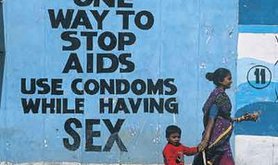

As the HIV and AIDS sector gathers once again at the 19th International AIDS Conference to discuss what they call “the science” it is critical to consider trends at a popular level across Africa which draw people living with HIV away from the technologies and health commodities that we know can enhance their lives. Christian charismatic faith healing- the belief in the healing power of prayer to cure HIV and TB- is a latent yet powerful presence in the lives of many Africans living with HIV and those supporting family members and friends who have the virus.

How and where faith ‘enters’ in HIV and AIDS

It is critical not to conflate all religious engagement with HIV and AIDS and problematic trends in some faith-based responses. However in order to understand the degree of space open for and popularity of Christian faith healing around HIV and TB, it is necessary to appreciate how much ground there is in place for religious engagement around HIV and AIDS in the African region overall.

In the early years of the HIV and AIDS epidemic in Africa, religious organizations began to intervene to provide respite and care for the sick and dying through pastoral care and health services offered in Church-run health centres and hospitals and through Church outreach services. Established and well-funded religious institutions such as the Catholic and Seventh Day Adventist churches were critical in providing services that weak public health systems were not able to provide in many countries. A Gates Foundation-funded research study found that in countries with high HIV prevalence such as Uganda and Zambia, religious entities provide around 30% of health services nation-wide, with even greater coverage in rural areas. As such, they continue to be key actors in delivery of medical care and treatment for people living with HIV.

Views on the implications of faith-based provision of services are mixed among progressive activists and analysts, and also by country context and from service to service given the varied dynamics between church, state and the general population. There are, however, two main concerns from a human rights perspective. The first lies in transferring state responsibility for upholding citizens’ right to health to independent non-state bodies. Analyzing the role of Anti-Retroviral (ARV) provision by Catholic Relief Services (CRS) in Western Uganda, for example, Lesenkamp notes that local government in effect ceded authority to the Catholic Church, which in turn reorganized its catchment area for clients to fit within the boundaries of the diocese. This in part was enabled by under-funding of the local government response, as well as active support for the work of CRS by UNICEF and other donors.

Secondly, faith-based service provision poses a challenge to principles of equality and non-discrimination where religious ideology influences service provision itself. The latter is of particular concern for people who fall outside of what Christian fundamentalist discourse deems as “appropriate sexuality”, including women having sex outside of marriage, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) people and sex workers. Cary Alan Johnson’s analysis of discrimination in HIV and AIDS health service provision for African LGBTI people points out the problematic role that Church-supported services have played given that staff often hold homophobic attitudes and may actively stigmatise LGBTI people coming in for services. Examples include publicly humiliating clients presenting with anal sexually transmitted infections (STIs), service providers giving personal opinions regarding people’s sexual choices, or actively denying services to clients whose preferences they disapprove of. This in turn discourages LGBTI people from seeking further support for their sexual health concerns.

It is harder to hold religious entities providing services to account on human rights standards where they function independently of the state, or even as businesses in their own right. Barriers to access quality services are further exacerbated in contexts where national law criminalises sex work or same-sex practices, which in turn makes it difficult for clients to contest discriminatory treatment within services.

Hopeful cures

Across African countries people seek health information and services from a range of sources. These include biomedical (Western medicine) practitioners as well as traditional healers, and spiritual healing in both Christian and Muslim faiths. Faith healing is a common practice among charismatic Christians in African contexts. For Pentecostal and other charismatic Christians, faith healing is considered one of the gifts of the Holy Spirit that can be received by believers, and as such requires no formal training to deliver.

Mainline Catholic and Protestant churches have had a supportive stance regarding ARVs and science-based treatments for HIV-related illnesses, and are key partners in rolling out biomedical treatment at the local level in many African countries as well as advocating for treatment access. The problematic trend emerging among some Pentecostal and charismatic churches however is support for faith healing to “cure” HIV and opportunistic infections. This includes contesting the efficacy of medicines, and encouraging patients to cease anti-retroviral therapy and sometimes treatment for opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis in order to receive the healing power of faith.

The concern raised by African women’s rights and AIDS activists regarding faith healing is substantiated by a number of public and media queries around faith healing in individual African charismatic churches. A recent example is the influential Nigerian pastor and televangelist T.B. Joshua and his megachurch The Synagogue, Church of All Nations (SCOAN) that has branches in Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa and countries in Europe. SCOAN makes public claims to be able to heal people of HIV and other chronic illnesses. Videos and photographs showing alleged acts of healing people of HIV, including medical certificates to show sero-conversion back to being HIV-negative are available on the SCOAN website and Vimeo video channel and blogs supporting T.B. Joshua’s work. In response to media criticisms around the case of three African women with HIV who died after abandoning ARV treatment, T.B. Joshua made a statement in his church against the claim that his church refutes the efficacy of medicines, saying that “God is the healer. He is the god of nature, and medicine is nature. I and my household, The Synagogue family, use medicine.” And indeed he and other clergy in his church network continue to profess the ability to cure HIV and AIDS through prayer.

