Most arguments in favor of net neutrality regulation focus on fairness to the public. Definitions of "net neutrality" often characterize it as a principle that fosters free speech on the Internet. But a new study contends that barring ISPs from favoring certain content providers is more than a good concept—it's also sound economic policy.

"Without net neutrality rules, new technologies could lead to pricing practices that transfer wealth from content providers to ISPs," warns the Institute for Policy Integrity, "a form of price discrimination that would reduce the return on investment for Internet content—meaning website owners, bloggers, newspapers, and businesses would have less incentive to expand their sites and applications."

Such a reallocation of resources would hobble investment in the 'Net overall, concludes Free to Invest: The Economic Benefits of Preserving Net Neutrality (cheat sheet version here).

IPI is a New York University-based think tank that looks closely at environmental issues. But as the group's executive director Michael Livermore told us, the outfit also focuses on what it sees as a missing element in much pro-environmental regulation policy, the use of cost-benefit analysis. Generally, this kind of thinking is used to oppose government intervention on the grounds that some specific regulation actually has more costs than it produces in benefits.

But it doesn't have to be that way. "Americans are willing to support regulation that solves significant failures of the marketplace, and cost-benefit analysis can show where new or strengthened regulations are justified on economic terms," Livermore writes.

So when Consumers Union encouraged IPI to take a look at broadband-related issues, the institute adjusted its work from climate change to the 'Net. Here's what it saw.

Market failure in cyberspace

Free to Invest begins by outlining the 'Net's simultaneous strength and weakness. The big strength, as any Web user knows, is vast amounts of cheap or free content—news, blogs, music, video, games, social networks. It's all out there for "free," in the sense that once you've paid for a device and an ISP subscription, the rest of the ride is gratis.

But, while all these goodies provide billions of dollars in "free value" for the public, "websites are not compensated when their content is repurposed or passed on," the study notes, which means "fewer subscriptions to paid services, fewer direct page views, and a loss of advertising dollars."

As a consequence, "the Internet is more useful to everyone on it, but Internet Service

Providers (ISPs) and content providers are at a disadvantage since they are not compensated for all the information they disseminate," according to the report. "This leads to systematic underinvestment in the Internet: if that income could be accessed, it would encourage investment in infrastructure and content."

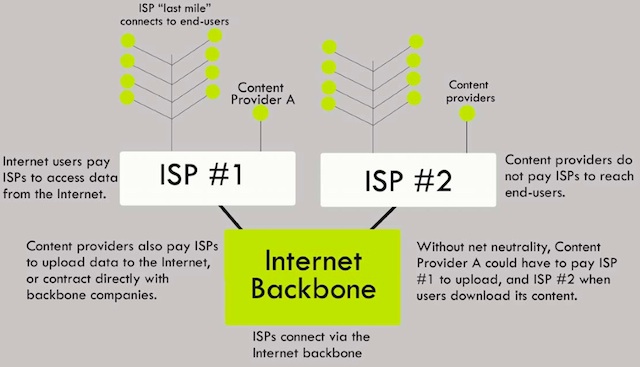

There is a way that the big ISPs could generate additional income. They could do more than just charge content providers to upload their data to the Web. They could tithe them in various ways for priority subscriber access, which is what both AT&T and the cable companies say they want. The telcos and cable call this "value added" or "enhanced delivery" service—but basically it would involve content makers paying the ISPs more money for faster subscriber access.

Free to Invest warns that this kind of marketing would cost the Internet economy overall. Price discrimination "would reduce the return on investment for Internet content—meaning website owners, bloggers, newspapers, and businesses would have less incentive to expand their sites and applications," IPI argues. "Smaller websites might not be able to afford the fees leading them to close up shop. Start-ups might not actually start up because it costs too much or the profits aren’t worth the investment. If too many sites decide it’s just not worth the price of entry, the Internet loses value to the people who use it."

Critics decry the Federal Communications Commission's proposals to bar priority access deals. They call net neutrality "a solution in search of a problem." But, as IPI notes, that's because the Internet in the United States is currently running under de facto net neutrality rules already. The ISPs have voluntarily, albeit reluctantly, refrained from cutting priority access deals with content providers. The FCC's net neutrality proposals would codify many of these voluntary practices into law.

Zero sum transfer

Were the big ISPs allowed to offer priority access tiers, it would represent a siphoning of money from the Internet's content sector to its infrastructure sector. Free to Invest's cost-benefit analysis calls this transfer bad economics. Competition in the Internet content market is much stronger than it is in the market for broadband service, the report contends. In content-land, the situation is constantly changing, "with new product and players emerging at a furious pace—content providers must adapt (and invest in changing and adapting) to keep up with other content providers."

On the other hand, in ISP-land, most consumers have access to two viable high speed providers, at most. "Thus, ISPs do not need to be as vigilant about competition or use their investments to compete with potential new entrants into the market," the paper argues. "Instead, they are free to use their additional revenue to generate proprietary content, invest in other parts of their business, pay dividends to shareholders, or reward managers with bonuses."

And so abandoning net neutrality would transfer money from the most competitive parts of the Internet and actively reinvest it in the least competitive, IPI warns. But the study acknowledges that more needs to be done to boost investment in the 'Net overall, especially to make broadband available to more of the country.

That's why the group favors direct government support. It's hard for the government to subsidize content, which requires making subjective decisions about which kinds of content to help financially. But it's easier to underwrite infrastructure—something the US has been doing for over a century via support to railroads, rural electricity, federal highways, and (most recently) the White House's $7.2 billion broadband stimulus program.

"A policy that encourages content investment through a favorable pricing structure [net neutrality], while directly supporting infrastructure, then, is likely to be the best available option to achieve more efficient levels of investment," the paper concludes.

Of course, while government broadband investment might be easier on a policy level, it's not so easy on a political level. Most observers agree that the amount of federal infrastructure money allocated so far won't get the job done, with one outfit predicting a broadband gap of 40 million households through 2014, even at present levels of public and private investment. And it's unclear whether the Obama administration has any plans for a second big stimulus package. But in our conversation with IPI director Livermore, he seemed guardedly optimistic about future prospects. "The 'Net as we currently know it is only about 15 years old," he pointed out.

Speaking of money, we did ask where IPI gets theirs. The think tank has received project grants from the Hewlett Foundation and the Rockefeller fund, we were told. It's also backed by NYU. As for this net neutrality report, the Institute produced it on its own dime.

reader comments

57