Theresa Dolata had her first suicidal thought at age 5, was hospitalized for mental illness at age 14, and tried to decapitate herself with a sword — "as a sacrifice to God," she says — at age 31. Yet Dolata, now 39, considers herself fortunate.

In 2005, she discovered Vail Place, a Minneapolis nonprofit that helped her find a job, affordable housing and proper medication for her condition: bipolar obsessive compulsive disorder. "I would be on the streets, dead or in a mental hospital were it not for the personal care I've received here," Dolata said.

The state of Minnesota is about to undertake an ambitious effort to duplicate that experience on a large scale for thousands of other individuals who live with potentially disabling conditions, from severe mental illness and traumatic brain injuries to neurological disorders like Asperger syndrome.

Lt. Gov. Yvonne Prettner Solon will unveil a detailed plan Thursday designed to end the unnecessary segregation of people with disabilities by dramatically expanding Minnesota's range of community and home-based treatment options. Crafted by eight state agencies, the plan calls for transitioning thousands of people housed in state-run mental hospitals, nursing homes and other institutions to settings, such as Vail Place, that are less restrictive and more focused on integrating them into the community.

The wide-ranging proposal, developed in part because of a federal lawsuit, would accelerate the controversial deinstitutionalization of mentally ill and disabled persons that began in Minnesota in the 1970s, while altering the way state agencies deliver care for vulnerable populations.

"It's ambitious, but we believe it's the right thing to do," said Solon, who is chairwoman of the committee that drafted the plan. "We really and truly have made an effort to walk in the shoes of the person with disabilities, and to provide services that they feel are the best for them."

Among its recommendations, the 131-page plan calls for increasing the state's stock of affordable housing for people with disabilities by 10 percent a year and dramatically reducing unnecessary hospitalizations at the Anoka-Metro Regional Treatment Center, where a large share of patients could be discharged if there were suitable alternatives. The plan also calls for a reduction in the controversial use of restraint and seclusion in state-run psychiatric institutions — a form of segregation that many disability rights advocates consider unnecessary and inhumane.

Years in the making

Disability advocates lauded many of the report's recommendations, but many were left asking: What took so long?

The proposal, which still must be approved by a federal judge, comes 14 years after the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a landmark ruling, Olmstead v. L.C., which said that segregating individuals with disabilities can be discriminatory. Disability rights advocates have compared the ruling to Brown vs. Board of Education, the 1954 case that banned segregation in public schools.

Twenty-nine other states have unveiled similar proposals, known as Olmstead plans, for reforming the treatment of persons with disabilities.

Many states did not move to adopt an Olmstead plan until they were sued, and Minnesota is no exception.

In 2009, the families of three adults with developmental disabilities filed a lawsuit alleging they were improperly handcuffed at a state-run facility in Cambridge, Minn. A 2008 report by the state's ombudsman for mental health and developmental disabilities found the state facility routinely put residents in metal hand and ankle restraints to punish them — and not just for safety reasons as required by law.

As part of a settlement in that case, the state agreed to produce an Olmstead Plan for improving treatment of people with disabilities.

The state had already taken significant steps toward deinstitutionalizing patients; in 1960, there were more than 16,000 patients in state hospitals, compared with fewer than 2,000 today.

But state officials recognized that the job was unfinished, and the improper use of restraint and seclusion has remained a problem at state-run facilities. Last year, the Minnesota Department of Human Services fined the Minnesota Security Hospital, a state psychiatric facility in St. Peter, for placing a resident in seclusion without a mattress for more than two hours and without any clothing for about an hour. In another case, investigators found that staff at the facility took a patient's mattress away, leaving the patient to sleep on concrete for 25 nights.

'Culture change'

The Olmstead plan calls for a statewide effort to "increase positive practices and eliminate use of restraint or seclusion" by July 1, 2014, as well as a common reporting system for the emergency use of restraints.

"Implementation of this vision will require a culture change … reinforcing positive skills and practices and replacing practices which may cause physical, emotional or psychological pain or distress," the report states.

It remains to be seen how the plan will actually take effect. Many of the proposals, such as increasing the stock of affordable housing, will be expensive. The drafting committee is still working on an overall cost estimate. Solon said officials are also considering the creation of a "permanent office" for holding state agencies accountable for fulfilling the plan.

Today, Dolata runs her own personal-care attendant business.

"I would probably not be here today to talk to you without safe and affordable housing and without meaningful things to do," Dolata said. "After all, what else is there to live for?

Chris Serres • 612-673-4308

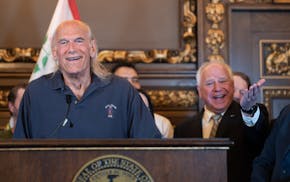

Former Gov. Jesse Ventura boasts he could beat unpopular Trump or Biden if he ran for president

Dave Kleis says he won't run for sixth term as St. Cloud mayor

Newspaper boxes repurposed as 'Save a Life' naloxone dispensaries

St. Cloud house vies for Ugliest House in America