T.B. Joshua is a particularly visible figure among many African pastors who make these life-threatening healing claims. It is hard to assess the scale of faith healing given the sheer number of independent Pentecostal and charismatic churches operating in Africa and the fact that not all claim to heal HIV and related illnesses. Anecdotally however, reliance on faith healing is a concern expressed by Africans across the continent who are dealing with the impact of HIV and AIDS in their families. It is important to note that many find value in the spiritual solace and psychological strength that faith healing can provide, and that there are Christian faith healers who may offer spiritual healing as part of supporting people on ARV and TB treatment. What is problematic is where religious or spiritual leaders give directives to refuse or stop taking lifesaving biomedical medication and instead rely on the healing power of faith alone.

While faith healing may be based in a genuine belief in the healing power of Christ, it is also lucrative for those offering it, in as much as people who join their churches also become contributors to the churches’ budget in tithes and other offerings. As such, it is very much part of the new economy of religious response to HIV and AIDS. As a form of private enterprise it is also not directly impacted by changes in the donor-funded faith-based response sector.

On the demand side, the appeal of faith healing needs to be understood in the context of economically marginalised congregations who have limited healthcare options, as well as the tremendous emotional devastation that HIV and AIDS has caused across social classes. In terms of the appeal of faith healing, preachers in Pentecostal and charismatic churches also exert a tremendous amount of both class- and gender-based power over their predominantly female congregations. Paula Akugizibwe, an independent consultant on HIV and AIDS/TB points out, “consider the extent of mind control that goes on in these Churches. People are emptying out their wallets with the hope of God given them a Range Rover, so there is no way that they would not be doing the same with something more abstract like good health”. In a similar vein, Beatrice Were, a prominent Uganda AIDS and women’s rights activist describes a common scene in Pentecostal churches:

“The men speak with so much authority in the ears of a woman who has grown up believing that men should not be questioned… and sometimes the pastors even speak in English and use an interpreter even though they speak “broken English” so that the poor women hears the Pastors speaking English—the intellectual power, the financial power of pastors with a suit that shines, a car… as big as the one room that you sleep in! The pastor is glittering from their hair to their nails—that in itself is intimidating—so you are not supposed to question. If Jesus has said that you are negative who are you to question? You need your miracle to happen, so you will stop taking the ARVs.”

Activist challenges

There are a few examples of African activists using formal accountability mechanisms, including the law, to challenge false claims around HIV and AIDS treatment that violate patient rights. In South Africa, the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) pursued litigation against the charismatic church Christ Embassy to remove television advertisements claiming to heal people with TB and living with HIV through prayer. The litigation, begun in 2009, was initiated after TAC encountered the case of a woman with extremely-drug resistant tuberculosis who stopped taking her medicines in order to be healed at Christ Embassy, passed on TB to her children, and eventually died. The case was brought under regulations concerning advertising standards, with a ruling in favour of banning the advertisements in November 2011.

While litigation can set important precedents in regulating unsubstantiated faith healing claims, the precedents do not necessarily correspond with a change in attitudes of believers regarding morals or ideas such as the power of faith to “cure” HIV or TB. Indeed, the legal victory can also be used opportunistically by the churches involved as a demonstration that “sinners”, in the form of activists, organizations or actors in the state, are attempting to undermine God’s work.

A further difficulty with using formal accountability mechanisms to sanction the actions of faith groups is the sheer diversity of churches involved. Unlike mainline Catholic and Protestant churches, Pentecostal and charismatic churches are not governed by a central mechanism or orthodoxy, which makes regulating messages around HIV and AIDS delivered in the context of religious services or pastoral care difficult. Action can only be taken on a church-by-church basis unless broader precedents are set in terms of religious engagement in public life.

The cost of inaction

Despite the problematic presence of faith healing discourse at community level, and acknowledging the few attempts to challenge individual churches, there has in fact been little attention paid to faith healing in international dialogues and strategizing on treatment, or indeed in national advocacy around improving responses. A young South African feminist activist working with women living with HIV points out that: “in South Africa, Zambia and Malawi the women that we mobilize with around HIV and AIDS certainly know of many cases of people who have stopped taking their ARVs after being convinced that they can be healed [by Jesus]. Faith healing is not a secret. But people never really know the scale and the consequence or damage that faith healing causes within communities. It’s almost like an accepted mishap.” She went on to link the low level of organized response around faith healing from HIV and AIDS and women’s activists to two factors. The first is a lack of donor interest in supporting work around challenging religious fundamentalisms and activism to question social and political dynamics around HIV and AIDS. The second is the sheer number of competing activist priorities for women living with HIV and AIDS themselves in a context of inadequate support for their work.

Unaddressed and unregulated however, the trend towards faith healing and away from proven treatments for AIDS related illnesses runs the risk of compromising the individual health of people living with HIV—in particular economically marginalized women—while also undermining efforts to expand access to effective treatment for the majority.

This article draws on the author's research paper Not as simple as ABC: Christian fundamentalisms and HIV and AIDS responses in Africa commissioned by the AWID's 'Resisting and Challenging Religious Fundamentalism's Initiative.

This is one of a series of articles that openDemocracy 50.50 is publishing on AIDS, gender and human rights in the run up to, and during, the AIDS 2012 conference in Washington DC, July 22-27.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.