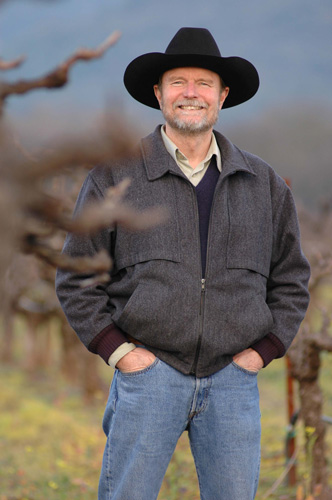

Last Monday I got the opportunity to sit down with famed Zinfandel winemaker Joel Peterson of Ravenswood at The Frog and the Peach in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Obviously I jumped at the chance. At 65, he’s still running and gunning, and while he’s certainly an obvious and effective ambassador for the brand he co-founded and built, he’s still—amazingly—the winemaker-in-chief and also the scout and overseer of dozens of vineyards where Ravenswood sources its grapes.

Last Monday I got the opportunity to sit down with famed Zinfandel winemaker Joel Peterson of Ravenswood at The Frog and the Peach in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Obviously I jumped at the chance. At 65, he’s still running and gunning, and while he’s certainly an obvious and effective ambassador for the brand he co-founded and built, he’s still—amazingly—the winemaker-in-chief and also the scout and overseer of dozens of vineyards where Ravenswood sources its grapes.

Peterson founded Ravenswood in 1976 with a guy named Reed Foster, whom he met at an East Bay (San Francisco) wine tasting group. They had 4,000 bucks; there was no physical winery, and there were no dedicated vineyards; really there was just an idea of making European-style wines with a decidedly non-European-style grape. Zin was really not in. Or so you might think. More about that later.

Peterson was first and foremost a scientist, and while he kept his moveable winery going for 15 years, he also kept his day job in the clinical lab at Sonoma Valley Hospital. He spent his off-time visiting and striking deals with vineyard owners, building the business, bringing in a little money from investors and staunchly resisting the push to make a White Zinfandel to capitalize on the popularity and profit of that sweet pink stuff. Thus was born Peterson’s motto: “No Wimpy Wines.” Instead, he and Foster decided to grow, blend and label a Zinfandel wine that you might say “typified” the grape at a very affordable price, the Vintner’s Blend.

Ravenswood grew from a scant few hundred cases to a few thousand, until it was a sizeable winery by any standard. Eventually it went public, in 1999, and a mere two years later was bought by Constellation Brands, which today is the world’s largest wine and spirits company.

When he was bought out, Peterson took home some serious cash, and he could have just taken the money and run, which is what a lot of successful winemakers do, some by choice, others not. But he’s chosen to stay on and “run the show” instead, and the Constellation folks seem genuinely grateful to have him around.

You might make the argument that Ravenswood is now a mass-market brand that doesn’t have a lot of distinguishing character, and we talked about that. I look at this issue very differently. The reach and distribution of Constellation, and the attractive price of the Vintner’s Blend introduces a lot more people to the Zinfandel grape than might otherwise try it. And that market power allows Joel Peterson to keep making his county appellation and single vineyard wines, his top of the line. Those two are certainly not mass-market products.

A little over a year ago, Peterson was inducted into the Vintner’s Hall of Fame, along with August Sebastiani of Sebastiani Winery and Bob Trinchero, owner of Sutter Home Winery and Trinchero Napa Valley. He joins others you also surely know—Robert Mondavi, and Ernest and Julio Gallo—and some you may not know but who have markedly shaped American winemaking, such as John Daniel Jr., Gustave Niebaum and André Tchelistcheff. The Vintner’s Hall is like the Oscar of the wine world, and while Peterson downplayed this recognition, I suspect he’s truly awed and really quite thrilled to join such a group. And I was a bit thrilled to learn during dinner that he and his partner used to sit and entertain—and surely were entertained by—Mr. Tchelistcheff of Napa’s Beaulieu winery, a guy who, for us wine aficionados and historians, is more than a legend.

As our dinner began, Peterson told me that wine has always been a family affair, and one of his earliest stories—probably not from memory since that would have made him about four years old—was a bottle of Chateauneuf-du-Pape at the Thanksgiving table in 1951. After both his parents became enamored with European wines, his father founded a wine tasting club, and his mother became a recipe tester and a confidante of Alice Waters, the famed Chef-owner of Chez Panisse in Berkeley. She was also, remarkably, a nuclear chemist who worked on the Manhattan project. Maybe what all of this adds up to is that Joel grew up with both a love of wine and science, and the discipline that it takes to taste wines and commit them to memory.

As our dinner began, Peterson told me that wine has always been a family affair, and one of his earliest stories—probably not from memory since that would have made him about four years old—was a bottle of Chateauneuf-du-Pape at the Thanksgiving table in 1951. After both his parents became enamored with European wines, his father founded a wine tasting club, and his mother became a recipe tester and a confidante of Alice Waters, the famed Chef-owner of Chez Panisse in Berkeley. She was also, remarkably, a nuclear chemist who worked on the Manhattan project. Maybe what all of this adds up to is that Joel grew up with both a love of wine and science, and the discipline that it takes to taste wines and commit them to memory.

The thing I took away from meeting Joel Peterson is the way he’s been able to focus on harmony to get what and where he wants to go. When he had no money to build a winery or buy a single vineyard, he was content to be a nomadic winemaker and just make deals with vineyard owners and mobile bottlers for years. When his investors wanted to cash out, he could have fought them but instead found a way to keep on doing what he loves while inside a giant commercial enterprise. He doesn’t complain that he’s forced to make hundreds of thousands of cases of a “cheap” varietal wine; instead, he introduces a “journeyman’s” Zin to millions of people every year, strengthens an already powerful brand, and gets the freedom and the funds to create his high-end county appellation line and his prestigious single vineyard wines. Sounds like a pretty smart approach to me.

And here’s an amazing and improbable coincidence that Joel and I discussed, and that he was astonished that I knew. There’s a strip of land in Queens, in New York City along the east River called…Ravenswood. It was never incorporated, but it’s still known by that name today, and there’s even a powerplant by that name operating there, just south of the Roosevelt Island Bridge. That land was acquired in the early 1800s by one Colonel George Gibbs, who just happened to be a horticulturist, and who received the first cuttings of Zinfandel vines in the 1820s from Austria, and eventually sent some to Boston. They eventually found their way to California. So there was a Ravenswood-Zinfandel connection in New York long before there ever was one in California!

During dinner and between tastings of several of his signature wines, I sneaked in a few questions:

Q: You know, I’ve only got a mediocre palate, and I’ve tasted probably a couple thousand wines. Your palate is remarkable, and remarked upon. Are you a super-taster, or just better than the rest of us, or what?

JP: Well, I’m really not any better than anyone else, but I’m probably more experienced. I’ve tasted maybe 10,000 wines, probably a lot more than that. I’ve learned to use my nose and my mouth the way others have learned to use their eyes and ears. And I have the advantage that I started as a kid.

Q: When people think of Ravenswood they invariably think of Zinfandel. What do you want them to think of when they think of the Zinfandel grape and wine?

JP: Well it’s interesting. In 1983 I made the first Vintner’s blend, which is relatively inexpensive. But of course we do more than Vintner’s, so while that’s been so popular and successful, I make the single vineyards’ blends. I like to consider myself a really good red wine maker, not merely a Zinfandel winemaker. You know, I grew up drinking wines from a lot of places; I know great vineyards and so I try to make wines that are special for place. And one thing about me, I like the challenge of making good wine from bad vintages. And I do love Zin…it’s right that I’ve been pigeonholed as a Zin guy, but I have made some of the most interesting and best Zins around, and I’ve avoided the three deadly sins: too much oak, too much alcohol and too much sugar. I have an image of what wines should be based on when I started drinking as a kid – a stunning balance of acid, tannin, and fruit.

Q: Zinfandel is a Croatian grape with an Italian version grown in Puglia. How would you compare it to Primitivo, especially for an American Audience?

JP: Keep in mind that grapes can test the same genetically but not be the same. Pinot Blanc and Pinot Noir test the same genetically. Puglia is close to Croatia and it appears that Zin went across the Adriatic Sea in the 1700s. In California in our heritage vineyards we’ve planted both Primitivo and Zinfandel in random selections. It turns out Primitivo is smaller and looser clustered and more even ripening. This makes sense, given that Puglia is hot, with sandy soils and you’d need to select for a grape that is climatized for these conditions. Our Zinfandel, because of the way it came to the US, became climatized for New York, Boston and finally California; the clusters are tighter, the berries are bigger, and there’s more uneven ripening. When we made the wine for the sub-units, the Primitivo stands out, it’s fruitier, softer, and it doesn’t have the concentration that you get from the “raisining” that the Zinfandel can have. There is a real difference. You could never produce our Zins from Primitivo.

JP: Keep in mind that grapes can test the same genetically but not be the same. Pinot Blanc and Pinot Noir test the same genetically. Puglia is close to Croatia and it appears that Zin went across the Adriatic Sea in the 1700s. In California in our heritage vineyards we’ve planted both Primitivo and Zinfandel in random selections. It turns out Primitivo is smaller and looser clustered and more even ripening. This makes sense, given that Puglia is hot, with sandy soils and you’d need to select for a grape that is climatized for these conditions. Our Zinfandel, because of the way it came to the US, became climatized for New York, Boston and finally California; the clusters are tighter, the berries are bigger, and there’s more uneven ripening. When we made the wine for the sub-units, the Primitivo stands out, it’s fruitier, softer, and it doesn’t have the concentration that you get from the “raisining” that the Zinfandel can have. There is a real difference. You could never produce our Zins from Primitivo.

