In April 2010, Twitter announced it was donating its entire archive of public tweets to the Library of Congress. Every tweet since Twitter’s inception in 2006 would be preserved. The donation of the archive to the Library of Congress may have been in part a symbolic act, a recognition of the cultural significance of Twitter. Although several important historical moments had already been captured on Twitter when the announcement was made last year (the first tweet from space, for example, Barack Obama’s first tweet as President, or news of Michael Jackson’s death), since then our awareness of the significance of the communication channel has certainly grown.

In April 2010, Twitter announced it was donating its entire archive of public tweets to the Library of Congress. Every tweet since Twitter’s inception in 2006 would be preserved. The donation of the archive to the Library of Congress may have been in part a symbolic act, a recognition of the cultural significance of Twitter. Although several important historical moments had already been captured on Twitter when the announcement was made last year (the first tweet from space, for example, Barack Obama’s first tweet as President, or news of Michael Jackson’s death), since then our awareness of the significance of the communication channel has certainly grown.

That’s led to a flood of inquiries to the Library of Congress about how and when researchers will be able to gain access to the Twitter archive. These research requests were perhaps heightened by some of the changes that Twitter has made to its API and firehose access.

But creating a Twitter archive is a major undertaking for the Library of Congress, and the process isn’t as simple as merely cracking open a file for researchers to peruse. I spoke with Martha Anderson, the head of the library’s National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program (NDIIP), and Leslie Johnston, the manager of the NDIIP’s Technical Architecture Initiatives, about the challenges and opportunities of archiving digital data of this kind.

It’s important to note that the Library of Congress is quite adept with the preservation of digital materials, as it’s been handling these types of projects for more than a decade. The library has been archiving congressional and presidential campaign websites since 2000, for example, and it currently has more than 200 terabytes of web archives. It also has hundreds of terabytes of digitized newspapers, and petabytes of data from other sources, such as film archives and materials from the Folklife Center. So the Twitter archives fall within the purview of these sorts of digital preservation efforts, and in terms of the size of the archive, it is actually not too unwieldy.

Even with a long experience with archiving “born digital” content, Anderson says the Library of Congress “felt pretty brave about taking on Twitter.”

OSCON Data 2011, being held July 25-27 in Portland, Ore., is a gathering for developers who are hands-on, doing the systems work and evolving architectures and tools to manage data. (This event is co-located with OSCON.)

OSCON Data 2011, being held July 25-27 in Portland, Ore., is a gathering for developers who are hands-on, doing the systems work and evolving architectures and tools to manage data. (This event is co-located with OSCON.)

What makes the endeavor challenging, if not the size of the archive, is its composition: billions and billions and billions of tweets. When the donation was announced last year, users were creating about 50 million tweets per day. As of Twitter’s fifth anniversary several months ago, that number has increased to about 140 million tweets per day. The data keeps coming too, and the Library of Congress has access to the Twitter stream via Gnip for both real-time and historical tweet data.

Each tweet is a JSON file, containing an immense amount of metadata in addition to the contents of the tweet itself: date and time, number of followers, account creation date, geodata, and so on. To add another layer of complexity, many tweets contain shortened URLs, and the Library of Congress is in discussions with many of these providers as well as with the Internet Archive and its 301works project to help resolve and map the links.

As it stands, Anderson and Johnston say they won’t be crawling all these external sites and end-points, although Anderson says that in her “grand vision of the future” all of this data — not just from the Library of Congress but from all these different technological and cultural heritage institutions — would be linked. In the meantime, the Library of Congress won’t be creating a catalog of all these tweets and all this data, but they do want to be able to index the material so researchers can effectively search it.

This requires a significant technological undertaking on the part of the library in order to build the infrastructure necessary to handle inquiries, and specifically to handle the sorts of inquiries that researchers are clamoring for. Anderson and Johnston say that a cross-departmental team has been assembled at the library, and they’re actively taking input from researchers to find out exactly what their needs for the material may be. Expectations also need to be set about exactly what the search parameters will be — this is a high-bandwidth, high-computing-power undertaking after all.

The project is still very much under construction, and the team is weighing a number of different open source technologies in order to build out the storage, management and querying of the Twitter archive. While the decision hasn’t been made yet on which tools to use, the library is testing the following in various combinations: Hive, ElasticSearch, Pig, Elephant-bird, HBase, and Hadoop.

A pilot workshop is slated to run this summer with researchers who can help guide the Library of Congress in building out the archive and its accessibility. Anderson and Johnston say they expect an initial offering to be made available in four or five months. But even then, access to the Twitter archive will be restricted to “known researchers” who will need to go through the Library of Congress approval process to gain access to the data. Based on the sheer number of research requests, there are going to be plenty of scholars lined up

to have a closer examination of this important cultural and technological archive.

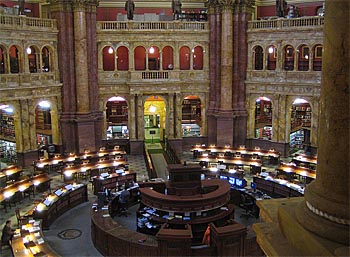

Photo: Library of Congress Reading Room 1 by maveric2003, on Flickr

Related: