Editor’s Note: David M. Perry is a freelance journalist focusing on disability issues. He is author of the new book “Sacred Plunder” and is an associate professor of history at Dominican University. He writes regularly at the blog How Did We Get Into This Mess? Follow him on Twitter. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

David Perry: Children with disabilities are more likely to be restrained

A "cult of compliance" threatens the well-being of our children, he says

The whimpers turn into cries of pain as the cuffs go around the child’s biceps. He’s a small Latino boy, 8 years old, 3½ feet tall and 52 pounds. He has ADHD. The school resource officer says, “You can do what we asked you to, or you can suffer the consequences.”

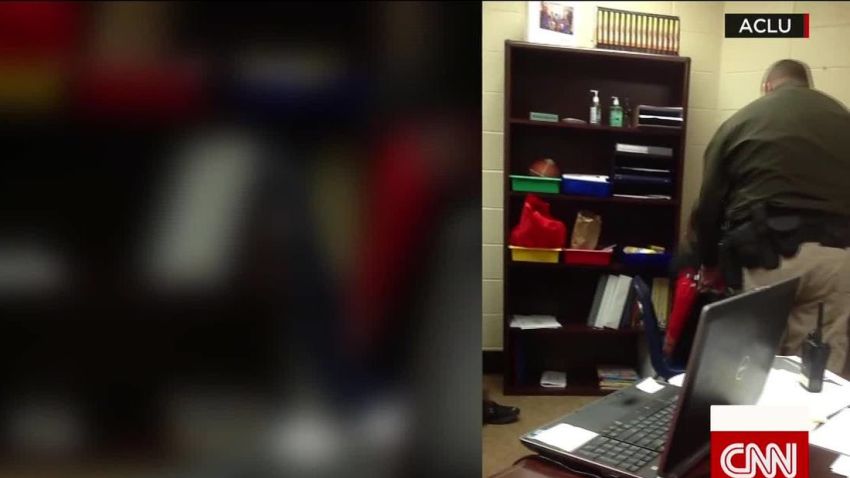

“Ow, that hurts,” sobs the boy. The officer appears to yank the chain to force the boy into a chair facing the corner, and he and his partner loom over the child. “Please,” the boy says. But more than seven minutes of sobbing later, he is still cuffed, and a voice says, “Stop the video.”

The American Civil Liberties Union and two families have filed a federal suit against the officer and the Kenton County Sheriff’s Office in Kentucky on behalf of the child, identified in the video as S.R., and a second child, a 9-year-old African-American girl referred to as L.G. Both children, the complaint alleges, were illegally restrained. In one encounter, it is claimed, L.G. was handcuffed in such a way as to deliberately cause pain in pursuit of compliance. Both children have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. L.G. also has post-traumatic stress disorder. The ACLU says this type of mechanical restraint violates the Americans with Disabilities Act and the children’s core constitutional rights.

The absolute worst thing about this video is that without it, almost no one would care. The use of violent restraint and seclusion to enforce compliance on children with disabilities, especially children of color with disabilities, is a well-documented problem. In 2009, the Government Accountability Office reported on widespread abuses, and Secretary of Education Arne Duncan called for action. And yet, if anything, the problem is only getting worse.

Here are some numbers, based on the most recent data (from 2011-12). According to Claudia Center, senior staff attorney of the ACLU’s Disability Rights Program, there are more than 52,000 students with disabilities restrained every year, 4,000 of them in “mechanical restraints’ (handcuffs and shackles). That’s over 20 times the rate that children without disabilities are restrained. Within that population, children of color are far more likely to be restrained than white students with special needs.

Restraint leads to criminalization, the school-to-prison pipeline and lives torn apart by incarceration. A recent study by David Ramey, assistant professor of sociology and criminology at Pennsylvania State University, argues that teachers are far more likely to summon police when dealing with black students with behavioral problems than with white students. In our school system, racism and ableism cruelly intersect.

School resource officer sued for allegedly handcuffing children with ADHD

The officer is not solely to blame in cases such as these. In fact, he should never have been involved in the first place. According to the complaint, the two children in question were having trouble sitting still and following directions, so the teacher got the administration and the officers involved. That was a mistake. For a child with ADHD, of course, inability to remain still is fairly typical. Barb Trader, executive director of TASH, a nonprofit group that advocates for people with disabilities, says that the worst thing you can do to children who are having trouble regulating their behavior is to try to use punitive discipline. Instead, you have to work with each child individually in order to “understand what’s causing the behavior, help them understand how they are feeling and what to do about it before a behavior became disruptive.”

Just like the problem of punitive restraint, positive methods of working with children with disabilities are nothing new. “They (teachers) should learn this in college!” Trader says. Too many school districts, though, have embraced zero tolerance, rather than well-documented techniques like Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports to address behavioral needs. In the meantime, countless children are arriving at school diagnosed with various disabilities, too often struggling with trauma, and behaving in ways that demonstrate they need help. Yet instead of receiving it – especially if they are nonwhite and poor, or stuck in big, poorly resourced classrooms – they get handcuffed, and too frequently they are charged with crimes.

The ACLU, along with other groups and these two brave families, are ready to try to change the dynamic by establishing a new, stronger legal precedent against restraint. “This is relatively new legal ground,” Center says, as most other cases like this have been settled quietly for cash settlements and with confidentiality agreements. The goal here is to effect systemic change through the courts. Center says it’s almost never necessary to restrain children, and in those rare cases where it might be appropriate, handcuffs are always the wrong answer. She points to a new policy in Jackson, Mississippi, which uniformly bans the use of handcuffs for children under 13.

Throughout the video, the officer keeps asserting that it’s the child’s fault if he’s in pain. All the child has to do is comply with commands, sit quietly, stay still, stop twitching his legs, and he’ll be released. But when a child has ADHD, that may literally be impossible, especially under the traumatic tension of the moment.

I keep coming back to the officer’s assertion that it’s the child’s fault that he’s in pain. For the officer, lack of compliance appears to justify an aggressive response. Too many teachers, administrators, school resource officers, cops, government officials and even parents seem to agree. This cult of compliance, as I call it, threatens the well-being of our children, especially those with disabilities who literally may not be able to comply.

No child, in any circumstance, should be physically abused for failure to obey orders or for disrupting class. Pain doesn’t teach a child anything but that they should be afraid: afraid of police, afraid of their teachers, afraid of their school. Is that what we want?

Join us on Facebook.com/CNNOpinion.

Read CNNOpinion’s Flipboard magazine.