Q: A little over a year ago you were elected to the Vintner’s hall of Fame. Not wanting to sound like a local TV anchor, I’d still like to know “how that felt” and what you think your contribution has been.

JP: I don’t work for rewards, but to be recognized…to be put in the company I was put in, well I have no idea why I’m in there. I have gotten to do what I love to do, so if you get to share the same space with Andre Tchelistcheff, Mike Grgich and Randy Graham, it’s pretty stunning. One of the really nice bookends is that people come to the event, and they’re your friends. My son got to stand up and talk. Morgan (his son) talked and when he was done there wasn’t a dry eye in the house. It’s remarkable. Part of being a winemaker isn’t just transforming grapes into wine, it’s pleasing people!

Q: If I’m not mistaken, I’ve hear you say you grew up drinking Bordeaux blends. How did you go from there to Zinfandel?

JP: I was actually in love with Bordeaux and I wanted to produce a Bordeaux blend before Bordeaux blends were popular. I wanted a vineyard that was planted with Bordeaux blends, but Cabernet Franc (one of the five Bordeaux grapes) pretty much didn’t exist back then, and Cabernet Sauvignon was very expensive. I had a conversation with a colleague who told me that Zinfandel is “the Bordeaux of California.” (Zin) Crop levels then were very low, but Zin nonetheless became my Cabernet…it had what I call “parallel typicity,” and in fact it had actually been called “Claret” by some California wine people. So I’m making Zin in a more Bordeaux style – with perfume, fruit, structure, emblematic of European wines. The best feedback I get is from Europeans…that my wines are not overripe, not sweet, and not what they expect—in a good way—feedback from the very people from whom I learned to make wine. So I really haven’t gone far from what I set out to do. And I also did something with the Pickberry (Peterson’s equivalent of a Bordeaux blend) that that I set out to do…and in California. I found a way to be authentic without being ersatz.

Q: How did life change with Constellation?

JP: Well, for sure they wanted to grow Vintner’s blend, and they did. Before the sale, nobody really knew how big we were—at the time 450,000 cases. People tend to make judgments about sizes of wineries. Constellation had distribution power that we didn’t have, and Vintner’s Blend is now, I think the most consumed Zin the world over. Constellation is like most large organizations, it runs in talent sets. So there are are talent sets for hospitality, talent sets for visitor centers, talent sets for sales. They don’t operate the same way that a winery does. My challenge is to get these talent sets to function as a unit for the winery. Part of me would still like to be a 7,000 case winery again, but I’m certainly not unhappy. I started out as a sole proprietorship and went public, so I understand public companies. You have to sell wine if you want to stay in business. Constellation’s motivation is to make good wine and sell it, and look at the brands they have – Ravenswood, Mondavi, Estancia, Franciscan, and Simi. They are doing it right.

Here are the wines we tasted:

Dickerson Zinfandel 2008: 100% Zin, lots of red Raspberries with some mint and cedar. Lots of nose on this wine. Picked pretty early in the season, and only 755 cases made.

Dickerson Zinfandel 2008: 100% Zin, lots of red Raspberries with some mint and cedar. Lots of nose on this wine. Picked pretty early in the season, and only 755 cases made.

Belloni Zinfandel 2008: 78% Zin, and the rest an admixture of Petite Sirah, Carignane (one of my favorite grapes) and Alicante Bouschet, a grape I bet you never heard of. This is very berry and a little jammy, yet clean and brisk with a nice underpinning of acid to keep it fresh and lively. Picked in the middle of October. Just over 535 cases.

Barricia Zinfandel 2008: 80% Zin and 20% Petite Sirah. From Sonoma Valley, this is a dry-farmed vineyard that produced a noticeably tannic wine. But don’t get me wrong, I liked it, and it has the structure to last a good long time.

Old Hill Zinfandel 2008: Another mélange of 75% Zin and 25% “mixed blacks.” This was a Vineyard belonging to famous Vintner William Hill who believed in so-called “Iberian Varieties” and some of these vines date back to the 1860s. Joel told me there are as many as 13 other grapes in this wine, making it more like a Chateauneuf du Pape than a traditional Zinfandel. Wow.

ICON 2008 actually has only 37% Zin, with 36% Petite Sirah, 24% Carignane and 3% Alicante Bouschet. It’s packaged in a Burgundy bottle, but it really stands out where it counts with dark, dense blackfruit, a dancing violet perfume and a long finish. Fun.

Pickberry 2008 is Joel’s homage to Bordeaux. This one is 58% Merlot and 42% Cabernet Sauvignon only, ‘cause evidently Joel wasn’t satisfied with the Petite Verdot and Malbec that the cool 200 growing season produced.

Recent Comments