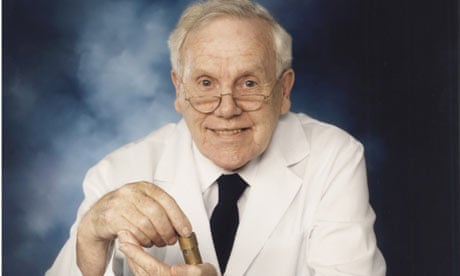

John Wild, who has died at the age of 95, was the father of modern-day ultrasonic scanning, a procedure that has brought immense benefit to millions, including pregnant women and cancer patients. Commencing in the late 1940s, his work anticipated by some 20 years the invention of the other two common scanning procedures – X-ray computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging – and has provided a universally used technique for visualising the soft tissues of the body.

Wild was born in south-east London, the son of an accountant, and grew up in Chiswick. He attended Merchant Taylors' school in the City of London where, at 14, he invented a valve that allowed hot and cold water to flow evenly from bath taps, which he patented. In 1933 he began studying at Downing College, Cambridge, gaining a degree in natural science, and in 1942 he graduated as a bachelor of medicine. During the second world war, he worked as a surgeon at the North Middlesex and other London hospitals, treating casualties from the blitz.

A quintessential angry young man, he soon left the restrictions of postwar Britain. In 1946 he joined the department of surgery at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, where he continued his wartime interest in bowel failure following impact trauma. This led him to look for a non-invasive means for assessing the condition and thickness of the bowel wall.

In Britain he had got to know Donald Sproule, inventor of an echo-testing method for detecting cracks in armour plate, and in Minneapolis he met up with Donald Neale, who was working at the nearby Wold-Chamberlain naval air base, using the same principle as the basis of a radar trainer. In this, the ultrasonic echo signals were reflected back from a similarly scaled-down map of "enemy" territory. Wild was able to smuggle in pieces of dog bowel and later women with breast lumps to replace the "enemy targets".

By the end of the 1950s, Wild and his collaborators had explored the possibilities for using this technique to investigate and scan a wide variety of clinical problems and had published a considerable series of journal papers describing their work. His work was largely ignored, particularly by his American colleagues.

However, a few researchers picked up on it, notably Val Mayneord, professor of physics at the Royal Marsden hospital in London, who saw in it possibilities for accessing the brain. Mayneord's interest, in turn, attracted the attention of Ian Donald, newly appointed professor of mid-wifery at Glasgow, who recognised the potential of ultrasound in obstetrics and gynaecology and went on, with the help of his engineering colleague Tom Brown, to develop what became the world's first commercial ultrasonic scanner – and the first scanner of any kind. This began the scanner revolution in medicine, largely the consequence of Wild's imagination and initiative.

Wild was not alone, but his approach – recording, displaying and making quantitative use of the greatest possible range of tissue echoes – eventually became universal practice.

In 1953 he founded a research unit at St Barnabas hospital, Minneapolis, where he worked until 1960, then became director of the research department at the Minnesota Foundation, St Paul. His funding for echographic cancer detection, which came from the US National Cancer Institute, was being administered by the foundation, with which Wild had strenuous arguments. It responded by stopping his grant and locking him out of his laboratory in 1963.

They had misjudged their man. He took them to court and, in 1972, after years of litigation, a sympathetic jury awarded him $16m punitive damages, later reduced on appeal, on the grounds of defamation and wrongful interruption of the course of cancer research.

Shortly after that, Wild appeared at my front door wearing what seemed to me a very opulent overcoat. When I suggested that this might have been bought out of his winnings, I was smartly put in my place. "This coat? Salvation Army, $10." He had his priorities right. Ironically, the same National Cancer Institute, a year after the trial, had to invite to Washington myself and two Royal Marsden colleagues to explain how ultrasound might detect cancer. When Betty Ford, the wife of the then president, Gerald Ford, was diagnosed with breast cancer in the 1970s, there was nowhere closer than London where she could be scanned for possible secondary growths. Meanwhile, Wild worked as director of the Medico-Technological Research Institute in Minneapolis until 1999.

He once wrote of himself: "I think I must have come into this world with a propensity for making chaos out of order, since I always seem to be upsetting those concerned with maintaining conventional levels of orderliness and humbleness. In my ultrasonic work I have met many people who did not believe the evidence of their own eyes, even when the miracles of pulse-echo ultrasound were demonstrated to them." Maybe this had something to do with the failure, in 1985, of his nomination for a Nobel prize. Some consolation came in 1991 with his award of the Japan prize.

He is survived by his wife, Valerie, their daughter Ellen, and his two sons from a former marriage, Douglas and John, and three granddaughters.