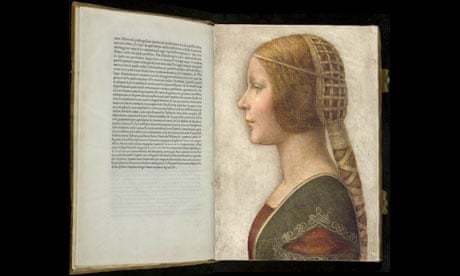

The auction house Christie's dismissed it as a 19th-century pastiche by an unknown German hand, while one gallery director privately condemned it as a "screaming 20th-century fake". Now a leading art historian, who has long believed that this drawing of a young woman is a lost masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci, has unearthed what he is convinced is conclusive proof. Martin Kemp, emeritus professor of art history at Oxford University, has identified the drawing as a missing sheet from a 15th-century volume linked to Leonardo's great patron, the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza.

Last year, Kemp provisionally identified the sitter as Bianca, the duke's illegitimate daughter, who died a few months after her marriage at the age of 13. This identification was supported by the title page of the Sforziad, a volume celebrating the Sforzas; symbols in the book show that it was a wedding gift.

"Assertions that it is a forgery, a pastiche, or a copy of a lost Leonardo are all effectively eliminated," Kemp told the Guardian. Earlier this year, he embarked on what he describes as a "needle-in-a-haystack" search for a 15th-century volume with a missing sheet. A clue lay in the stitch-holes along the portrait's left-hand margin, suggesting it had been torn from a luxury-bound volume. But the chances of this volume surviving 500 years were remote, and the chances of it being found even remoter.

Against the odds, Kemp tracked the volume down, to Poland's national library in Warsaw; the stitch-holes are a perfect match for those on La Bella Principessa, a portrait in ink and coloured chalks on vellum. It is overwhelming evidence, Kemp says, that the portrait dates from the 15th century – and not the 19th century, as Christie's thought when it sold it in 1998 for £11,400 (it could fetch £100m as a Leonardo).

Kemp travelled to Warsaw with a specialist who has undertaken scientific analysis of the Mona Lisa, scanning beneath paint layers. Recalling the moment they opened the volume, Kemp says: "Yes, lo and behold, we could identify that there was a page clearly removed. The stitch-holes matched, the vellum matched. It is indeed 1496, it is indeed Bianca and indeed for her marriage. It's uncanny. You could say: 'Stitch holes are always the same distance apart.' But the irregular stitching was spaced by eye, not precisely measured."

Technical analysis confirmed that "the vellum of the portrait closely matches, in all respects, the physical characteristics of the remaining sheets", Kemp says. "Vellum sheets are made by an elaborate process of shaving a calf, kid or lambskin to a desired thickness. Even in a batch of sheets the thickness will vary. The thickness of the portrait parchment is entirely consistent with the Warsaw book's folios." The volume even bears an incision where the blade that removed the sheet slipped.

Kemp unveiled the drawing as a lost Leonardo last year, an attribution supported by several scholars, including Leonardo expert Carlo Pedretti. But Christie's dismissed the attribution, fighting off a compensation claim by Jeanne Marchig, on whose behalf they had sold it.

The doubters include Jacques Franck, a Leonardo consultant to the Louvre. While the drawing has undergone some restoration, he believes there are anatomical mistakes between the neck and bust. Others have argued that there are no other Leonardos on vellum, although there is evidence of his interest in its use.

The chief opposition has come from New York experts, who did not identify the drawing as a Leonardo when it was in the hands of Christie's New York; and from the dealer Kate Ganz, who bought it from Christie's and sold it to a Canadian at a similar five-figure price in 2007, Kemp says. It is unfortunate, he adds, that the attribution has suffered because a Canadian "forensic art expert", who detected a fingerprint that appeared to match one on another Leonardo, has since been "rather discredited" over a work whose attribution to Jackson Pollock has been disputed.

Marchig lost her initial legal case against Christie's because it was time-barred, or too late under the statute of limitations; she could still pursue legal action because, bizarrely, there are grounds for challenging what happened to the original Italian frame. Kemp says: "Christie's removed it and put it in a German frame. The Italian frame has disappeared."

Christie's declined to comment on the frame, but a spokesman says: "The attribution of the majority of all Old Master paintings and drawings is determined through comprehensive scholarship and science. This work continues to prompt a healthy debate among the world's leading scholars."

Kemp's announcement comes ahead of a National Geographic documentary about scientific analysis of the drawing, to be screened next year. Kemp will also publish his research next year, in the Italian edition of his book on La Principessa.

The debate will no doubt continue.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion