model, and a bunch of useful Vim-specific functionality. It also has built-in scripting engines and bindings that allow it to be customized via numerous mainstream programming languages, including Perl, Python, Ruby, Tcl, and Lua. Vim can also be extended to add syntax highlighting for additional languages or create custom color schemes. Users widely share their scripts through various online repositories and package them into plugins. As we have previously demonstrated, installing a few simple plugins and scripts can give Vim many of the advanced capabilities of an integrated development environment.

-

Portability: Vim will work almost everywhere that you do. Vim is widely used on Windows, Linux, and Mac OS X and is available for many other platform. Users can run it from the terminal or operate it with a native graphical interface on all three major operating systems. Many system administrators value Vim because it gives them a productive text editing environment on practically any remote Linux or Mac OS X system that they access through the terminal via ssh.

Conclusion

Vim has been my editor of choice since 1998, about a year after I started using Linux as my main desktop operating system. I’ve used it to write several thousand articles and many, many lines of code. Although I’ve experimented with a lot of conventional modern text editors, I haven’t found any that match Vim’s efficiency. After using Vim nearly every day for so many years, I’m still discovering new features, capabilities, and useful behaviors that further improve my productivity.

Vim has aged well over the past 20 years. It’s not just a greybeard relic—the editor is still as compelling as ever and continues to attract new users. The learning curve is steep, but the productivity gains are well worth the effort.

Do you remember your first experience with vi or Vim? In honor of the venerable text editor’s 20th anniversary, share your memories and favorite features in the discussion thread.

reader comments

151